III. FACE OF THE SOUL – The blossoming people

Human memory is an incomprehensible thing: for example, I can stili vividly remember even today how, as a child, I observed two small blueberry bushes, how the tiny leaves of each had a different shape and color. One was almost completely white and the other dark violet. Only the blueberries were the same color and all were equally delicious. Yet I can’t remember the faces of children with whom I wandered through the woods in those days. And I can’t remember the faces of the schoolmates and schoolteachers I knew in those years. I do, however, retain in my mind a vibrant picture of the face of a poet whom I saw only once in the dim light of my bedroom. The beautiful blue eyes of the little girl I met at the square remain vivid in my memory and I al so remember much later a blue-green butterfly of the same color glowing in the twilight of a ballroom. I w.as overwhelmed then just as I had been overwhelmed when I observed from behind a bush the milling crowd in the church square. Only the second time I was sitting at the edge of the dance floor, bored to tears, waiting for my old er brother to stop dancing so we could go home. Fortunately, the dance soon ended and I didn’t even notice the man dancing with the wonderful bluegreen creature in the silky blue dress scattered with green patches like a beautiful peacock butterfly. Without hesitating, I approached Anka – that was the name of the butterfly – and introduced myself. And it was forever. I knew that the moment I plunged into her heavenly blue eyes.

I don’t remember any of the acquaintances with whom my brother and I kept company at that time. They have disappeared into the opaque depths of memory or perhaps they don’t even exist there any more. I do remember that I only accepted people who I thought had pure hearts and spirits. These were qualities I sensed in people as I would a buck or a doe hiding in a dell where nothing else could be seen or recognized. I simply knew they were there. If I stayed in the forest long enough the animals, even the foxes, also came to accept me. They no longer feared me. I had somehow became one with the forest. I knew that a hunter was coming when the animals grew cautious and then suddenly disappeared.

ln a similar way, I came to know Anka and all the friends who have blessed my life. We simply found each other, felt each other regardless of what or who somebody was, where he or she came from. This is the way I got to know all of my friends. I call them the blossoming people. They were like great brown or delicate blue peacock-butterflies, frolicking about, flying free above the flowers and the grass, heeding neither birds nor lizards nor the little hands that long ed to seize their flying freedom. I remember well the day the poet was killed. I saw my mother crying and thenI, when I heard of his death, rushed out of the kitchen to the street. I ran and ran as if by running I could tear the pain out of me. I wandered the streets and finally when the burning in my chest seemed absolutely unbearable, it was replaced by the need to pee. I slipped into a dark entranceway and began to pee when a roar seemed to come right out of the wall: “They piss on my head! The swine! I’ll kill them!” My heart fell into my boots and I fled along the dark passageway, panicking, getting lost in the unknown corridors of a cellar. At last I found myself in a totally dark and hidden place and felt a door in the wall. I pushed the creaky door opened and stepped into a room that exuded the stuffy odor of old rags and rotten wood. I sat down on the rags and quietly sobbed.

“What mischief have you got yourself into?” said a low voice beside me. I shrank from the voice but soon my fear dissipated because I could teli it was the voice of a boy. “My name is Franci,” the little voice said, “and when I do something mischievous, my mother drags me down here and ties me to this broken divan with astring. If luntie the string, woe is me! And who are you?” That’s how Franci and I met and after that I visited him frequently. Soon I could find my way along those dark corridors as if they were brightly lit. I came to recognize all the big and small curves, the openings, the traps under the stairs which were each a different size. Inever had any trouble finding Franci’s room and his divan. “If you are in the dark for a long time, you start to recognize specific objects and the little animals who live in the darkness sooner or later get used to you.” He said this when a big fat rat smeli ed me and then crawled away when it realized that I wasn’t food, at least not yet. Gradually, I managed to make him teli me why it was that his mother always caught him whenever he made mischief. He told me that his father had abandoned his mother when he was very small; he had left for good. Then he showed me a photo of his father and his situation instantly became clear to me. Franci’s resemblance to his father was so uncanny that he must have served as a constant reminder to his mother. So he resigned himself, suffering from the traps and cruelty with which his mother caught and punished him. He couldn’t see any solution to his problem. God forbade him from untying the string. He had tried it once and was stili horrified by the consequence. He became utterly terrified when one day I arrived with a needle and skillfully began to untangle the knots. I was quite skilled at this task because I had always unraveled my fishing line which got tangled in the most malicious and insoluble knots. In those days, you couldn’t just get another fishing line so I worked with the utmost determination. Franci and I spent a lot of time keeping each other company.

Franci rarely went out to the street. He often broke into lofts and cellars but he never took anything. Many years later he confided to me that before we met, pigeons and rats had been his only friends. He knew who lived in almost all of the old town houses. Franci was the one who introduced me to Miro, the shoemaker. One day while walking down the street talking about pigeons he disappeared in mid-sentence. I caught sight for an instant of the back of a woman vanishing behind a house. The street was empty, all the doors were closed, the shutters of little shops had dropped to the floor. Nobody anywhere. Astonished, I looked around me when all of a sudden Franci literally unglued himself from a wall, fell into step with me and continued the conversation as if nothing at all had happened.

