Introduction

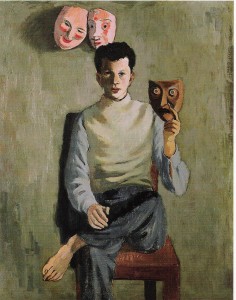

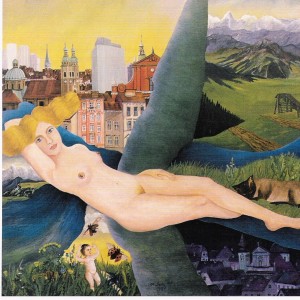

Maksim Sedej yr.: Sunday afternoon in small town under Alps mountains

Oil on canvas, 120×120 cm, 1987

Dr. Dušan Pirjevec was among the first in the contemporary Slovenian cultural space to ask questions about God in the work of art. He did this in his extraordinary essay on the Brothers Karamazov. Pirjevec ends his essay with the following sentence: »The foundation is poetry which is not merely recording reality and does not refer to anything outside itself, but is instead a self-presentation of being in the work of art that begins to emit its own mysterious glow which we can call god.« This sentence which otherwise concludes his thoughts about the basis of the novel or, in other words, the destruction which is revealed in the foundation of the novel and which in contemporary Europe was established by F.M. Dostoevsky. It is as relevant and mysterious today as it was in the time when it was written. Dr.Taras Kermauner no longer poses questions about God and no longer looks for answers to such questions but instead proposes that the divine comes from the same source as the work of art. The examination of the difference between these two authors is very important for the precise understanding of the basic ideas of the discussed text particularly since Kermauner didn’t clarify the divine in his original concept. For example, it is possible to perceive the divine as multi-Iayered, like the Holy Ghost, or conversely, as the singular vision of the mystic. If we want to understand God or the divine and not merely experience or feel God or the divine within ourselves or within the individual personality whether on the personal, the planetary, the cosmic or trans-cosmic level, we must first figure out where the rational image or the perception of man, the planet and the universe stops and what kind of scientific relationship we have toward art and transcendence, toward God and the divine, toward the Other.

This is important above all because of the interwoven nature of the rational and the sensual-spiritual experience of art and because of the existence of the divine in the work of art. Both poetic approaches, Dr.Komelj’s and Dr.Kermauner’s, in discussing the work of art, reach back to the very beginning of the European rational and scientific conceptual basis that was articulated by Parmenides. Plato in his work about Parmenides continued the dialogue, or more precisely, the monolog of Parmenides which established the concept of the One, the One which is walled off from the intervention of »common sense« as well as from god and theology. The One is the introduction into abstract human thought. (Hegel, it should be noted, is more inclined to follow Heraclites who proposed a higher total concept of origins and claimed: What is not being is nothing, and also: Everything flows – everything becomes.) Parmenides spoke thus: If in god, we see what is most perfect, his dominion will have no dominion, his knowledge will know nothing of us or anything else that is ours because our powers al so have no dominion over god and our knowledge al so can not know the divine. The gods, for the same reason, cannot be our masters and can not know of our human events, even though they are gods. Dr. Tine Hribar, a Slovenian philosopher, reasons similarly today: »God is immortal and eternal; people are mortal and thus we are subject to two things: survival and striving for freedom.« It is precisely the freedom of human will (choice) and thought that is essential for both of these philosophers.

Nevertheless Parmenides’ concept of the One, in fact, reveals both the duality and the unity of the natural foundation of our universe which, according to our current scientific knowledge, emerged as the remainder of the destruction (annihilation) of matter and anti-matter during the earliest period of its existence. (It should be noted, however, that the story of anti-matter in the depth of the galaxies and the universe is far from clear). Anyone who is familiar with scientific newspeak about the discovery of subatomic particles will soon realize that each particle has its opposite, if it is not itself the carrier of two different aspects, the dualism of the wave-particle combined with the cumulative histories in time-space. Based on the dualism of particles (for example, of photons), Werner Heisenberg in 1927 proposed his own remarkable principal of indeterminacy which is one of the basic contemporary laws and discoveries of modern physics and quantum mechanics. There are countless other examples of such things in the universe. We need only mention certain constituent parts of the macrocosm: black holes (quasars) which already at their birth reveal the death of the galaxy though they al so open up numerous other possible explanations and insights.

Parmenides’ concept of One was alien to definition and border, time and space, to identification with itself and difference from itself, similarity and dissimilarity. It is alien to being and knowledge, the categories of which, however, constitute all attributes. It is something different from all of the above, something different in an absolute sense and not in regard to one or the other relative entities. It is for this reason that Emmanuel Levinas believed that the One remains unrevealed; it remains unrevealed not because every insight is too limited or too unknown to accept its light. It is unrevealed because to make the One known already implies duality which is in keeping with the unity of the One. The One is beyond being not because it would be hidden and thus impossible to conceptualize but because it is something utterly different than being. Hence, the concept of One in Parmenides cannot be deduced from singularity.

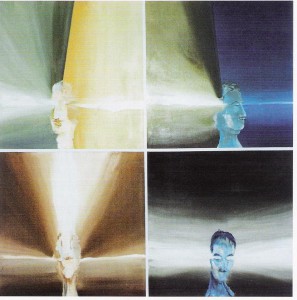

Similarly Dr.Tine Hribar, in his essay The Silence of the Word – The Word of Silence, reveals this duality in his understanding of illumination-light and shadow-darkness. Carl Jung al so discovered the duality of phenomena and events in his essay on synchronicity. It has to do with »the principal of non-causal connection« and the idea that the duality of certain phenomena are independent of space and time. Hegel’s being and nothingness is based on a similar insight. In the visual arts, the duality of the world and creation has been most mysteriously depicted by Hieronimus Bosch in his painting The Seven Mortal Sins. We can al so detect traces of this realization in other Bosch paintings. The great Slovenian painter, Rihard Jakopič, wrote that of all the things in this world the matter and the spirit, the fragments and the whole – there lives the movement between two mighty forces in mutual dependence, in unending exchange and transformation and when these powers will cease then the world will be demolished. Kermauner’s interpretation of the work of art is based on the synthesis and interdependence of science and theological understanding, in the tracing and sensing of the essence of man and the universe. Kermauner has discovered the divine symmetry of the artwork. His experience and reawakening of the Slovenian impressionists is an important contribution towards the evaluation of this Slovenian school for the art-historical field, at least according to certain experts of the discipline.

This book is an effort to understand Komelj’s and Kermauner’s reflections about art, to start us on the way towards our own reflection and perception of the new millenium. It is al so meant as an introduction to the constructive confrontation between contemporary European knowledge and reflections on the Slovenian cultural space. I willl eave it to the reader to decide where the Christian divine of Taras Kermauner belongs. Kermauner’s perception of the divine certainly falls in the general framework of Christianity and it is necessary to distinguish it from the contemporary religious and scientific efforts to replace Christianity and the other great world religions with a number of movements such as the sanctity of life, rational or idealistic monism, cosmic religiousness, new age, new Christianity, etc. both in art and in life. These movements, most of which have emerged in the last forty years (though some as early as the previous century), vary a great deal in their specific origins. They range from the brain-washing of Dr. Cameron in the service of the CIA and Mao’s cultural revolution, from certain segments of the entertainment industry (where I believe a number of commercialized sects belong) to the authentic human striving for meaning and truth outside of the established institutions of faith and society. We must be especially attentive to these movements in the morally emptied space that remains after the legacy of totalitarian ideologies and the suppression of the Catholic Church and Christianity. At least two great Slovenian philosophers have emphasized in their work the scientific aspect of our position in the universe: specifically, Dr. Dušan Pirjevec in his essay on the Brothers Karamazov and Dr. Ivan Urbančič

in his chapter on the position of the earth in his book Zarathustra’s Tradition 1. These two approaches gave me the courage to consult the stars while reflecting on Kermauner’s concept of the divine. And I mean this literally.

ln 1955, the astronomer Sir Fred Hoyle wrote in his book Frontiers of Astronomy: »The universe is everything: animate and inanimate things; the atoms and the galaxy; if the spiritual exists, then the material and the spiritual both; if heaven exists, then heaven and hell both; because by its very nature, the universe is everything there is.« Fred Hoyle’s ideas about the universal nature of the universe, the »eternal balance«, remain an important part of scientific knowledge and thinking about the universe though astronomers today, at least most of them, are inclined to favor a different explanation: that is, the Big Bang theory. Stephen Hawking asks similar questions: if it is true that the universe is whole and inclusive and has neither borders nor edges, that it has neither beginning nor end, that it simply is, what then can be said of its creator?

