II. FACE OF THE SOUL – Good and Evil

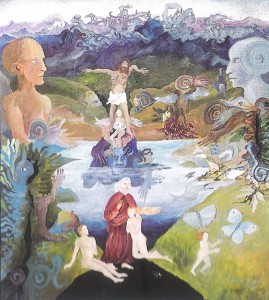

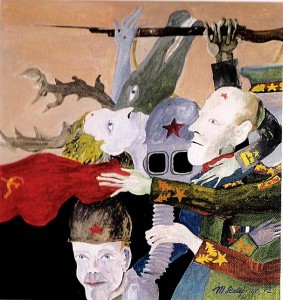

Maksim Sedej ml.: Kompozicija VII, olje na platnu 130×130 cm 1964

Maksim Sedej yr.: Composition VII, oil on canvas 130×130 cm 1964

The River in the City was diverted through a deep concrete channel so that its watery flow was almost invisible. In spring when the snow melted in distant hills or after a strong spell of autumn showers, it filled its bed to almost the halfway mark and soundlessly rushed through the City. Uprooted trees and broken branches floated on it like a fleet of ships after a lost battle. The smooth concrete walls of the vertical banks prevented the trees and branches from getting caught and disturbing the flow of the water so there was very little sound as the river passed through. In summer and winter, the shallow water crept slowly, hardly perceptibly, along the bottom of the river bed.

The high city houses were separated from the water by a narrow gap and protected with a concrete barrier.

The gap almost had the status of a town street though in places it was so narrow that terraces, hanging like balconies over the water, had been constructed above the river. These terraces or balconies provided the best vantage point for the events that took place on the River. The river bottom was reinforced with large square cobblestones. Scarce river moss grew in the crevices where the stones met, lending the water a greenish nuance. The River gently curved and the cobblestones ended just under the balcony beneath our house. From that point on, the River flowed along a smooth concrete bottom. On the opposite bank about ammeter above the River’s surface, there was a big oval culvert and a stream of water gushed out of it. The stream came from channels far beneath the City and its force was great enough to push the calm waters away from the curve of the river, creating a sandbank under the balcony where thick moss grew. When the river was shallow, alittie mossy island a few meters long jutted up above the surface. At the end of the little island, I could just make out the beginning of the concrete bottom where the water got a little deeper. Long mossy fronds undulated on the surface making a green roof, an ideal hiding place for the fish that darted up from the smooth concrete bottom. I had to be extremely cautious if I wanted to surprise the fish. As soon as I climbed the concrete barrier, the fish had already spotted me and fled in panic. The smaller ones hid beneath the moss and the larger ones disappeared down toward the riverbed into deeper water. Sometimes a big one would hide beneath the mossy fronds, giving me the opportunity to catch it with my hands. Not far from the island, iron ladders led down to the water’s surface.

ln those days, an uneasy silence prevailed over the City. Only the creaking wheels of military vehicles or farmer’s carriages broke the silence, by the clip-clopping of the hooves of tired horses that could barely keep their balance on the granite paving stones of the City’s main thoroughfare. The road led down from the distance hills and, along it, columns of defeated armies and frighten ed people, heads bent low, slowly made their way through the City. This nearly silent, slithering procession of human despair was interrupted only occasionally by the wail of a baby which al so soon subsided.

I didn’t see any fish when I looked down into the water. I glanced quickly up and down the River and it seemed to me that something had moved or that someone was watching me. A curtain on a window on the other side of the River swayed slightly. There was never any sign of life behind that window in the deserted house except when something extraordinary happened in the City. I had a feeling that something was terribly wrong with the fish so I climbed up on to the concrete wall and looked underneath the balcony.

Something seized me violently in my chest. It was the same as the time I heard about the poet’s death. A little girl was Iying on her back on the mossy green island. In an instant, I took in every detail of her. She wore a silk blouse with patterned ribbons, she had a colorful neckerchief with little Eiffel Towers printed on it. She had on a pretty dark brown velvet skirt. Ught gray daisies were carefully woven into her white socks woven from the finest thread. On her feet were patent leather shoes with thin straps and big silver buckles. And her hair had been braided in two beautiful plaits and tied together with a great red ribbon which had sunk into the moss. Yet I couldn’t have made out all those details so quickly from where I hid under the balcony; the picture of the girl was already inside of me.