When I returned home later that afternoon, a tiny woman of incredible severity and strength intercepted me. Her smile was forced and she didn’t try to soften it. She said she would like to treat me to an ice cream. I firmly refused not that I had anything against the invitation but because I had once got so sick after eating ice-cream that the secretion that had flowed from my body was like bird’s excrement, liquid splashes pouring out of me over which I had no control.

The severe lady didn’t realize this or she might have treated Franci to an ice cream once in a while. The woman, of course, was his mother. She wasn’t sure if I knew anything about her or about Franci’s staying down in the cellar. So very cautiously, she asked me what Franci and I had been talking about that morning. I made such a good imitation of surprise that she seemed sincerely disappointed. Then I told her that Franci’s father, a well-known pub-owner had promised to let his son accompany me to Barje and that that was what we had been talking about. Of course, the pub-owners son was another boy, not Franci. “But you were in the street with Franci when I saw you in the morning,” she tried again and then slyly added, “Anyhow, I heard the pub-owner is in prison.” “I know what you’re saying: you’re saying that his pub is a prison. And I say to you that Franci lives in a prison, too.” The woman was horrified. She begged me not to say a word about any of this to any other living soul because it was all a big misunderstanding. I promised I wouldn’t talk to anybody about it. Then she left, looking like a heron who had swallowed a plaster fish. This description was not coined by me but by Franci who was sometimes successful in convincing his mother of his innocence when he had gotten into mischief by spinning such incredible yarns that his mother believed them precisely because they were totally unbelievable. I mention this because there was no pub-owner or pub-owners son, Franci, and also because one couldn’t go to the marshes anyhow because the Citywas surrounded by barbed wire. The severe lady, of course, didn’t believe a thing I said. She did know, however, that I did not simply make up the story. After that meeting with the severe woman, Inever found Franci in the cellar again. He became invisible. Inever met him again or saw him in the streets or city squares even when they were entirely empty or brightly lit by the sun. And then every once in a while, he would unglue himself from somewhere like a living shadow and appear right before my eyes. He always smiled kindly. We exchanged some friendly words and then he disappeared again. That was Franci and that was the way he remained forever. He was al so invisible in the pub: he drank a glass of wine and then vanished. When he paid for a drink, the waiter wondered where the money on the bar came from because he had seen no one sitting there. Franci had introduced me to the people who dwelled in the secret mysterious places in the old houses. I was most impressed by Miro. There was something dignified about him and his personage. He was a big sharp man with a huge nose and ears that jutted out from his head. He lived behind the opening in the doorway where I had peed not having the slightest notion that anyone could possibly live there. When we got to know each other, Miro always thought I was hiding something from him. With cunning questions and countless traps, he tried to draw this secret out of me. But he never succeeded.

Miro was a shoemaker. His workshop was located under the monastery church. It was small a few meters long and a good meter wide – but had a ceiling that was almost six meters high and ended in an arch. His workshop had a double door, the outer door being made of iron and equipped with a big bolt and a huge lock. There was a big black boot hanging above it that could be seen from far and wide.

The secret police often broke into Miro’s workshop and left it a mess. They pulled up the floor boards and scattered the neatly stacked pieces of leather. Once they even scraped the plaster from the walls in search of hiding places.

Miro didn’t work on Saturdays and Sundays. He took the boot down, polished it and smeared it all over with black shoe polish to protect it in bad weather.

One Saturday, urgently needing a piece of advice, I paid him avisit. When I knocked on the door, it burst opened and Miro rushed past me after a man who owed him a great deal of money. I peered into the workshop. When Miro had rushed out, the big boot fell over. In the fall, a hidden mechanism had been triggered and unusual objects poured from the boot: astrange black cap, a candie stick with seven holders, a yellow star made of linen, a silky white shawl with wide black stripes and a whole bunch of other knick-knacks. I quickly entered the workshop, put everything back into the boot and reset the mechanism. I ran home and told my father about what had happened. He looked worried and told me in no uncertain terms not to talk about it to anyone, not even to Miro. Otherwise we would all be in trouble. My father and I kept the secret.

Miro knew exactly what was going on in our part of the City. When I had told my father about the dead girl, he had been extremely cautious and reserved. Miro seemed worried too. When I told him that my father was also a bit scared and that he thought her death was somehow connected with the end of the war and that many matiers would soon be setiled in this way, Miro said, “Although I have never had the honor to meet your father personally, I respect him very much. For me, it’s enough to know his venerable son who respects and believes me. I know very well that you told your father about the contents of the boot and that you quickly crammed everything back into it. I would never have done such a thing. The war is practically over yet for some years we won’t even notice that it has ended. People will continue to disappear just as they disappeared during the war. The same waitress will continue telephoning the same police station. Our leaders will stili be beyond reach just as the occupying forces were. It may even be more difficult because if they put you on the spot now, you’lI be marked forever. Down there by the water you will be persecuted by the same policemen, only they’1I be called the militia now. We should expect cruel times and that gi~l’s death is oniyasmalI part of what’s coming. I only know that the victors are at least as cruel as the occupiers were. They are without mercy or sympathy. They learned nothing good from the defeated. Victory is not a tender mother but a wild and prankish stepmother. Capable of the worst deeds. You can believe me. I have lived through this war in the greatest fear and I am even more afraid now.”