I do not claim that these reflections are a scientific analysis of the structure of the universe. Rather, they offer a reflection on the condition of science put forward by scientists writing in a popular language and then applying their ideas to fundamental questions about the meaning of the universe and human knowledge. This is a situation when the scientist operates or reflects on a completely different level of knowledge; let’s say on the philosophical or poetic level. Yet almost all contemporary theories about the emergence and the nature of the universe inevitably include the indisputable fact that the universe is expanding and that it is curved. And here we encounter our first difficulty in thinking about the divine. According to the scientific understanding of both the universe and God, there must be a limit, a border that is being established by the ever expanding universe. This border, of course, is not a finite or spatial limitation. In fact, it is very difficult to even explain or define it at all. It would probably be simplest to define it as a time limit, the time limit of the universe which, of course, is not in keeping with our concept of the infinity and eternity of God unless we opine that God exists outside of the universe and it is the Holy Ghost that shines into the universe. In order to make this limit more evident or visible, it is necessary to understand how scientists see the universe and its structure: its »fiat«.

Right at the outset, we must drew attention to a reservation made by Stephen Hawking which tends to be rather uninspiring to astrophysicists. Stephen Hawking believes that, because of the relativity of time, our knowledge of the history of the universe is only one of many possible interpretations of its existence. Whatever we may say today, it is possible that in twenty years, we will discover another version of the true mystery of the emergence of the universe.

This first dilemma which divides scientists is the question of whether the universe is made of a finite or an infinite quantity of matter. This is not such a simple thing since we do know that today’s universe – at least according to the claims of most astrophysicists – contains only about one-milionth of the matter that remained after the destruction of matter and anti-matter that is known as the Big Bang. In the opinion of many astrophysicists, the universe, which took shape from nothing, is composed of a finite quantity of matter. This dilemma, in terms of the contemplation of the divine, has significant consequences. When the Abbe Lamaitre explained his theory of the Big Bang occurring in nothingness, the Holy See accepted it as early as 1951. The other possibility which explains the Big Bang as the origin of the universe, is called the »Cosmic Egg« and contends that the universe is made up an infinite quantity of matter. What’s interesting in these theories is that the »Cosmic Egg« is constantly shrinking. Its proponents believe that the »Cosmic Egg« was once the size of the solar system and then it shrunk to the size of the head of a pin, then to the size of an atom and recently to inconceivably small dimensions – so-called »super-strings« – more than a trillion times smaller than the atom. The prevailing theory, however, about the beginning of the universe is certainly the Big Bang theory. Nowadays, this theory is generally known and it no longer necessary to explain it. Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking demonstrated the singularity of the Big Bang in 1970. Another peculiar aspect of the universe is as follows: that in order to know the future of it we must look back to the past. Stephen Hawking contends that chaos is growing at the same temporal rate as the universe is expanding. Therefore, in order to live intelligently, we must follow the thermo-dynamic temporal arrow. Steven Weinberg believes that the universe is essentially belligerent and that today’s universe developed from an early condition that is indescribably alien to us. Our destruction awaits us either in the form of eternal coldness or unbearable heat. This is why Steven Weinberg writes that the more understandable the universe seems to us, the more inconceivable it actually is. People, of course, aren’t satisfied with this so they create fairy tales about gods and giants or they limit their thoughts to solving quotidian problems. Striving to understand the universe is one of the rare things that elevates human life above the level of buffoons and lends it a touch of the tragic sublime.

According to scientific findings, the universe has its origins and its creations in a hellishly hot energy which, during the Big Bang, exploded and became partially transformed into matter. The universe al so has its own particular development (expanding and perhaps al so retracting) and its death. Looked at in this way, the universe has a human image. Birth, existence and, at the end, death; equal measures of hellish chaos and destruction and of goodness, love, creativity and spirit through which the divine shines.

ln order to obtain a more complete picture of the universe, the ideas of Steven Weinberg are al so important. He believes that it is possible that what we see of the universe – everything from time to core synthesis – is nothing more than a homogenous and isotropic sphere which in turn is located within a larger, non-homogenous, non-isotropic universe. Weinberg’s thoughts pave the way to cosmological-theological theories that each universe is a constituent part of some larger universe, that the smaller resides within the larger. Carl Sagan was extremely enthusiastic about such a conceptualization of the universe. According to these theories, the universe is in God. The only pity is that it will probably never be possible to prove such a theory. The genesis of the existing universe that we see and that some scientists have even weighed can be seen as merely a number that helps us to better understand the whole universe. Our universe is isotropic and develops and expands (or curves) in accordance with certain specific laws. It could even be said that the message of the development of the universe (its inclination) functions in accordance with its own veiled and mysterious plan. Albert Einstein who attempted to place these laws in a unified theory of physics al so advocated this possibility. The great painter, Marc Chagall, picturesquely described in one interview the desire for a rational knowledge of the divine: he said that Einstein died a sad man because he had succeeded in discovering and understanding the structure of the universe.

Nothing that happens in the universe is accidental. »It is a great stage on which the universe acts in its play. It just so happens that the twins of chance and accident al so share a small role.« With these words, Sir Fred Hoyle affirms this and one is inclined to believe him despite the elegant errors in his theory about the »constant« universe. Heisenberg and the majority of other astrophysicists believe that the future is indeterminate and unpredictable, dependent on chance and that the universe will never allow man to fully explain it, to fully understand its logic. I would like to make the observation at this point that indeterminacy (or what philosophers would call skepticism) leaves the universe open in all directions and allows for the development of knowledge that is different from the completely ordered and predestined universe. Between indeterminacy and causality, it is possible that the universe is Inclined in a certain sense toward a very specific meaning in material and spiritual development. Yet perhaps this Inclination of the universe is complemented or completed by the claim of many scientists that God is in the universe (for some, Nature) and that He likes to throw the dice, to gamble, now and again.

It has been proved that the first primal explosion was slightly uneven and that that is what made the emergence of the galaxy possible. Primary matter was mostly hydrogen and helium. The stars emerged from clouds of these elements and the galaxy was created. It must be emphasized that this astrological finding which has been expressed countless times in countless variations is the easiest way to understand life and the growth of the spiritual Universe. Astronomists make a distinction between two kinds of stars: Type II stars which came into being in the beginning, from the gigantic galactic clouds (and, belonging in this category, are also the stars which make up the glowing atmosphere of the galaxy) and Type I stars which emerged and are still emerging from the remaining gases in the galaxy. The beginning of life and especially of developed life on Type II stars or planets is hardly probable. The same can not be said of Type I stars or planets and their environments. Stars exist in an incredibly wide variety of sizes: if they are larger than the sun, say 1.44 times its size, then they explode. Before they explode, the processes in the nucleus of the star create atoms of other primary elements. These elements, blown apart by the explosion, sooner or later serve to enrich the gaseous clouds from which new stars are born. The clouds which create new stars and planetary systems slowly become enriched enabling in a specific period the development of a Universe and the emergence of conditions for the evolution of developed life forms. It seems that such life emerges at a specific instance during the development of the Universe and that it will probably emerge again when a series of specific circumstances and conditions are right. Man is like any other life form created from atoms which have emerged during the nuclear processes taking place in the interior of gigantic stars. Even Shakespeare thought that genius is a starry atom. I don’t know if I have been convincing enough; my purpose is to develop the idea that everything happens in the universe and everything evolves in accordance with the mysterious evolutionary plan (Inclination) of the universe. That is the way galaxies and stars are born, the way developed life is born, love and finally even the knowledge which is known as God. Stephen Hawking believed that God sometimes gambles, that God sometimes throws the dice to see what will come up. With this claim, he takes Werner Heisenberg’s principal of indeterminacy and moves it closer to the limits to which the universe allows man to recognize its structure and meaning.