I remember well the day I first saw her. It had been a religious holiday. There had been staIIs filled with the most wonderful things all around the church and in the square in front of it. The bells had chimed cheerfully and had boomed solemnly. And the crowd milling around the staIIs had poured into the church and into the pubs and then returned to the square again. I watched the flowing crowd from behind a decorated bush at the lower end of the square. There was no good reason for observing the milling circling crowd for such a long time but something held me back so I remained in my post. Then I saw her. She was wearing the very same clothes. She fluttered towards me like a butterfly, vanished in the crowd, then’ appeared and vanished again. She was like one of the big brown peacock butterflies flying and playing among the rare plants in the deserted monastery garden that I could watch for hours and hours. Her beautiful appearance overwhelmed me so much that I wanted to see her from up close. I slipped into the crowd and it carried me away; I began to flow with the river of people. It was impossible to find anyone in that crowd. When I had given up any idea of finding her again and only wanted to corkscrew my way back to freedom, she suddenly appeared right in front of me. Her presence confused me so much that I blushed. Only then did I notice that the girl was holding the hand of a tall pretty lady who looked an awful lot like my own mother. The two laid eyes on me at once; they must have seen me standing behind the bush, secretly watching the festive movement of the people. The pretty lady asked me what my name was and if I wanted to have my photo taken together with the girl. I couldn’t rid myself of an awkward feeling of embarrassment so I simply nod dad and kept my eyes fixed to the ground. It was then that I noticed the pretty grayish daisies woven into her white socks and the big silver buckles on her patent leather shoes. The beautiful lady left us alone for a moment; the girl took my hand and gently squeezed it. The lady brought a big Easter bundle decorated with fancy ribbons, candies and a wonderful bright red orange. She led us to a place in front of the church stairs which were empty right then. She placed the bundle into my hands and stood the girl beside me. She took a camera from her handbag and took a few pictures. When I heard the snapping of the camera, my timidity vanished as quickly as it had appeared. I looked the girl in her eyes and saw the azure sky reflected in them. Right in that instant, a raging man wearing the uniform of a foreign officer rushed between us. He said some harsh words in a foreign language, grabbed the beautiful lady’s hand and pulled her towards a car waiting at the edge of the square. The girl began to cry and ran after them. But she stopped in front of the car, turned back to me and waved her hand. The big black car disappeared and the reflection of the azure sky with it. Without giving a second thought to the delicious orange, I gave the whole bundle they had left behind to Franci who had observed the whole thing and shrewdly detected my stunned bewilderment.

For a long time after that incident, I used to wander around the square and the church, waiting for her to appear. But she never did. Never again. One day I received a letter with the photo taken by the pretty lady. On the back of the picture, she had written that they both sent their warmest regards and hoped there would soon be another holiday.