I cannot tell you what happened to that girl so I shall teli you something that happened to me. Soo ner or later you will find the answer to every question that has been nagging at you – including the question of the girl’s death. But you will have to form your own opinion and keep it strictly to yourself. A nation – and this is ancient wisdom wrapped in the remote mystery of origin – consists of many people: good and bad, good and evil, friends and enemies, deceased, living, disappeared. It consists of everything people have known in the past, what they know now and much much more.

Once when I was up in the north, I was shown alitile animal, no bigger than amouse, and told a story about it. For years these litile animals live their invisible lives and then one day they all crawl out of their subterranean hiding places. They gather in a huge mass and race away, all in the same direction. They don’t see any obstacles, they don’t care about enemies, they cross ravines and rivers. Only the vast sea can stop them and most of them simply drown in it. But I was not particularly interested in the self-destructive march of these little animals who at least, unlike man when he embarks on campaigns and revolutions, don’t carry within them the passion of destruction and evi!. I was more curious about the ones that stayed home in their shelters and preserved the ways of their tribe. The storytellers looked at me as if I were a fool who had understood nothing at all. With great excitement, they continued their story of the little animals that massed in countless troops, who wouldn’t be stopped by any obstruction during their long magnificent march. It is similar in a nation. You never hear about those who preserve the real notion of home.

Miro disappeared soon after the end of the war. Many years later I heard from an acquaintance, ajournalist who had been in the Near East, that Miro had heroically fallen in action when defending one of his cities. Only then I understood why Miro recalled the lemmings – for that was the name of the little animals – with such fatalism.

My father gave us similar advice: to keep every thought, even the most innocent ones, to ourselves. Of course, he gave us this advice indirectly but he al so sadly added that now all human weaknesses – gossip, envy and other similar things – would become fatal traits. The authorities ruthlessly cleared the City and the Country, preparing the stage for the performance of their most deadly serious play.