Yet this should not serve as an inducement to repeat the error, made in another time and with other means, of believing in perfect knowledge or complete understanding of the universe, of believing in some kind of new inclusive Aristotelian system or the final order or disorder of the nature of the universe. The consequences of such an error are well-known from history. This sort of perfect system of divine knowledge of the universe was, for example, put forward by the Catholic Church. Yet the overlapping of faith and secular errors about the perfect knowledge of the universe was forcefully ripped asunder by Gallileo (reviving the ideas of Copernicus and Montanus that the earth rotates around the sun) and by Descartes who articulated the philosophical rationale: I think; therefore, I am. The revelation of God, Christ and the Bible are the legacy of ancient humanity. They are the truth and the beauty and it is not possible to ever completely and rationally explain or understand them. They are transparent and can only be reached with love. For this reason, efforts at social explanations of Christianity (for example, Fromm’s dogma about Christ), psychological analysis (for example, Jung’s Immitatio Christi), historical interpretations of religion, the denial of faith and Christianity in favor of materialism and such, are simply efforts to rationally explain the divine, Poesis, on the level of current scientific truth s or politics. That could also be said of some arbitrary interpretations of the Bible which were given freely by individuals at the very beginning of Christianity. I need only mention Kerint and his vision of the end of the world. George Leclerc and his work Teachings about the Earth, already in the eighteenth century, settled the account with the traditions of Moses’s message about creation and thus replaced Moses in the mysterious symbolism and Poesis of Christianity, in faith. Martin Heidegger in his extraordinary essay about the origin of art analyzed a painting of peasant’s shoes by Vincent Van Gogh. He conducted a detailed analysis of the painting from a number of different viewpoints historical, sociological, social, aesthetic, etc. Following all this analysis, he wrote that he had still said absolutely nothing about the origin of art or about the art of Van Gogh’s picture. Scientific analyses of faith are similar. Heidegger believes that the origin of art can be found in the origin of humanity. The same could be said about faith or about the divine. Man can discover the presence of God in himself, in his relationships with others, in his surroundings and reality, with love and forgiveness, with repentance and mercy. The conscience is that which transcends mere survival and the maintenance of the individual at any cost. Questions about the origins of the conscience present to science the same kind of unanswerable and therefore mysterious inquiry. In today’s scientific times, it almost seems as if the conscience is a bothersome element, more mystical than real. Modern times demand different standards of life; man should be liberated from his own conscience and from God. Money and power are the standards of civilization dominated by science. The divine is merely the multi-Iayered knowledge of human intuition, faith and self-awareness. Science today makes a distinction between the secular concept of the divine and the secular rational understanding of the universe and thus puts a contextual frame within which the questions of humanity are answered: Who is man? Where does he come from? Where is he going?

But the divine cannot be captured by such temporal and spatial limits regardless of the fact that what is humanly understood as limitless and eternal actually refers to the transitory though infinite condition of the universe as it expands (curves). This process of expansion ranges from being as small as the head of pin – as Trinh Xuan Thuan argued when the distinction between time and space did not exist – to the vast expanses that are being continuously created by the universe. God and the divine are creatively and actively present in these events though they are not, by their very nature, temporally or spatially limited and hence exist trans-cosmically. This is not to say that God and the divine are located in some unknown distance, in some kind of heavenly eternity and endlessness. To the contrary, the worldly presence of God and the divine is precisely what defines God as transcosmic. This attribute – this worldliness – is today known under many different names. In other words, many names identify the same entity from belief in God and the experience and acceptance of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross to the presence of the divine and God’s way.

This presence represents the key existential question. God is absolutely Cosmic and Transcosmic. And no one can claim or possess what is trans-cosmic. Man’s liberty is only possible once he assimilates this presence and accepts the divine as his own being. Only in this case can man fully liberate his thoughts and become aware of his role in the world.

This is why reservations about the Gods or about God, whether they are penned by Hribar or Parmenides, are outside of the comprehensive structure of the universe even though they refer to the essence of the problem: to liberate human will (choice) and thought. The hidden intention of these reservations has played an important role in the modern era: they have attempted to remove God and the divine not only from free thought and will but al so from their presence in the world, from the consciousness. This kind of reasoning could have – indeed it has had – horrible consequences. The various totalitarian systems and societies of mere survival are parallel products of scientific development and its consequences. Such a mentality does not require any commitment from man and ultimately leads in the direction of nothingness itself. This, however, stands in contradiction to the human responsibility for the planet – and perhaps even for the entire universe – which was the destiny Adam created for man when he made the distinction between Good and Evil. Our universe is isotropic which is to say that it operates according to a certain set of laws that enable the continuity of its development or expansion (curving). On the one hand, there is the absolute zero degree of heat at minus 273 degrees Celsius, light and its finite speed, the spinning of the electron in the atom and so on and so forth. On the other hand, there are the dual properties of one and the same thing, of the subatomic particle, for example, and the subsequent unpredictability of the final outcome. What is important is to understand these laws as limitations and borders that enable the existence of the universe as it is. I would be no more out in left field than the scientist who claims that he takes the pulse of chefeids as a basis for measuring the approximate distance to the neighboring galaxy, if I were to argue that similar laws and limitations apply to human existence and human essence. A large part of these laws in the spiritual realm can be found in the Christian Gospel. Even today, a denial of God and Jesus Christ will not get us very far. Jesus Christ’s presence on earth undermined, as if in passing, Parmenides’s reservations in his reflections on the Gods. Nevertheless, it is also true that the Athenian sages rejected Saint Paul with scornful laughter when he bore witness to the existence of God and his resurrection during his address on the aeropagus in Athens. But God and God-Man cannot be reduced to the theological or spiritual product of antiquity in a planetary plan (be it conscious or spontaneous) that was meant to harness »the human animal« and give him some higher meaning. The story of God’s incarnation in man’s image and the story of his sacrifice demonstrates the purpose and meaning of humanity, elements that, like the relevance of science and technology, were not yet understood in antiquity. It is said that this tension presents many theologians with almost insurmountable problems. This is certainly the case in some religions.

A part of these laws were in the work of Emmanuel Levinas summed up in the manner of poetical thought. The connection between the Self and the Other is Levinas’ central pillar, representing the immanence of human origins and transcendence.

Assuming that God and the divine exist on both the cosmic and trans-cosmic level, it is necessary to illuminate at least two inextricably interwoven dimensions. These two are time and the claim that God is absolutely transcendental.

Time was defined by modern physics. Maxwell wrote an important chapter on time when he calculated the speed of light. While it may be true that physics often builds upon empty space (filled with Faraday’s electro-dynamic laws), the theory of relativity is doubtlessly the foundation of our rational understanding of time and the nature of the universe. If an astrophysicist were to search for the opposite of relative time in the dual nature of the universe and attempts to do this through a flirtation with the theory of relativity and the relativity of time, it would be prudent for him to take into account the so-called »thought experiment« (Einstein’s Gedankenexperiment). That is, if the astrophysicist is attempting to find something that would replace the now lost unity of time. Let’s say that the replacement would be trans-cosmic time which contains the unique comprehensive character of universe. Several excellent scientists have tackled this problem. Einstein, in his development of a skeptical attitude toward the indeterminacy of quantum mechanics, laid out the foundation for the possibility that certain cosmic truth s are not dependent on the speed of light and are at the same time part of the comprehensive unity of the universe. Individual particles are globally interconnected and function simultaneously regardless of their distance from each other. David Bohm advocated the idea of the universe wherein a part of a general all-encompassing whole is a wave of information that is intertwined with all the others. These transcosmic meditations on time are beautifully linked in Bell’s theorem of interconnected particles as regards distance, that is, as regards the speed of light. This communication was called the infinite whole.