I don’t know how long I numbly stared at the stiffened girl before I felt them: the presence of all those strange inhabitants of the old town houses, the lofts and the cellars. I have no idea where they came from. But they smelled a disaster; they felt it. A certain agitation seized them and they came to the precise place where evil! had occurred. Thus they saw everything; they knew everything. They see med to take no interest in the procession of death that wended its way through the town – but that was only the appearance they gave. For anything thrown away or left beside the roadside by the fleeing columns disappeared overnight. Everything, included deserted cannons. They shoved me away from the fence when they came. A big crowd gathered: from children to toothless old people who could only wag their fingers and point at the sky. I had only begun to notice such people when we moved to this part of town. I saw them in the morning, at the beginning of day. Dawn is special in the old part of the City. The narrow streets are still dark, illuminated only by dim street lamps and the sky glows an extraordinary sea blue above the rooftops. But when the sun actually rises, everything – sky, lanes, and houses – becomes gray. once the foreign soldiers, guns tipped with bayonets, had gathered a group of people at the crossroads near the former penitentiary. There was plenty of space there. They herded us together over the course of several hours. It was freezing cold and we all stamped our feet and waited, uncertain what would happen to us. Nobody knew why we had been crowded into that place. But I was filled with surprised when I looked at the strange people around me. I never saw the majority of them again. I got goose bumps when I realized that most of them would simply squeeze into some narrow space where they would wither away. The Houses in the City weren’t attached and there was a good meter gap between them. These gaps were walled up on the street side and they faded into the grayness of the city streets. Many people lived in those gaps. Perhaps that’s why some of them seemed so flat to me: some seemed oddly pointed and others barely reached the height of five feet. Some had heads covered with thin wispy hair. While I gazed at them in astonishment, my father poked me and whispered that the soldiers were looking for criminals. It was then that I really noticed how odd my father, mother and two brothers looked in that crowd. The soldiers had dragged us from the bed where we all warmed ourselves in the cold winter season when we didn’t have enough fuel. We wore nightgowns that were a little too big for us and my father had pajamas made from the same flowery patterned cloth. My mother had sewn these night clothes for us and we looked like a big bunch of daisies in the middle of winter. The next day the carpenter kindly told my mother this funny metaphor but at the time we just huddled together and shivered with cold.

Suddenly the crowd roared and rushed. A short chubby man had spotted a figure high on a roof behind a chimney and yelled, “The band it is up there! Look!” The crowd swelled with excitement and the soldier pressed the onlookers against the walls with their bayonets. Then the crowd cal med down and the soldiers broke into the nearby houses and soon appeared on the roof of the house where the man was hiding behind the chimney.

There were the sound of two ban gs on the roofs and then shards of roof tiles fell to the street. Everything became quiet. After the passage of a few minutes that seemed as long as eternity, the entrance door opened and the soldiers pushed out a man bound with barbed wire. He was covered with blood so his face could neither be seen or recognized. “Kill the bandit!” a littie man yelled, spitting in the direction of the bloodied man. The soldier who was guarding the crowd approached the little man, pushed him aside and growled at him in a harsh voice. Later my father told me that the soldier had disgraced the little man. He said that to wish such a thing on a fellow citizen is doubly brutal.

The criminal was dragged away. The crowd dispersed into the narrow lanes and vanished. I noticed that something had fallen from the bleeding man. I was the only one who noticed it. When everybody was gone, I went back and picked up the things. They were two steel teeth and a white piece of bone.

I knew that even my mother would not be able to help the dead girl so I went to the deserted monastery garden. My mother was usually able to calm me, to make the worst things bearable. I always tried to avoid’ her when I had been naughty but it never worked out. She could read my mind. Often when I believed that some infraction had been long forgotten, she sat me down at the table and told me calmly and kindly how I must behave the next time. Sometimes I wished she would just slap my face. I’d be offended, I’d feel punished but at least the sin would be paid for. But she never slapped me!

The deserted monastery garden was my own secret place that nobody else knew about. A high wall that did not pose a serious obstacle for me surrounded the garden. I climbed to the top of it on a beech tree and then stepped to a wonderful tree that grew within the garden, close to the wall. It had beautiful bluish-red flowers that looked like tulips; that’s why it was sometimes called a tulip tree. It looked magnificent in the spring time when it was covered with clusters of blossoms. The tree had wide branches so it wasn’t difficult at all descending to the garden. The garden itself was thickly overgrown with rare grasses and plants that could be found nowhere else that I knew of. And huge trees grew among them. Plane trees. For me, the most mysterious part of the garden were the stairs leading down to a semi-circular opening that was covered by a thick iron grid.