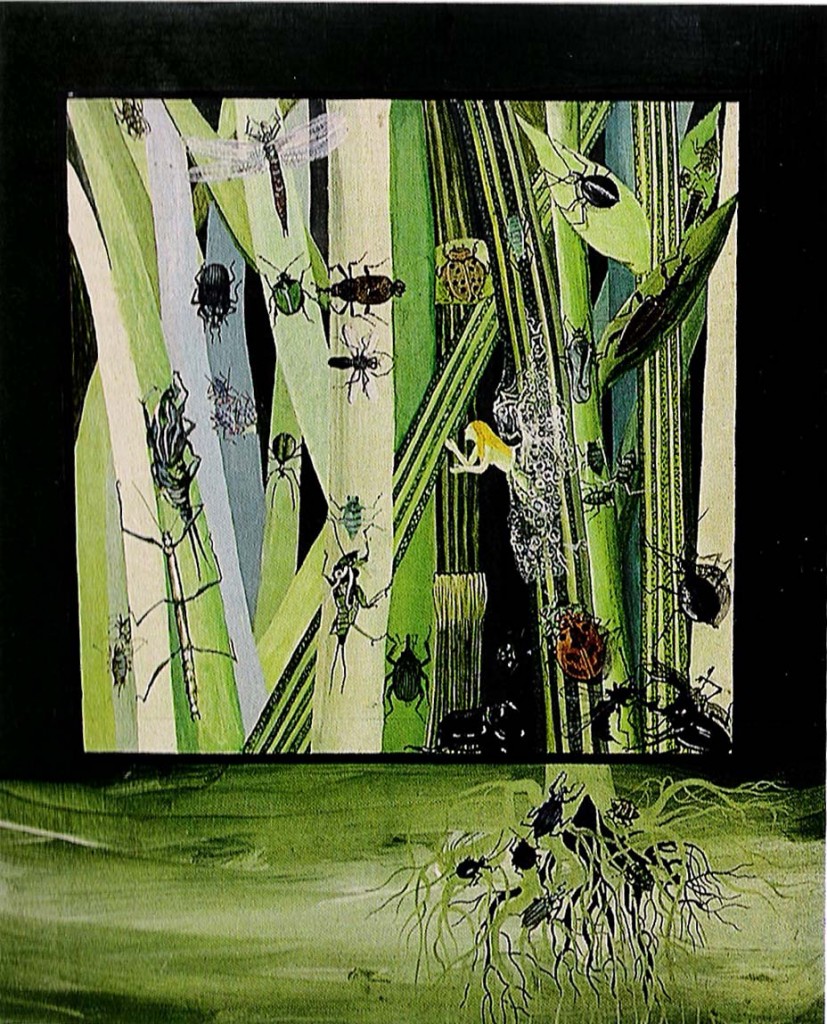

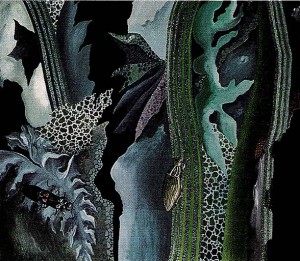

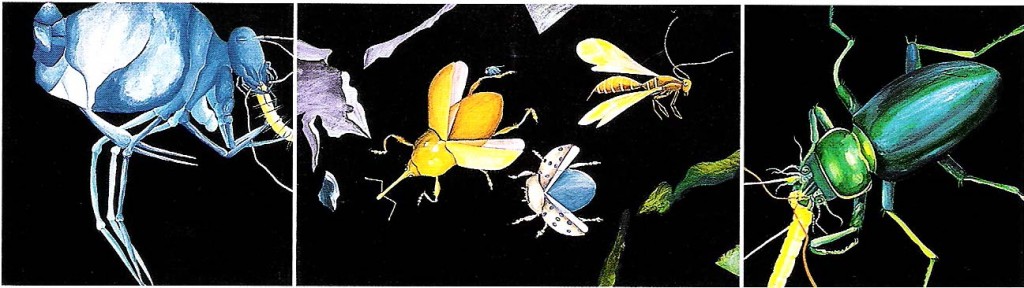

Maksim Sedej yr.: Nothing new about the nature, triptych

Oil on canvas, 135×135 + 135×200 + 135×135 cm, 1967

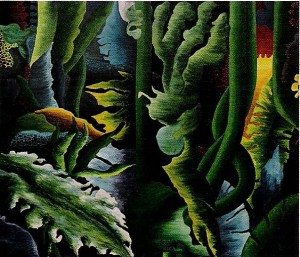

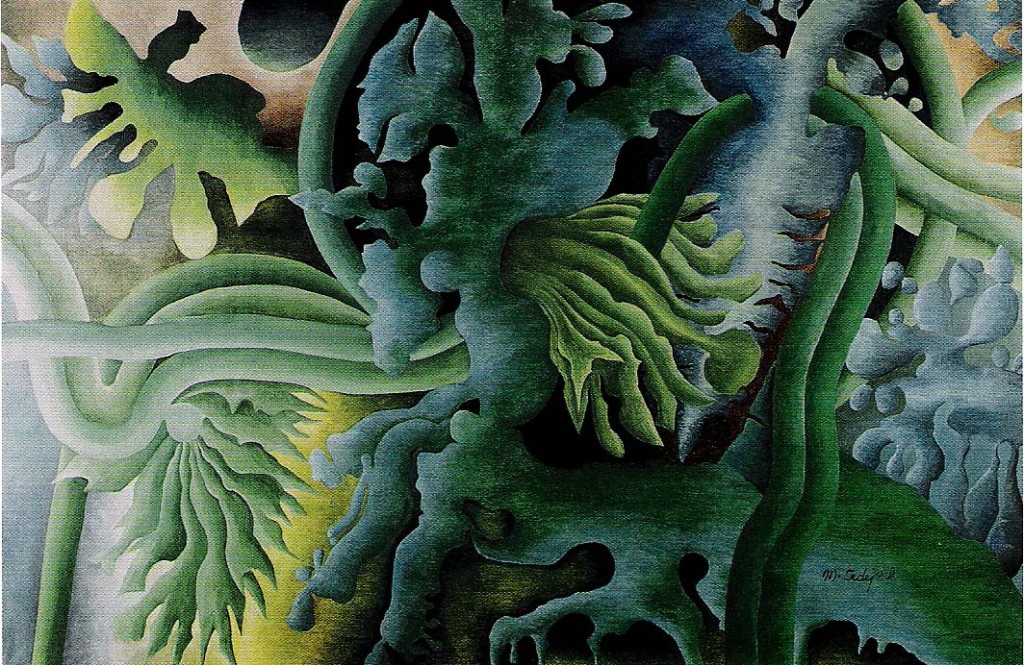

Maksim Sedej yr.: Nothing new about the nature, composition

Oil and tempera on woodpanel, 25×100 cm, 1967

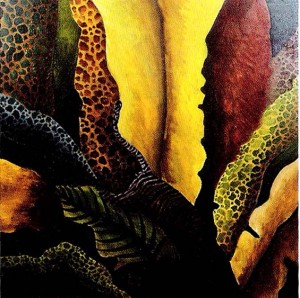

Those were the times when I had my deepest experiences of Nature. Of it’s very essence. Sometimes I melted into Nature and felt a sense of Oneness. At those times, I felt the primeval, ancient, mystical traits of the mankind.

At night the forest becomes animated with mystery; a feeling of primal existence returns to it.

Night is the part of the daily cycle when living creatures recover from the nightmares of the day most of which are created by man. Thus not only the dark, but the daylight as well, becomes a nightmare for living creatures. That is how I saw the City at the time. It was all remote lights and a dull throbbing that sounded like the quiet buzzing of a huge distance engine. It wasn’t even a good place for people, covered as it was with a huge blanket of violet smog that was produced by the City itself and that couldn’t be blown away even by winter storms and spring winds, couldn’t be washed away by buckets of rain.

The City was a foreign body that had landed on Barje like a huge space shuttie; it gave a certain meaning to “all that existed”. From this dualism – between all that I knew about the City and about the whole of Nature – I constructed and created attitudes and relationships that ultimately became the criteria according to which lexplored Creation.

The villages at the edges of the Barje marshland adhered to the outskirts of the forests like tentacles and functioned like a bond between the City, the Country and the forests.

It is possible, but only with difficulty, for those who are extremely strong and vital to survive in the forest. But the destiny of people who sought their freedom in the wilderness of the forest or for that matter in the suburbia of urban civilization was extremely poor. Of course, the notion of Wilderness within civilization is only an iIIusion; every tree, every animal, every blade of grass, every chute for removing wood has its owner. Because of this, I often felt like a thief in the forest, a thief who had to move surreptitiously so as not to be caught by the owner of the land. Anka and I spent many of our youthful years studying the fruits of the forests and the rivers. Anka applied for a grant from the Faculty of Medicine and was rather arrogantly rejected. And nobody was buying any of my paintings. In retrospect though, I’m grateful that they didn’t.