If the spiritual universe exists in the same way as the material universe does, then it is safe to say that spiritual truths and osmosis of the spiritual has no temporal or spatial limitations and is simultaneous in the infinite whole. Man and humanity certainly represent one of the points of contact between the spiritual and the material universe.

ln the depth of insight into and the experience of the spiritual – the divine – certain truth s are contained in connection to the entirety of creation, that is, to the mysterious infinite whole. Love, faith and poetry are, in this context, very significant. The trans-cosmic scientific mind is increasingly understood as an irreplaceable part of this mysterious whole. It is precisely a sophisticated mind and spirit that creates a kind of connection with the cosmic inclination, that leads man on the path into the mysterious depths of the infinite whole.

Many questions and concepts about time and space will be solved by the further explorations of Black Holes. Perhaps all of creation is, in fact, entirely different and operates according to a completely different set of laws. In certain aspects, for example in singularity, time doesn’t exist. Saint Augustus already believed that to be true. He claimed that before the universe existed, time also did not exist. Eternity without time is a wholly different concept than how we currently conceive of it. Indeed, what is ephemeral and what is eternal, as we understand it now, can only exist within our concept of time. Kant’s antinomies, too, open up at least two different problems about the universe and time. In contrast, Heidegger posed the same question thus: a philosopher (who is not abeliever) will understand time out of time itself (for instance, from ‘dei’). What has the appearance of eternity turns out to be only a derivative of temporal being.

Moreover in order to rationally understand time, the following dilemma, which is consistent with the duality of universe, is also relevant: the universe emerged out of primal nothingness yet contains everything, including primal nothingness itself and so it is nothingness by its very nature. Sir Fred Hoyle believe this to be true. That is, that everything that is or has been created exists in the infinity and emptiness of primal nothingness, in the temporally and spatially expanding (curving) of the universe. This gives meaning to nothingness despite the infinite nature of the universe.

According to the opinion of many astrophysicists, the universe will in any event sooner or later disperse into itself (perhaps into primal nothingness) or will collapse into itself or burn (again into primal nothingness). This comes very close to Heraclites and numerous later philosophers who contemplated eternal recurrence. Primal nothingness is the illusory (real) duality of the infinity of the divine. In such primal nothingness, there is room for an infinite number of infinite universes. The temptation to replace primal nothingness with God and to locate it in the foundation of everything that exists, remains great for many philosophers and scientists. This is particularly the case because two levels are intertwined here, scientific and philosophical, wherein nothingness cancels out infinity but not vice versa. Instead of infinity or eternity, nothingness is posited as the original scene of creation. Because it is possible to declare the duality of God-Nothing, it is ever more urgent to define the divine as both cosmic and trans-cosmic.

ln his essay, “The Concept of Time”, Martin Heidegger said that time was subject to both the process of mathematics and to homogenization. He further argued that we tend to compress the whole of time into the present alone. The concept of recurrence is, among other things, a matter of conscience. The past as genuine historicism is anything but that which has passed. It is something that is always open for reinterpretation and recurrence. Heidegger believes that Christian faith must itself have a relationship to something that happened in time. We, for instance, hear people talk about time, as in: »the time had come« or »the time was ripe«.

I think that the point to be made here is that faith is present in every moment of time, at least Christian faith is. Believers need not return to something that is past. Though it hasn’t been conceived as such, this is contrary to the ancient Egyptians who believed that memory of and talk about the deceased helps to resuscitate them.

The Bible contains several passages about time as they are connected to Jesus Christ. It is likely that Heidegger had such passages in mind. For example: »My time has not yet come,« (John 2:5); »My Father, the hour has come,« (John 17:1); »The hour is coming and its has arrived,« (John 16:32); »It is finished ,« (John 19:30). Time, in this case, refers to the final moments of Christ’s worldly message to humanity. In the Christian faith, however, this does not represent an event that remains in history. It is the living path of Christian civilization. The path of Christ is the path of the living God as he is present among us. It is not God’s last will or the ceaseless revival of a historical being. Christ said to his apostles: »1 am with you all the days to the very close and consummation of the age.” (Matthew 28:20). Absolutely transcendence- according to John Paul II, one of the most important figures in the modern Catholic Church – refers to religions where the Almighty can be compared to a God as human as Jesus Christ.

There is an alluring trap here. Because whether or not one has good intentions, it is possible to claim absolute transcendence for oneself and then proceed to regulate the world in its name. Where there is no dividing line between good and evil, between the divine and the satanic, there is no love or forgiveness.

The human God, Jesus Christ, is elusive and can only be felt in love. In »love for nothing«. If I may interpret the thoughts of Dušan Pirjevec in my own way, I say that the divine radiates into the human essence and that God illuminates this essence with his mysterious glow.

2. A rational framework of the human and the divine

What is human can be defined in many ways. Because I am trying to frame the question from the standpoint of art, I have decided to define what is human with dreams and with truly exceptional dreams. Descartes dreamed and, in his own dreams, interpreted his dreams; lam interested precisely in the dreamlike interpretation of dreams. Descartes was of the opinion that there was nothing so unusual about the fact that when reading the work of poets – even those who churn out nonsense – we often stumble on to ideas that are more weighty, more sensible and more beautifully expressed than the ideas we find in the writings of philosophers. He made a note of that fact that the seeds of wisdom sown by poets germinate more easily and brightly than the reason of philosophers while writing about the divine nature of passion and the power of imagination. Precisely this type of poetic approach could characterize a good number of Slovenian thinkers and critics. The poetic approach gives birth to another dimension of truth, the poetic dimension which must be juxtaposed against scientific truth. Human brains are made in such a way that they function at five times the capacity when both halves of the brain – rational and sensual – are harmonized at the highest level. If Peter Russell is to be believed, it is only at these times that the brain is working with its full power. Only in this way can man achieve the greatest creative symmetry. The ability to attain such symmetry is a talent granted to only a rare few and, for this reason, such thinkers and critics are even more precious in the Slovenian cultural space. Milček Komelj and Taras Kermauner certainly be long in this category. At this point, I would like to point out an important difference between their individual poetic sensibilities. Both are recognized academics though, in the sphere of poetry per se, it must be said that the work of Komelj (who is al so a poet) radiates with a sort of metaphysical dimension in which one feels a mysticism, a distrust of coincidence that should play an important role in reality. On the other hand, Kermauner explains many things as coincidence and is more of an analyst than a mystic. In his opinions, he comes intuitively closer to Heisenberg and other scientists for whom many events and things – such as the emergence of life or man – are the product of chance, coincidence. This inclination of Kermauner’s, who is exceptionally knowledgeable about the visual arts, arises from his analytical-philosophical nature and can be detected in his discussions of fiction, dramas, philosophy and other genres. It is only when this characteristic comes into contact with the divine, that we discover in Kermauner’s writings an undefinable dimension and, only in such cases, can we sense his entire philosophical concept. For Komelj, who is also an expert in the field of visual arts, the departure point is precisely the mystical-poetic aspect of painting and poetry. I only draw attention to this distinction because, in the framework of this discussion which has as its foundation the “living presence of the other” and “the presence of the divine” in works of art, it will we easier to recognize the assumptions that define both of these authors. In the same spirit, I al so observe – again as it relates to this discussion – that both authors could select any work of art to confirm his own ideas. This is the usual reproof of readers and critics when they read the presentation and analysis of new ideas.