Sometimes I peeked through the grid and my eyes traveled along corridors that disappeared into the darkness. The dim sounds I could make out within, like the dripping of water from the walls, made the place seem even more mysterious. Sometimes I sat on a thick branch and watched the bugs and butterflies flying over the grass. One day I al most fell off the branch because I saw something black slipping through the grid and slowly crawling up the stairs. But I wasn’t frightened for long. The black apparition wasn’t big and it looked quite a bit like an ordinary cat. I carefully approached and surprised the animal. When it saw me it turned, horrified, and ran back down the stairs and through the grid. I ran after it and just managed to see what was wrong with it. It was a cat. Its back legs were lame and it only moved its front paws as it rushed down the stairs, dragging its body and lame rear paws behind it. It had a littie long hairy stump instead of a tail. From that day on, I always brought the cat leftovers from our means. The first day I brought the food, I waited impatiently for the poor little animal to appear but it never did. The next day, however, the food was gone. This went on through the spring. The lame animal obviously ate at night and I soon lost any hope of seeing it again. One day when I was putting the food in the usual place, I sensed a black shape in the darkness of the grid. I hid behind a huge plane tree and waited. After a couple of hours, I finally gave up. As I climbed up the ‘tree on the wall, I glanced back toward the garden. From behind the last stair, I saw the little black head of the cat watching me. We looked at each other for a long time and then the cat seized the food and disappeared. From then on it was always like that. I put the food on the top stair, climbed the tree, and waited a moment or two for the little black head to appear. The cat and I looked at each other for some time, then he grasped the food and crawled down to the grid and disappeared into the blackness of the hole. I found a certain satisfaction in this relationship. The idea of caressing his silky fur and his lame little body actually filled me with slight horror. I knew if the lame cat was found byanyone else, they would kill it. It would be do ne in secret and I would never know who did it. That was how Death’ was in the City. At certain times, its deeds were revealed in all their terror and then the presence of Death retreated once again into silence and mystery.

But there was one time when I surprised death. The mysterious deserted house opposite “my” balcony drew my attention, making me wonder: just what was going on down by the River. I decided to explore. But I found it impossible to break into the house. lron crosses protected the cellar

windows; the windows on the ground floor had been covered over with planks, firmly nailed down. All the entrances from neighboring houses were walled up. The roof seemed impenetrable too, everything battened down with thick planks. The massive front door was locked with a special lock. Miro, the shoemaker, solved the problem for me. When I my confided my wish to him, he seemed upset at first but then his face cleared. “There is a locksmith who owes me a favor so 1’11 be able to give you some very special keys. If you’re caught, toss them in the river so that the fellow who lends me the keys won’t be wrongly accused of the crime. And once you’re in the house, you mustn’t touch or take anything. lam actually very interested in it myself. Perhaps it’s under a spell. And remember, you don’t know me.”

I waited for curfew and sneaked out. It was already dark and the sky above the City had become a deep blue. It was almost too easy. I unlocked the door with my second attempt. I carefully closed the door behind me and cautiously peeked around the obscures place. At the top of the staircase, I saw a window covered with a dusty curtain. I moved it aside and beheld the most beautiful scene. The City was drowning in the dark blue sea of the sky; the windows glowed in the scarlet of the sunset; purple light filled the streets. “My” balcony on the other side of the River was right before me. It was swarming with soldiers in greenish uniforms. They climbed on the fence along si de the River. They were running along the bank, waving their arms and guns, shouting. So I looked down into the River and saw. At first I didn’t understand what I was seeing but then I realized with terror that there were corpses in the river. Two or three tied together, blown up like balloons, floating down the river. The bound clusters collided with one another, bumping each other aside, hitting the slippery bank where they turned and continued floating down the river with their heads or feet first. I stili remember how frightened I was when I ran home. The next day I heard that some time ago, people had been killed in the woods, tied with barbed wire, weighted down with stones and thrown into the river. When they finally came up, their bodies were bloated like balloons and thus they floated down on the surface of the water.

The war ended a few days after the little girl’s death. Her death must have been somehow connected with the end of the war. Foreign armies fled. and other foreign armies came. They spoke astrange language too but it was easier to understand. The policemen remained more or less the same. The same policeman who had pursued me in vain for fishing during the war now threatened me with a gun. From then on I went fishing in the big culvert that meandered under the City. If by some strange chance an elephant were to get lost in that labyrinth, it would never be found. That autumn when beautiful red leaves fell from the huge maple in Town Square, my mother was waiting for me in the front of our door. She held in her hands a basket covered with a napkin and something stirred beneath the napkin. My mothers hair practically stood on end because she was afraid of animals but, despite that, she pulled the cloth aside and revealed a beautiful little black cat in the basket. I thanked her politely but already sensed what had happened which she must have already known. Without even looking at the animal in the basket, I rushed to the secret monastery garden.