I gradually formed a clear picture of the relationship between the City and Nature. I think that the key problem in this endeavor was to find the right distance from which to observe them. The forest itself was a sort of observatory. During the day, I saw evil and love no matter how mysterious they were. I didn’t see them with my own eyes, in the open or by secretly spying. I felt them in the peaceful silence of the woods. There I was able to feel and understand events, words, love, anguish and fear. Evil, as well. I recognized these things in people without having any clear paIpable reason for doing so. I felt them in the City.

And from my room or leaning out the window or looking at a book, I observed distant nature. I sensed it through the haze and the smog which hindered visibility, prevented clear vision. From books, I gained a knowledge about nature that iIIuminated even the darkest nights. Yet because the facts about the stars and the universe, about life and being, were so of ten presented in an accurate and prosaic, indeed in an almost cruelly realistic method, I realized that I would not be able to learn faith and admiration for Creation only from books. I realized that this special kind of grace was passed down from one’s ancestors and that this faith, which I could al so name the call of Nature, is the foundation of all. This faith is the purpose. At least it is for man.

Only with faith in God is love for one’s fellow man possible. And vice versa: only with love for one’s fellow man is faith in God possible. Therefore it is not possible to make a one-sided deal with God, a deal that is not based on love. Faith without love and forgiveness is an empty faith and it can only provide comfort in the cruel everyday reality of survival.

Quite soon, I felt this cruel reality of survival at home. The atrocities that were going on during and after the war changed people profoundly. They usually gave up and simply became part of the System, accepted it with all its cruelty and its false promises of a brave new world. They became new people.

My father’s circle of acquaintances and friends grew smaller and smaller with each political tri al , with each disappearance of one his friends, until it was finally reduced to a few individuals who existed only at the margins of the society, between the light and the darkness. Only a few individuals who felt free enough to choose their friends and acquaintances in accordance with their own feelings.

My father was never a mystic. He believed deeply in art and love but his benevolent social belief – which he had openly expressed before the warwhen he sympathized with Miroslav Krleža, when he had befriended other people who shared his views, views which he had depicted in prints of social themes – experienced a total and dreadful collapse under the System. He buried politics like a thread of truth deep within his mind. The family, which for him was the basic celi of civilization, acquired different dimensions. The System existed above everything, above the family as well. In order to maintain his family, he preferred to illustrate fairy tales than to submit to the System, than to paint its glory.

More or less the same pattern was repeated all over the socialist world: it was not enough to blindly belong to the System, the family had to be crushed as well. It was only possible to survive if both parents were employed. Every individual had to support himself. The wonderful pictures of the family and its members that father had created with such love lost all meaning in the impersonal world of the System. Even today when the System has been subdued, my father’s paintings of the family continue to represent images of another and different civilization. During the years of occupation, it was possible to survive even without a job but after the war such an existence was no longer possible. The values which had gave meaning to European culture and civilization were substituted by the very different values of the System, some of them diametrically opposed to the previous ones. And so those idyllic portraits of the family and its members that my father had painted were transformed under his brush into a nightmare of alienation – into decay. He iIIustrated his own role in that world with two self-portraits: in one he depicted himself as a corpse in a coffin and in the second at a funeral where authoritarian monsters play Memento mori beside his body. *

There wasn’t much choice: either you became a loyal member of the System – albeit with fingers crossed in your pocket – or you isolated yourself in your own private world to the extent that that was possible within the System. And there was also a third option: to remain a true believer and thus a third-class citizen, to land at the edge of the System and engage in a Don Quixote-style fight for justice and truth. But for what truth?

These self-styled Don Quixotes, with their work and their very existence, brought light into the darkness of the System. These were the blossoming people who searched in the depths of their minds for poetry, faith and love, who discovered the many paths to the truth. They didn’t pursue the grandiose and infallible singularity of the System’s truth. Instead they discovered and followed the truth that revealed the whole of Creation, the whole of people with all their differences, their mysteries, their inspirations. They were the only really proud people in the System. As for the others, the dictators substituted pride – which in any case they didn’t possess – with self-conceit. I must admit that Anka and I took the third path – albeit almost subconsciously. We never spoke of it; it was as natural as our love for each other. Anka and my father were the first and the most wonderful of the blossoming people.

As I came to know other blossoming people who brought otherness into the System, its dark opacity gradually became more transparent. It was possible to see the most dreadful things that lurked like dreadful beasts in the hidden depths of the System. The most impenetrable darkness containing a watching beast is stili, unfortunately, the System’s essence. Up until today, no word of repentance or human grace or mercy has yet been uttered to excuse the horrors which were committed in its name.

This beast has always represented human evi I in the System. It tirelessly maintained and consolidated its authority with the accuracy of a computer. It controlled culture, material goods, mass media, morais; finally it sought to control the meaning of the brave new world itself. At first, the beast satiated itself with blood and the primeval human fear for sheer existence. Then it cut down the growth and expansion of otherness by means of small and large trials and various interventions into daily existence. Sometimes a mass media agitation was enough for frightened Slovenians to voluntarily request legal actions against the representatives of otherness. The pervasive feeling of the presence of evil was probably the worst element.