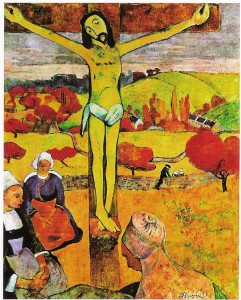

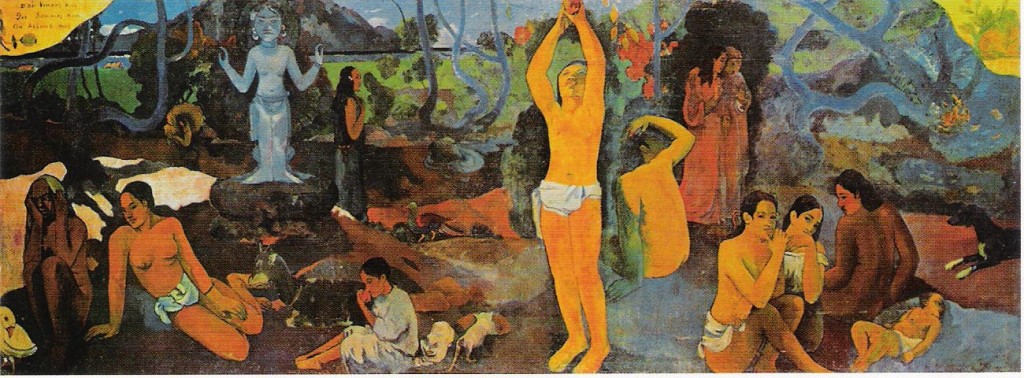

Before we continue the discussion, we must first ask ourselves: Where does man co me from? Who is he? Where is he going? Many have asked these questions in the past. Indeed, Paul Gauguin used precisely these three questions as the title to one of his most mysterious and extraordinary paintings (executed in 1897). Gauguin answers the questions poetically but also with the knowledge of the essence of humanity. He described it in this way: “God does not belong to scholars and logic, but to poets and dreams.«

Paul Gauguin: Where did we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?

Oil on canvas, 139×374,6 cm, 1897

The painting is symbolic. A yellow (sunny) eternity is depicted above a blue sky and primal nature. The yellow light illuminates the few people in the scene. In the foreground stands a glowingly lit male form (outlined in gold). He lifts his hands – which hold an apple (of knowledge) – as if in prayer. He stands in such a way that we presume that he is turning toward the yellow light which we sense at the upper edge of the painting (yellow is the color of God and al so holds special significance for Gauguin who painted a yellow crucifixion scene eight years earlier and called it Yellow Christ). The other figures in the painting are either illuminated by the yellow glow or submerged in the blueness of the sky or the bluish-green of primal nature. It is an image of paradise. Yet this is a human paradise where both love and suffering can reside, childhood and old age, the joy of lovers as well as loneliness, melancholy, grief. The entire scene is imbued with divine blue which is man’s idol and belongs in nature. Birds and animals complete the scene. The message of the painting could be as follows: Adam – man – leaves the primeval natural paradise, comes to understand creation and thanks God for this knowledge. The poetic idea can be sensed in the beauty of life and love and the ephemeral quality of these things as well as in the quiet sadness and harmony which is human nature above which there is something lighter. And man knows this. The blue idol al so warns of the other more elemental side of this idyll. Man belongs to both: to the idol and to God. He is free to decide, to whom and to what degree. The title of the painting is the three questions – Where do we came from? Who are we? Where are we going? – which are hand-written in the yellow picture. Yet the picture is so forceful in its tranquillity and its quiet, in the harmony of its colors and composition, in its melancholy beauty that the perception of the work penetrates deep into a sort of rational explanation, a rational and understanding appeasement. Rihard Jakopič would say that the painting is permeated with truth and purity. Today we know where man and all of life comes from. The source of life is in the center of the stars, in all the fragments thrown out from a gigantic explosion. Yet this is not the whole story of life and of man. The purpose of this book is most certainly not to search for the missing link, some anthropological Adam from millions of years ago in Oldavay Gorge or even farther back in Tanganyika on the Horn of Africa or on the island of Rusing. I would like to find a later Adam. The first Adam would no doubt please the anthropologist, Jacuette Hawks, because our distant predecessors had bodies fashioned like our current human body. They were fashioned with a thumb on their hand which surpasses even the fondest fantasies of scientists and artists. The hand and the thumb became part of the brain. These predecessors of ours developed a creative brain (the neo-cortex) which also oriented them toward the spiritual sphere. This later Adam – maybe the second or third or fourth Adam – which is so much closer to my heart lived maybe 100,000 years ago in what used to be known as Persia. In the valley where he probably lived, he dug a grave and, in it, placed the remains of those that were dear to him. He sprinkled them with red ochre and arranged them in a shriveled human image and then ritually ate the brains which some anthropologists believe is one of the most important discoveries made about humanity – the discovery of the undying soul. This ancient man turned his loved ones toward the sun and sprinkled them with blossoms and closed the grave. Using scientific analysis on the blossoms, experts were able to estimate the age of those buried there. But only someone who has lost those beloved to him, can know the pain and the emptiness felt by the man who lost those whom he loved. Human greatness is doubtless present in this act: that our ancient predecessors understood death and demonstrated respect to their dead. They knew about creation; they sensed the divine and immortal soul.

Adam, then, is the one who stepped out of Nature in which every living being has its place, its possibility to live. The cosmic (asteroids, comets, etc.) and planetary catastrophes (climactic changes, etc.) are also a part of the environment in which we live and survive. The development of the conscience and consciousness is what separates humanity from human animals. By distinguishing between good and evil, Adam seized responsibility for the Planet and the Universe. Man understood Creation; his brains and his love al so held out an offering of immortality and, as the development of contemporary science shows, this is only a question of time. Yet it will be decisive for the Earth and the Universe how this immortal man will develop his love and goodness to the other, to Otherness, to the Sanctity of life, to Creation and the Father of all existing things. It is up to humanity to decide whether our Planet will be paradise or hell. Man is now capable of destroying the Planet and, from its destruction, making hell. Is he also capable of making a paradise here on Earth? ln the Universe?

Life is the great miracle in the universe; death, transformation and passing is the great wisdom of the universe. In the Odyssey, Homer illustrated these two sides of human fate in the meeting between Odysseus and the fallen Trojan heroes. Odysseus told them what great glory they were enjoying and they answered bitterly: “We would much rather live as slaves in the world than as dead heroes.” Weinberger’s statements about humanity are pessimistic: there is nobody who can be successfully frightened with the tragic fate of the universe, nobody who can even begin to comprehend the spiritual universe. Man is unique and yet it is not sufficiently aware of that fact and this holds true regardless of the possibility of other developed life in the universe. The great Russian physicist, Gamov, was for instance convinced that humanity will sooner or late be accepted into a galactic association of intelligent life. Above all, there is no need for panic or depression because we still a have plenty of time. Our galaxy turns around its axis once every 200,000,000 years and every 1,000,000 years it moves a distance equal to its length. It is traveling towards a swarm of galaxies in the Swan at a speed of 20,000 kilometers per second. Answering the scientist in his own language, I surmise that it is more probable that man will create Hoyle’s universe of permanent balance than that it will let the universe freeze or bum. Sir Fred Hoyle may be seen as a prophet some day. At least in terms of the new theologies, even the heavens already show a distinct inclination towards him. The most recent research studies into the vastness of the universe suggest that energy is created by itself in the empty space of the Universe. In terms of Sir Fred Hoyle’s theory of permanent balance, he posited the creation of matter in similar conditions. There are thus indications that the universe reproduces itself.

Moreover, it is not yet clear what and where is the mysterious missing “dark matter” which is thought to be crucial to the future fate of the universe. Perhaps energy is emerging from an anisotropic universe. And energy produces both matter and anti-matter. The concept of the existence of infinitely small particles which are supposed to comprise so-called missing matter is in no way undermined by this theory of energy. If such a theoretical hypothesis can be verified, it will complement the Big Bang theory and at the same time have unimaginable consequences. The comprehension of the universe will indeed shift to the trans-cosmic plane.