All over the City buildings were being pulled down and new ones were being built. The monastery and its garden were among the first to go. They pulled down a part of the wall, dug up the garden and made a big hole in the wall on the opposite side of the garden. Then they continued to dig. They laid hollow concrete pipes. There was a giant heap of spare pipes in the garden and that was where the workers ate lunch every day. The cat discovered this and ate the crumbs they left behind every day. One day they returned unexpectedly and surprised the cat. Frightened, it scrambled into one of the pipes. The workers stood at the pipe’s two ends to prevent the cat from escaping. A member of the group tore a large branch off a plane and thrust it into the pipe. The cat jumped out in panic. They killed it with the granite blocks they used to support the pipes in the ditch.

I can’t say that I was surprised when I rushed to the monastery garden and saw the little lump of red flesh and black fur because I’d been expecting something like this for some time. Everything had pointed in that direction. The workers’ behavior hadn’t augured well. They had devastated the garden, broken and uprooted the beautiful flowering bushes and the smaller trees for no reason. They had stomped over plants and flowers and desecrated” every comer of the garden so that instead of with flowers it was sprinkled with tom and dirty pieces of paper printed with black letters and red stars. With their heavy boots, they crushed the stone edges of the stairs carved in the Baroque era. They ripped off the grids protecting the entrance and broke the water pipe so that the water streamed into that infinitely mysterious interior. The smell of decay already floated above the place.

I was terribly angry, filled with indignation. Everyday I went and sat on the monastery wall. I systematically studied the workers’ habits hoping to think up some cruel revenge. Then one day the following story played out. The workers were drinking the contents of a bottle of brandy someone had “forgotten” on the pipes. Afterwards they went, shouting and roaring with laughter, to a pub to continue drinking. In the pub, Miro treated them to another bottle of brandy – bought with my savings – and then left. From where I sat on the wall, I could see almost all the rooms in the pub while a beech tree concealed the view of me from the pub. I watched their wide-open mouths, gulping brandy, guffawing or smugly whispering. I al so watched the waitress who served the merry company, smiling cheerfully all the while. Suddenly she disappeared and I felt a tremor of excitement as if I was waiting for the beginning of agame. Tensely, I watched the window opposite the pub door and felt a great satisfaction when I finally saw the waitress. She approached the telephone cabinet, looked around surreptitiously and placed a GalI. I had the fleeting desire to run to the pub as I usually did and warn the collected company but my rage was stili too great. I concentrated on the image of the crushed cat’s flesh. But then I couldn’t stand it any longer. I

jumped from the wall and ran towards the pub. But it was too late. The police had co me faster then they ever had before. They rushed into the pub, snatched the workers, yelled at them and pulled two of them from the group. They threw something into the face of the first and then beat him to the ground with clubs. They chained the other. Two police men seized another worker who was resisting. Each grabbed a foot each and thus they dragged him to the police station. At first, he writhed and twisted but then he cal med himself and used both hands to protect his head as it bump against the ground. Something white and bloody fell from him but this time I didn’t pick it up.

That was when I finally understood my mother who had never beaten me when I did something unpleasant or naughty. instead , she kindly and lovingly explained to me how I should behave the next time. She probably thought that would be the easiest way to spare me pain and, perhaps even more, to spare herself pain. For no beating or punishment will release you from what you did out of hatred, stupidity, envy, self-conceit or ignorance. Although Miro, the shoemaker, comforted me by saying that he hadn’t expected such a denouement, I feel ashamed to this very day.

I didn’t randomly choose the events from my youth I wanted to tell about. Indeed, I think I chose events from my life that did not favor love, grace or forgiveness, poetry or faith. Yet these events are deeply connected with the secrets of being and of Creation, which I must have subconsciously understood even in those years.