And let it be said that this evil didn’t only spring from the System itself but also from the opaque depths of the victims who had been physically or spiritually hurt and even destroyed by the System. The belief that ideology didn’t matter at all was the most tragic. What ultimately mattered was the unlimited authority that held out to individuals all the benefits of a material, secular life. At certain times in those years when I was seeking the political dimension of truth, I had to enter through my own painting the life of the mystics, of faith and love, the logic and reasoning of an observer who was not indifferent to the System’s performance. I had to cultivate such an attitude to the System so that it wouldn’t suck me up, so that I wouldn’t be occupied by its temporallimits.

My blossoming people served as an inspiration and gave me hope that everything is not in vain. They allowed me to set the distance, to take a global view of the System and to paint it. *

At that time, Anka was reading Plato’s Symposium and we got the idea of holding agathering in our home. Sometimes a group of us would have a picnic at ariver. Almost all of us began to meet in this way so that we didn’t philosophize on our own like hermits.

During those years, the world was seething with all sorts of demonstrations, protests and revolutions carried out by youth – sometimes carefully organized, sometimes spontaneous – to change the world of their fathers, to take their share of responsibility in the new world. In China the cultural revolution, supported and backed up by the top communist leadership, destroyed all bonds with the past and the dimensions of this upheaval only grew more and more dreadful.

The System was based on power. The greatest and deepest presence of that power resided in an ideologically-organized army that, following the civil war, committed itself to communism and performed horrific massacres and deportations of all other nationalities from the state. They did precisely what the Fascists and Nazis had failed to do owing to their slowness and lack of will.*

The System built arepressive machinery which by the sixties already functioned automatically. Everybody knew what they were expected to do and how they were supposed to do it. This meant not only self-censorship but the presence of a phenomenon common to all totalitarian communities: homo duplex, the double man. In private life, they were nice normal people; they were the funny, friendly, moody, merry or sad, pleasant or not so pleasant cohabitants of the System with whom you could easily chat and mix. But it became immediately evident that they behaved in a totally different way within the machinery of the System. They committed themselves to the System because they feared for their own existence; their private life was nothing more than a fiction and a withdrawal from life. Today we might call it “a withdrawal into virtual reality”.

And together they created a new, different kind of middle class based on the eternal ideology of the System in which the values of a genuine middle class were something passe, old-fashioned, contrarevolutionary. This new middle class created after the war had, and will continue to have for some time in the future, supremacy over politics, culture, economy, morals and other attributes of the true middle class and of the nation. In the sphere of art, the monopoly of the Central Committee became deeply anchored in the mentality and thinking of a large segment of Slovenian artists. This had catastrophic consequences on the thinking of Slovenian art critics and theoreticians. Yet regardless of that fact, they now have apparently assimilated themselves into a sort of democratically-directed middle class.