On the other hand as regards spirit and thought, Christian metaphysics have already rejected the notion that nothing comes from nothing and has replaced it with the idea of a transition from nothingness into being. Hegel believes that those who advocate the statement – “Nothing is simply nothing,” – are unaware of the fact that by making this assertion they are committing themselves to Eleatic abstract pantheism and to Spinoza’s concept of pantheism. The genetic message of life in the universe is knowable. The quantum leap is al so a part of this message although man himself created his own personality. Man is more or less conscience of his freedom and of his free will to decide. He also knows or at least has a premonition that the conscience is a component of the good, of the godly spark which keeps good slightly ahead of evil in the relationship and conflict between good and evil in the individual and in humanity.

A certain degree of mistrust and caution exists between science and the church – particularly the Catholic Church. This persists despite the fact that church superiors long ago expressed their regret over the fate of Galilleo, Giordano Bruno and other scholars. An important event took place in those times that was a shared turning point for both the Catholic church and for science. The event (and it was probably no mere accident) which had a fatal impact on the development of science and thought and on the Catholic acceptance of a single scientific truth as the only truth, was the conquest of King Philip II. Because of his conquest, it happened that Ptolomeus’ geocentric system and Aristotle’s tidy and unchangeable world view came to correspond beautifully with the beliefs of the Catholic church about the construction of the world. The Spanish king was deeply religious and loyal to the church but he was also strongly influenced by the vision of Hieronymus Bosch. This influence can be discerned in King Philip’s letters to his two sisters. Ludwig Baldass, in his book on the great artist, describes Bosch’s unique vision of the Condition of the world. Bosch created his paintings in accordance with this vision and I think that it is in Bosch’s mystical vision that we must look for the deepest reasons for the artist’s pessimistic view of human nature. Bosch was not the only man of his time who fully anticipated the fulfillment of John’s millennial revelation of the kingdom of the Catholic church, who awaited the resurrection and the final judgement day. This was especially true in light of the prophecies about Rome and the Roman Empire which had been fulfilled almost to the letter. In those days, the visions of Tertulian, Lactantium and many others who predicted the end of the world after the thousand-year kingdom of Christianity were al so quite readily accepted. The very expectation, so widely accepted in the Middle Ages, of the fulfillment of the apocalyptic vision probably influenced Philip II. Because of his important position and his influence, he thought it his duty to spread Catholicism all over the world. Yet the key obstacle in the way of redemption on a global scale was England. Philip gathered a tremendous Armada – ten times bigger and ten times better armed than the English navy. ln August 1587, after almost five years of preparation, the mighty fleet sailed in calm weather towards England. The leaders of the Armada knew from experience that the ocean remained calm and quiet at that time of the year. But when the Spanish Armada sailed within shooting range of the English coast, a storm began to rage out of nowhere – a storm of dimensions that had never been seen before or after that event. Philip’s Armada was totally destroyed. We can only wonder what would have happened to Isaac Newton if Philip II had managed to land on English shores. We can al so only wonder how the Spanish King’s “Ioyalty” to God would have manifested itself. After the catastrophe, Philip felt certain that he had not been humble or faithful enough and that the storm was “God’s warning”. He retreated into total asceticism and prayer. But I don’t think that Philip II or Catholic Church really wanted to understand the true message. In any case, such understanding would have been impossible in that day and age. The Catholic church had to operate in accordance with its goals and duties; it had to spread and uphold the knowledge of God, to expand the gospel, to maintain the integrity of the Church in its fight against heresy. It already had an inkling or perhaps even fully understood the ways of mankind, its inclination toward anarchy that had to be checked and restrained. Bosch depicted that anarchy in one of his paintings though he did not himself experience the glory of the prophet. Indeed, at one point in his life, he was even declared a heretic. King Philip II was not.

Pieter Bruegel, the Elder magnificently represented this period of Spanish conquests and inquisitions, war and plague and the other spiritual and physical horrors of his time in the remarkable painting The Triumph of Death. Bruegel reveals in his paintings the dual aspect of human life. Joy can been seen in the playing children, in the folk customs, the weddings and the harvests and the wonderful landscapes and scenes of humor, in the real human paradise to which each individual can only come by eating through a whole mountain of rice. Nothing is freely given in this life.*

The other side of human fate is symbolized in Bruegel’s famous painting of a blind man leading other blind men. This is al so a metaphor for the modern world, especially for the twentieth century. Bruegel was no longer obsessed with the end of the world and the apocalypse. Although The Triumph of Death is full of symbolism and mysticism, it clearly shows that the eventual end of the world will not be caused by God but by man himself. That death is the ultimate payment for everybody – for the good and the bad, the great and the small, the rich and the poor. It is one and the same for all people whether they have made this world more noble or have sought to destroy it.

Yet the conflation of death and the apocalypse has been shown throughout human history: from the well known battlefield of Krapina where archaeologists dug out over six hundred burnt skeletons with smashed skulls to the mythological Flood to modern-day Srebrenica where, sitting at home in our armchairs and munching on crackers, we watched the slaughter live on television. Violent mass death is scary but only to a certain degree. After three months of killing and the exile of hundreds and thousands of refugees after World War II, Tito declared: “That’s enough; death has no effect any more.” Ivan Grol commented, “This is not a state, it’s a killing field.” Although mass death can function as atrocity, as a threat or a warning to those who still live, the singular death of a loved one is the most tragic thing of all. Love experiences and feels death the most profoundly. Death is personal and it has the strongest affect on people who love. The tragedy of death can only be relieved and made purposeful by faith. Human reason, philosophy and science indirectly help us to see the greatness of Christ’s existence among people, his redemptive sacrifice for mankind, his way, his understanding and his love for man. He showed us the way which sooner or later must become the common way of reason and spirit.

A tendency towards perfection is immanent in human nature. The Church confirms this with the words of Pope John Paul II: Do not fear God but pray with me: Our Father (Matthew 6:9). Do not be afraid to say: My father! Wish for yourselves to be perfect because he is perfect. You, therefore, must be perfect as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Matthew 5:48).

Perfection is only possible in the wholeness of man, in his autonomy, in his own way on which he is directed by spirit and reason. The way represented by sacrifice and love.

But the role of God and his purpose in the creation of man are transparent despite the prediction of the end of the world and time

As a thinker, Spinoza concretely defined the tendency towards perfection in four points:To thoroughly know one’s nature in order to make it more perfect and, at the same time, toknow the nature of all things as much as it is necessary.

Using this as a foundation, to correctly classify differences, agreements and opposites of all things.

To understand what can be born and what cannot be born.

To compare this with the nature and abilities of man.

ln this way we will more easily see the highest perfection which can be attained by man. Perfection can thus be simultaneously complemented and controlled. It is open in all directions.

Perfection is also expressed in Spinoza’s belief that God and nature are the same, or that they are inseparably connected, just as body and soul are inseparably linked in man – uniquely.

Friedrich Nie1zsche in Zarathustra articulated the highest philosophical idea of human perfection.

Before the era of science and reason which arrived with the Renaissance, mankind invested its creativity and other resources principally into spiritual development. Only later would it be invested into science and technology. Now those two goods have overwhelmed the contemporary world. Art – which in my opinion also encompasses perfection – shoulders a huge task: to unity spirit and reason in a poetic message at a level of truth which, I believe, is not yet apparent in science and technology. Many scientific truth s have been discovered and they are becoming more and more universal and continuous. Nevertheless, they all stop before the limits of knowing the material and spiritual Universe.