I could never imagine God as a Being living in the vastness of the universe, a Being who from a suitable distance controlled, directed or merely observed what was happening. So I have never been able to understand people who even today see k God in this vastness. I didn’t understand them back then and I don’t understand them today. God is present everywhere. In all dimensions. Back then I already had a feeling that God is both cosmic and trans-cosmic.

I have also understood for a long time now that God is not only infinitely loving and understanding but that He also possesses an infinite sense of humor. Whenever I vainly asked God to give me a sign of His presence in those days, I would experience Creation, nature, people and the things all around me with a total openness oft he soul, with the utmost admiration and affection, with a passion and an understanding of mystery. Here I would also like to say that I was critical toward things and deeds, which were not in accord with my own conscience, a growing conscience I instinctively cultivated. The intensity of these feelings and experiences,. especially the tragic ones, gave me the foundation and the breadth to be able to accept everyone. Back then and stili today. From the people on the margins of society – almost non-persons – to the greatest people who though sometimes humble in their needs and potential penetrated through to the transparent truth of this world. As I did right along with them, slowly, though critical dialogue. Mystery inevitably vanishes into the deepest darkest depths of truth, a truth that cannot be delineated by mere walls. The moment you erect a wall or even sense one, you are lost. The poet, Dane Zajc, described it this way: “This is the first and real death of a poet; the death of his body is only a formality.” There are limits set for man, limits that nevertheless crumble into the darkness of transparent truth. These limits cannot be described as mere walls. Good and evil cannot be taught by means of a ruler or secular laws; the difference between good and eviI exists in the opaque depths of man, in his soul, in his very origin. And these depths can only be iIIuminated by God and by love for nothing, by love given freely, by active love. Because evil is something spiritual. Although I intend to leave open the possibility of dual explanation of the soul at the end of these reflections, I think it is necessary to look at the foundation of doubt to arrive at a final understanding and explanation of the soul. The opinion of many individuals and of many great thinkers is that the soul and the body are the unrepeatable essence of man’s personality and cannot be divided from each other. They are a unique gift from Nature or God, a gift which ceases to exist with human death. The ancient Greeks connected this uniqueness of spirit and body with the cosmic order but also believed that the soul ultimately escapes from the body.

However, the effort to understand the immortal soul stems from the very beginning of incarnation, that is from the times when man realized the difference between good and evil and was, as a result, expelled from Eden. Faith in the eternal soul that first emerges or ignites into life in the human embryo floating in the ocean of the mother and only leaves the human being when the body biologically dies, is the foundation of our faith and hope. Herein lies the difference between the material universe which is transitory and the spiritual universe which is eternal.

I would like to illuminate the problem of the soul from the standpoint of my own artistic and conceptual nature, from the dimension of my own reason and experience. Therefore, I must first ask some questions connected with my understanding of and doubts about the eternity of the soul. And I must ask these questions on a certain level of perception.

The question of the soul is essentially the question of eternity. And questions about eternity are asked about and limited to death. That means that the (physical) death of the body and the soul are on a certain level asymmetrical. They don’t correspond to the notion of eternity; the experience of life is by definition limited by death. Everything in the Nature of Adam is transitory and ephemeral. Active love is the only thing that surpasses the instincts of the man-animal and reaches toward eternity. But this is onlyahope, an agreement – pretty much unilateral – which man made with the eternity of nature, that is with God.

Adam not only conceptualized the distinction between good and evil, but he also recognized the might of Creation and the power of Nature. He knew that the darkness behind which the charming Nature of the day hid represented the Other, .the even mightier entity in the night sky. It represented the infinite side of the same Nature in which he lived. Adam soon understood that he was the only living being to whom the mighty powers of Nature had revealed Creation. This awareness of the self, the consciousness of a being who can see with his inner eye: this is the fate of Adam and our own fate. Indeed, this inner eye is the origin of man, the origin of the soul. The beginning of man’s consciousness and his conscience mind is this fatal and mysterious feature. Without it, the answer to the question – who is man? – can only be expressed in the outward form of man and his existence.