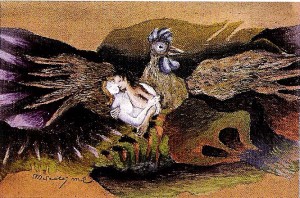

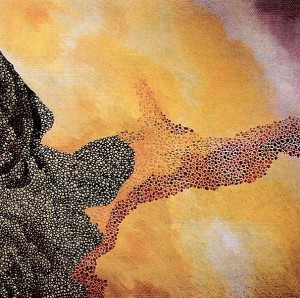

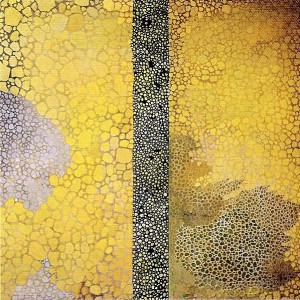

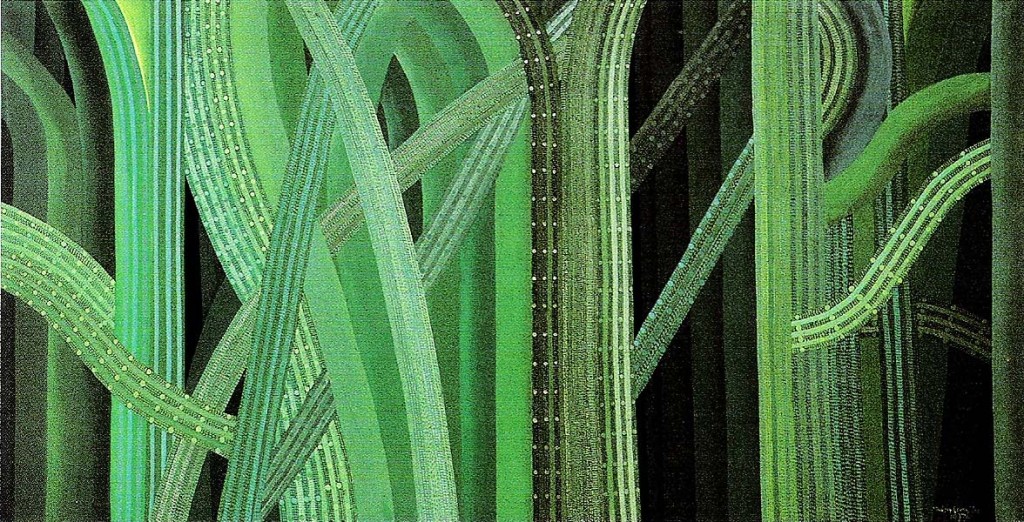

Maksim Sedej yr.: Nothing new about the nature, View in Fountain Green

Oil on canvas, 135×270 cm, 1977

Life at the margins of society did not always go unnoticed. I had my first contact with the political police at home when the magazine Perspektive was banned. Two decently dressed and extremely polite gentlemen searched our pantry, our studio and 10ft and then left without saying a word. Dušan Jovanović and I were the last to be in charge at Oder 57. When we were called in by the police, they greeted us in an almost patronizing way ~md explained to us where the remaining documents and archives of Oder 57 were.

At the time of the painting and exhibition of the Generals cycle, I experienced some measures which were sophisticated for that time but fortunately ended favorably for me. First, the Party Secretary at the party meeting of the daily newspaper, Delo, demanded that a friend of mine, a writer and journalist, end our friendship immediately. My friend indignantly refused, saying that nobody could teli him who his friends were. In those days, the System already functioned routineIy; even marriages and divorces were carefully planned. Naturally the journalistic career of my friend ended at on ce and he landed at a less prestigious editorial office. Soon after that, a rumor circulated that he was working for UDBA – the Yugoslav secret police. This was the most reliable method of destroying groups, friendships and even marriages.

I experienced the second act of this campaign at the Slovenian Artists Association. The president, a member of the Central Committee, demanded my expulsion from the Association. AIthough the president was against my presence at the meeting, I attended as the Secretary of the Association and, because of my presence, the motion was lost by a single vote. But the president had his reward anyway; he became a member of a prestigious group that presented the iIIusion of artistic freedom in the totalitarian state and thus he soon obtained party privileges as well as those of the Central Committee. Not long after this incident, I was invited to the Office of the Secretary of the Prime Minister, Stane Kavčič, to paya courtesy GalI. On that occasion the Secretary of Information, Comrade Severin Šali, explained to me that the people from UDBA “had put their heads together” regarding my Generals cycle and that, for any decisive action to take place, it was in fact a good thing that I had not been expelled from the Association. The Army as the basis of repression was gradually being augmented by the political police force and by the administration of justice , the state bureaucratic apparatus affecting all segments of society. At the top of it all squatted the political bureau of the party like a great big spider. The only artistic approach which seemed appropriate to me was a representation of the grotesque truth about the System and the Army with which the System covered its back and secured its foundations. The evi I that was concentrated in the Army was revealed in its most horrible light during the recent disintegration of the Yugoslav state, in the so-called ethnic cleaning of the former republics and provinces.

It because of the grotesque paintings I was in the process of creating, my awareness unexpectedlyexpanded. I came to realize that criticism of “all that exists” is non-productive in such a System. My cycles of paintings that depicted generais, revolution, the blossoming people wound up with little toy keys, all served to convince me that despite my distance to it, despite my opposition from it, I had also become a functioning part of the System.*

At that time, Ibegan work on two new two cycles of paintings: Here Was aTiger and Nothing New about Nature. I tried in these works to create asimilar distance as the one I had experienced when observing nature from the window of the house we lived in or when watching the City from the woods. From adistance, I was able to see things much more clearly than I did when I melted into them or evaporated above them. But since I also couldn’t be indifferent towards the System, I continued my work entitled The Anticipation of National Pacification.*

The margins of society where we found ourselves – or rather to which we had been pushed provided us with avantage point, if we wanted it, from which we could feel and comprehend. The first step was to stop hating the System, to free oneself of all prejudices and to understand the Universal grace in which we found ourselves. A Universal grace from which we could see both darkness and light and all of the nuances in between. The diffuse light behind which we could make out and antidpate the light to co me as well as the transparent darkness of the System itself enabled us to gradually understand Creation and our personal role in it. The most important thing was to learn to distinguish the darkness which penetrated the diffuse light and the light which penetrated and shone in the darkness. In Slovenia, there existed an additional edge or border between the two systems that controlled our Planet. The West and the East, divided by a firm ideological barrier, met on this border. Yet this barrier failed to distinguish between good and evi!.

Communist systems followed the example of feudal or pyramid structures and created, by means of the revolution, a technological variation on such systems. They replaced God with the distant goal of a classless and just future. The despot and his elite inevitably stood at the top of the system. Untouchable and almost astral, the despot allowed himself everything while reaching for the ultimate goal – his vision of the state and the world. The bottom of the pyramid, its foundation as it were, consisted of the masses of the “nation” which – with its labor, malleability, obedience and blind submission to revolutionary goals (sometimes with real admiration and ravishment) – followed the elitist vision. Between the elite and masses ran countless threads – sometimes fear for mere survival, sometimes revolutionary euphoria – which firmly bound the crowds below to the System above.

The System see med eternal from such a perspective. Despite the rational and radical nature of communism, the masses were possessed bya kind of mysticism which now, for instance, is resurfacing in China to an unimaginable degree. This element was never clearly articulated or defined which is, with out a doubt, precisely why it added another aspect to the System. And on the other si de of the wall, beyond the border, the so-called free world emanated yet another extraordinary vision.