Dr.Tine Hribar pointed out both the relativity and the transitory nature of the truth s of the mind. In 1981, in a totalitarian space with only one truth, he wrote the famous statement: “The truth about the truth is that there is no truth.” Today, of course, this statement can not be compared with the truth that is being anticipated or proclaimed by thinkers, artists, scientists, and theologians throughout the fields of science and art, love and politics. Derrida would call this “the knot of the four threads of truth”. And here we can see the great significance of Christianity which, as a modern religion, must accept this challenge and create a balance with science and technology for the sake of mankind. The conscience operates on the level of man and not on the level of art or science. Therefore Christianity (represented in Slovenia by the Catholic Church) is directly called upon to find this balance because science and technology, in their enthusiasm, strive to change the world and as a parallel phenomenon to change man, to make his origin null and void, to transform his soul. Throughout history, there have been numerous attempts to change man by force -with floods and sulfur and fire which were supposed to cleanse the world of evil, of the debauchery of hedonists and idolaters, to create conditions for a new generation as we can read in the Old Testament. The saying “Mene, tekel, upharsin” dates from those days. This saying also figured as a slogan for modern totalitarian systems when they wanted to transform man from an “old-fashioned religious being enslaved by liberalism” into a new man fashioned by fascism, socialism, communism, Nazism, new life, science, technology, bio-engineering and so on. Great societies and grand ideologies, various cults and secretive media institutions, operate very successfully by means of brainwashing. In the Renaissance, however, parallel with Christianity, the long hidden Greek image of man arose again. On this basis, the great ethical thinkers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries prophetically constructed the foundation of liberated man. In his famous novel, Brave New World, Aldous Huxley described in a visionary way the scientific ecstasy which of ten accompanies the liberation and creation of “the new man”. But in order to create the new man of science, we will al so have to learn how to clone the soul or the new man will be nothing more than a robot: Robots are made of tougher material, are more successful and durable and, above all, are more reliable than man. Yet the greatness of man, his responsibility for the world, resides in his origin. The Catholic Church recognizes man’s greatness to the highest degree and in turn carries its own burden of responsibility which it cedes back to all people. Not to all people alike but to each depending on how big a part of responsibility each individual, with his own free will, can take upon himself. For a few, this decision is made easier by an inner voice or a vision which is why love and faith are so important in human life. The phenomenon of the god-man, Jesus Christ, is a turning point for human history. It is accepted not by force, not by violence or strength but with love – love for nothing -, kindness – kindness for nothing -, with forgiveness and suffering and the sacrifice that Jesus Christ revealed to man and mankind. Not with some quantum leap and not to some new man. But to the ordinary man, to the man who keeps developing himself and becoming wiser on his own way of the Cross, always striving to defeat evil. This way is a slow and painstaking process full of opposition and misunderstanding, egotism and evil, yet it is inspired by the radiating of something good, something full of love and godliness, something that gives mankind hope and greatness on its way. The old man Simeon said to Christ that he would be “the sign that all others would oppose,” and today John Paul II says: Do not fear the divine mystery. Do not fear his love. Do not fear either man’s weakness or his greatness! Man does not cease to be great even in his weakness. “Do not be afraid to bear witness to every human being from conception to death.”

3. The rational frame of poetics and the divine

Saint Paul wrote, “And if Christ has not risen, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is devoid of truth and is fruitless” (Corinthians 15:14). Nikola Tesla revealed in his notes that he had discovered the majority of his new ideas with his inner eye. They were not, in fact, the products of rational logic or the combination of already existing ideas. The inner voice which revealed to Saint Paul, the Pharisee who hated Christians, the greatness and purpose of Christ’s Resurrection on his way to Damascus – that inner voice has the most important destiny for mankind. It heralded the beginning of the universal Church in which all people became equal before God: “For God shows no partiality.” (Romans 2: 11 ).

Science and technology, with its scientific images and explanations of the universe, has impetuously penetrated the world of philosophy and poetics. Wittgenstein commented, “The only task that remains for philosophy is the analysis of language.” Perhaps because of this very statement, Wittgenstein is, in the opinion of many leading scientists, the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century. Probably such scientists wish to explain the universe just as the philosophers have without being limited or mocked by real philosophers or the poetic dreamers who possess a different, much more penetrating, profound and sensitive vision and are thus able to articulate artistic messages. Descartes made the first step towards the reconciliation of poetics and philosophy with the articulation of his attitude to poetry. But only in the last hundred years – following the revolutions in science, the epoch-making discoveries about the nature of the material universe which caused a cognitive shift towards positivism – has poetics become an important part of the thinkers’ task. The very greatest philosophers have spoken of the poetic dimension of cognition: Martin Heidegger, Friedrich Nietzsche and Emmanuel Levinas, on the one hand, and the enlightened Pope John Paul II, on the other.

ln Slovenia, very few individuals have enriched our mostly positivistic space with this connection, that is to say with a more poetic philosophy. Pirjevec, Urbančič, Komelj, Kermauner, Cankar, Bartol, Ramovš, Zajc, Taufer, Strniša, Smole, Božič, my father and several others are among the few. Of course, I don’t mean to deny the greatness of other Slovenian thinkers and creative individuals from Janko Kos to the beautiful ideas about man and his creativity articulated by A. Trstenjak and other theologians and priests who maintain faith and pure thought.

And, of course, the psychoanalytical attitude towards art is also extremely interesting. One fascinating example of this which should not, however, be generalized, is the thinking of Sigmund Freud about Michelangelo’s Moses: “Works of art have a strong impact on me, especially poems and sculptures, less so paintings. This lack led me to stand before them for a long time, trying to understand them in my way, that is, to understand where their influence comes from. In cases where I can’t do this, for example in music, I am almost incapable of enjoyment. My rational or perhaps my analytical inclination resists being overwhelmed without knowing why and what the reason is behind it.”

The core of poetics lies in its transparency and purity, in its mysterious glow, in the spiritual sphere. It can only be truly experienced in the symmetry of the sensual and the rational, of the subconscious and conscious minds. It can never be totally, rationally clarified or explained. Such eager attempts are sooner or later followed by the inevitable realization that poetics alludes or escapes; it leaves behind naked words and rhymes, notes and brush strokes, a real or perhaps an invented event, a gesture or a look. Empty faith and an absurd amount of words does nothing to explain what is left behind. Indeed if poetics could be rationally explained, then what good would it be?

Where are we going? is the third question of man’s essence – or rather, of his mystery. This is a great challenge for the entire human race.

This question was first asked when God expelled human beings from Paradise. In the First Book of Genesis it is written, “And the Lord God said, Behold, the man has become like one of Us, to know good and evil and blessing and calamity; and now, lest he put forth his hand and take al so from the tree of life and eat, and live forever – Therefore the Lord God sent him forth from the Garden of Eden to till the ground from which he was taken. So drove out the man; and He placed at the east of the Garden of Eden the cherubim and a flaming sword which turned every way, to keep and guard the way to the tree of life.” (Genesis 3: 22-24)

The Lord God knew well why the Garden of Eden and the tree of life had to be guarded. Sooner or later, man would come knocking at that door. The universe – and the human beings who occupy it – live in a fleeting time, a time of transformation and death. There is no time in eternity, at least no time that means anything to us. All things are different in eternity and that is why the Lord God must protect the Garden of Eden.

So then: Where are we going? Are we going back to the stars, to eternity, to Eden itself? Mankind and science are now engaged in a game where everything is at stake – the fate of mankind and the fate of the planet as well. Whether we like it or not, we all participate in this game. Whoever stops playing is no longer here. It is a deadly serious game and it is called the human way. It is the path we create, whether we walk upon it or only stand near it. Whoever we are. For many of us, it is Christ’s way.

Sooner or later science and technology will meet (or perhaps they already have) the fate of Raskoinikov, the criminal. They will discover the conscience, the embodiment of penitence. The Catholic Church itself encountered this truth in its own time (although Dostoevsky himself had not yet been born to articulate it). There is no more space for mercy, for love of nothingness, for human fragility in either science or the art industry. There is no room for powerlessness or for the good hearts of people who have made and are still making happiness in this world. Innocence, trust, faith, goodness, a conscience are considered weakness, the vulnerable spot of the man liberated by science. They are considered a flaw.