Technology, the entertainment industry and – last but not least – money with its instantaneous splendor overwhelming the remaining efforts of sincere seekers of truth, of the youth who had wanted to build a different world. The free world is al so built according to a sort of hierarchy. It has been disguised in a sophisticated manner but is nevertheless similarly divided into the elite who lead and the masses who implement the technological revolution. But mysticism never made an appearance in the free world which is ruled by pragmatism, relativism, liberalism etc. Almost the entire planet has been submerged in the output of an entertainment industry which creates, with its heroes, a new goal and purpose for the majority of poor and humiliated people. And in this same world, remote dreams of eternity and of eternallife have become, thanks to technological progress, a more and more realizable vision.

But until this dream comes true, the world resembles a sort of waiting room where people live their lives as comfortably as possible, preferably without any responsibility to the planet on which they live. The real border between the light of the lightness and the dark of the darkness revealed to us the enormity of the planets and the infinity of the universe. All too soon we became aware of that fact that we were living in a world where we looked from a darkened room into the lightness. My father once painted a bird cage with an open door. The bird was flying from the cage, out through an open window and into the light.

Of course, one element of the System couldn’t help but penetrate the soul of the observer and the creator of light. This was the emptiness of the System. You see, the System produced only one thing: emptiness in the soul. This is something very different from the emptiness which occurs in the artist after he has finished a cycle of paintings or poems, after he has given birth to a dramatic play or a symphony, after he has exhausted his creative energy, has poured it into his work. Those two kinds of emptiness when combined can cause a bad nightmare, a deep depression, about of heavy drinking to the point of stupefaction. If it wasn’t too cold, I used to go camping at such times. This emptiness, this condition after a creative work of art has been completed, was beautifully and sincerely described by Taras Kermauner in his book The Path Across the Water. For us, freed om didn’t exist in the world outside of ourselves, but in a free world that existed only within ourselves. Freedom meant taking total responsibility for our deeds and that is why none of us really wanted to fly out of our darkened room. We were born in that room. It was our home and our responsibility. For us, the bird cage meant home and we didn’t want to leave it. We couldn’t leave it. So we merely flew through the open door from time to time, into the light and then back again.

When I became aware of our condition, it became even more important for me to expand my idea of national pacification. It was like lighting a candie in the darkened room. Uke in the painting Guernica. Slovenia was a part of the global socialist bloc and, as such, had a specific role to play. Becoming a part of such a huge and powerful movement blurred the vision of all those who entered the System. The area where the light and the darkness met became invisible for them; there was only the border, the wall between the two systems. Although certainly many must have dreamed of the other world, of that brave new world of freedom.

All comparisons came from the other side of the wall. Ideas as well. People simply didn’t believe that the distance from Ljubljana to Andromeda was the same as the distance from New York to Andromeda, particularly if the Earth was actually spinning. Vladimir Bartol always kept in mind this picturesque metaphor – especially when he talked about the origins of art and the artistic vision which each creator must invent for himself.

Ileft my home when I was very young and Imoved with Anka into a new home, a solid one, totally different from the fragile house in which only my little sister, Nevenka, continued shining like a tiny sun. With Anka, I came to know an entirely different world. And though, like most middle class families, it was affected by war and by the difficulty of the postwar years, it remained a world of steadiness, of faith and of hope. Anka’s mother and father and grandmother propped up the family with mutual trust and support and their home provided Anka and me with the strength to keep to the path we had chosen. Anka’s sister, Marinka, brought Ivan Urbančič into my new home and they and their family completed the domestic circle. The large garden behind the house – full of flowers, of vegetables and fruit trees – was the tiny piece of the world where we, the blossoming people, met each other and lived our lives. The blossoming people do, like others, die but they remain forever in our hearts. And then, of course, the margin of society existed as it always has at the edge – which is to say – at the bottom of society. These were the people who found themselves at the very edge of existence and essence and they lived their lives in the Slovenia of that time as they do all over the world. There was no ideology, no faith, no laws of secular society, no morals or other refuse of civilization. Their’s was a genuine Oarwinian world of survival where primeval instincts were always fluid and flowing. But you could find magnificent people in this world. Franci was certainly one of them. He never earned anything nor did his mother give him anything. Yet he didn’t beg or borrow – he always had an ample supply of corn and groats for the pigeons and bacon and cheese to feed the city rats. There were people who insisted that Franci was stealing but nobody could prove anything against him. The rats never accepted me as one of their own. I soon found that out during my visits to Franci. The rats rubbed against him, climbed over his arms or knees. Watching him with admiration, they incessantly sniffed him and nibbled at him. But they paid absolutely no attention to me and I had to take special care not to step on one of them. They considered me nothing.

When I mentioned this to Franci, he told me how it happened. He told me that it took a long time before he became invisible to the rats. Invisibility was the first step. Then he began to feed them. At first, they thought him strange but then became offended when he failed to bring them food. Then gradually he acquired the right smeli and even began to feel a sort of telepathic connection with the little creatures. Once dawn in the cellar, he began to weep out of sheer beredom and despair. A fat rat brought him a bit of cheese. It placed it right in frent of him. In that instance, Franci became aware of astrange and marvelous thing: he knew that he would never be lonely again.