Throughout history, great powers have shaped the world and its morality. Today America is supposed to take responsibility for the world, at least for that part of it which is led by science. Will this science ever have an understanding of Raskolnikov’s crime, an understanding of his liberation from his own self-imposed role, that of a superior power in a world which allows the powerful everything? Even crime.

1992, the Vatican asserted that the horrible pollution of the environment is the result of moral crisis and that this crisis is the consequence of an unnatural and immoral vision which, in fact, despises man. In the great performance of science and technology, poets and thinkers are of little importance; they have been marginalized. Yet they can participate in the performance. They can make their poetic tradition “scientific”, transform it into a rationalistic artifact and, if possible, they can “update” it cybernetically, surrendering to the overwhelming “truth” of scientific “development”. Or they can retreat into a sort of psychoanalytical self-disclosure, to a place where Sigmund Freud (or one of his modern adherents) is satisfied to analyze the author’s subconscious traumas, as Freud himself did with Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In embracing the psychoanalytical nature of literature, Freud endorses the view that only psychoanalysis – the reduction of all topics to Oedipal themes – can resolve the mysteries of that tragedy. “And before, what a profusion of different and incompatible attempts to explain, what a variety of opinions about the hero’s character and the poet’s aim. Did Shakespeare really demand that we sympathize with a sick man or was it with a dissatisfied inferior person or an idealist too good for the real world? Thus it is possible to reveal the thought and contents of a work of art. Thus it is possible that such a work needs explanation and only then can we understand why it made such a mighty impression on us. The impression will be no weaker.”

If Freud believed that science and art were indirect or direct responses to the satisfaction of basic human instincts, Carl Jung recognized the beginning of man’s symbolic activity and inclination toward certain basic images inherited by every man and representing the essence of eternal wisdom. With these archetypes, Jung gave us back at least a little faith in the basic human questions: Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? Such questions do not merely refer to biological propagation and survival. Rudolf Arnheim feels a similar disappointment in the doctrine of archetypes when the creative comprehension of Leonardo da Vinci or Henry Moore are reduced to images or symbols of the great-mother Earth or goddess Earth and thus works of art are once again explained by means of Freudian instincts.

I think that here I should mention an important dilemma in the comprehension of global art. As an example, I shall compare Rudolf Arnheim’s essay Picasso’s Guernica: The Genesis of a Painting and Guernica – Essays on Painting, Politics and War by Tomaž Brejc. I first saw the original of this mysterious painting – one of the most important pieces of visual art created in the twentieth century – at an exhibition in Madrid after I had read both essays explaining it. The difference in interpretation revealed in the two essays is so extraordinary that I think it is important to point out at least some of the dilemmas that emerge from that difference in order for the reader to understand my thinking. (A thorough analysis exceeds the frame of this work and for this reason my statements will be more quantitative then qualitative.) Dr.Tomaž Brejc, with an extraordinary deductive approach containing all the logic of an investigator, a prosecutor and a defense attorney, managed to present to the jury (Le. to his readers) al most all the circumstances and, above all, the facts that pertain to the creation of this painting. From the first sentence – so beautiful that I quote it here, “In the middle of the city, on a hill that rises from its center like an acropolis, an oak tree grows.” – to the conclusion of the essay quoting Roland Penrose’s thought, “The power of the painting Guernica will continue to grow,” the author carefully unites all the particles and parts pertaining to the work into a whole picture.

Dr. Tomaž Brejc said almost everything that there is to be said on the topic of Guernica. His work is doubtless a masterpiece. We could call it Tomaž Brejc’s “anatomy lesson of Guernica” but the painting doesn’t come to life in this masterpiece. It remains an object. The world is like Rashomon; the truth can only be seen from another viewpoint. Almost twenty years before (although the reverse chronological order would be more logical), Arnheim had dealt with the painting on a totally different basis of knowing, knowing about ”the vestige of the other” and Guernica’s life as an organism. Arnheim doesn’t start his essay with the fate of the painting or the truth about Guernica. First, he asks himself who is man. Who or what is an individual? How much can we know about him, or more precisely, how much can we know about ourselves? How much do we let others know about us? What role do Freud’s instincts and Jung’s archetypes, inherited from millions of years of human presence on the planet, play here? What do we know about the mechanisms of creation anyway?

Arnheim modestly answers these questions with the hope that he will succeed in revealing that, even when we know the artist’s deepest intentions, we still won’t know the essence of the painting. Because it is not only a message about Picasso; it is al so a message about the condition of the world. The origin of art is the origin of the human race. Therefore, the condition of the world cannot be contained in a single fatal or redemptive deed or event but only in the flow of the conscious and subconscious. For example, in the living Guernica, in its life and liveliness. Arnheim picturesquely depicts the flow of the conscious and subconscious as the same river which flows half of the time in the light of day and half of the time under cover of night.

Personally, I think that Picasso succeeded in painting this daily and nightly flow of the same river. The essence of history. That is why Guernica is not only a painting about death but it is also about love, tragedy and transcendence. Picasso knew all too well that death is very personal and it mostly effects fellow-men, that is those who love the deceased person. The death of a loved one is the most tragic thing there is. Particularly if the death is not natural but is violent. The painting does not speak of mass inflated death. (It does not, for example, depict our reaction to the death of millions of soldiers and civilians killed on the battlefields or murdered in camps or, to cite another example closer to home, to the tens of thousands of our own compatriots maliciously killed in the days after the end of the Second World War). The painting addresses the personal death of each individual, the personal tragedy of each survivor who lost someone they loved. Which is why it al so speaks of love. Picasso is not one of those “philantrophists” who “love” the human race while killing individuals. To the contrary, he sympathizes personally with each individual. The death of a warrior can also be symbolically identified with the death of a nation, the Basque nation. Though for me, this possibility seems strange.

The lantern in the painting illuminates the scene of the crime like “God’s eye”. This means that nothing will be forgotten. An angelic female figure descends from heaven and lights the candle in eternal remembrance of the dead. This is the transcendental element of the painting.

When Kahnweiler, stimulated by the questions of many other people, asked Picasso about the meaning of the horse and the bull in the painting, the painter answered very clearly: “The horse is a horse and the bull is a bull. They are both animals which man can skin.” Whoever has seen the horses and bulls in the caves in Lascaux and Altamira, whoever has the seen the sacred Egyptian Apises and the bulls on the Knosos frescos, knows that what Picasso said in two sentences is a message that has of ten failed to be contained in a whole book. Namely, he conveys the truth of the European tradition and of its violent interruption. The interruption is in the loss of poetics. But Picasso does not say who the culprit is.

Everything in the painting accords with tradition and yet there is nothing obviously traditional about it. Tomaž Brejc wrote, “Only now, faced with the changes in the contemporary art world, have we become aware of the fact that Picasso was deeply anchored in the nineteenth century tradition.”

Personally, I know of at least two nineteenth century traditions which have strongly influenced the art of the twentieth. Marx saw the deliverance and liberation of man as a total break from a past that burdened him with religious, philosophical, behavioral and other traumas. Marx believed that it would be best for this new man to forget even his own maternal tongue, his commitment to and dependence on family and nation, his tradition. Marx believed that the new man should start anew on solid ground, on the planet Earth where the sky means weather and everything above is either white-hot or dead matter. The great master, Rihard Jakopič, wrote: “Everything born out of materialism is hollow and deceitful; it will only last until tomorrow.”

The materialist tradition of the nineteenth century gave birth to the revolutionary art of the twentieth century known as the avant-garde. This includes everything from the European futurists to the post-war American art scene – financed by some two billion dollars – which transformed the endeavors of European artists from the beginning of the century into post-war explosion and inflation of the “avant-garde” and which was accepted even by the Yugoslav Communist Party along with abstract art, Coca-Cola and the entertainment industry.