Man submitted to this mighty force, to this vision of nature and he dropped to his knees before it. He felt the divine nature of creation and eternity. Love and awe acquired different dimensions and, not only those that promote the existence of the species, the human race. Along with the development of this active love towards fellow-man and towards Nature, man also developed the spiritual opposite of love – evil. Cain and Abel are our destiny as well.

It is possible that the idea of the immortal soul emerges precisely from the notion and conceptualization of the special role of man in Nature. Death doesn’t sever our bonds with loved ones when they die because their spiritual presence remains alive in our souis. Reaching eternity, connection with the Divine, is our only hope. It alane gives a higher purpose to life and to love, both of which are so beautiful as to sometimes seem fatally tragic. Man soon discovered that he could not attain the infinity and eternity of Nature with his mortal body or with his spirit or his soul.

It probably didn’t take long before his inner eye met the eye of the Creator, that is, of God. And thus we can begin to look for the first trace of man’s origins.

Here I need to pose another important question regarding the soul: What is truth and how it is possible to recognize or anticipate it? Is truth something finite that retreats into the most opaque depths of man’s purpose? The question of the soul is also the question of truth and man has forged many pathways to truth.

I would also like to point out the interdependency of process and force in the universe which together prevent chaos and unpredictability and, left on their own, create the relationships within the universe and the growth (lnclination) of the universe. Similarly, the interdependency of (flesh) man-animal and (spiritual) man facilitates the process of truth. Man wants to know the essence of Nature – both its material and spiritual essence – because there exists in man the unending desire to pluck the apple of eternity. Saint Paul already reflected on the four ways to arrive at an understanding of truth. Later in the history of thought and even today, wise men and scholars recognize these four threads that lead to the understanding of truth. This whole method of thinking tries to find traces of these threads that lead to the Knot of truth. They ask the question – What is truth? – but do not answer the question. The truth can only be declared by God. This essential wisdom can be traced to the times when man was stili a spontaneous part of nature, left to the blind forces and fullness of his own passions, fears and life. Thus I arrive at the third question of the soul: To what measure are we permeated with and committed to primeval Nature with which our most distant ancestors existed in perfect harmony? To what degree do we possess love for Creation and to what degree do we possess irresponsibility for Creation? How much of this primeval ease and love, competition and struggle to continue the species stili exists within each of us? The great Johann W. Goethe was one of the first who sought to understand the story of Adam. He explored and studied the primitive jawbone, distinctions in which were supposed to account for the difference between Adam and the animals. He arrived at an understanding as to why modern man no longer has this bone. He discovered that in the course of man’s evolution, the bone atrophied and the jaw closed. Goethe believed, as did Leclerc before him, that Man is in fact an animal. Science also began to slowly distinguish mythological heritage from scientific truth. Adam had evolved in a way that ultimately drove him from the harmonious rules of nature and thus separated him from animals. He developed a creative brain (the neocortex dominates here) and, with it, an awareness of himself, his neighbors, of beautiful nature and the sky, especially the night sky into which he seemed to sink and melt. He began to observe and admire the nature that had co-created him over the course of millions of years. He experienced the miracle called Creation. It is said that the human animal exists beneath this cortex. Certainly, it would exist with out the cortex. All that lives emerges from the miracle of transforming dead matter into living matter. All that lives was created in the time when the red-hot fiery globe began to cool. Perhaps a comet or an asteroid from the universe brought the seed of life to earth and all living beings on the Earth are thus connected with this ancient life. But ancient life evolved in many different directions. The most wonderful creatures lived in the roots of the human tree: the gentie and tender white gibbon and our common ancestor who lived 25 million years ago on the island of Rufus.

And, of course, there are other less pleasant beings in man, beings whose essence are decanted from remote times into the present.

ln the darkness of his subconscious – traces of which lead back to the coming to life of dead matter – man searches for a freedom unencumbered by the moral standards of civilization, the freedom where the pure source of human existence with Nature is presumed to reside. Man searches in pre-civilization, in the times before even families were formed. In the times when he was entirely committed to earthly nature. Back then, the night sky represented only darkness and danger. Night was the time for predators. The time for nightmares Jhat penetrate the darkness no matter how dark it may be. A darkness in which it is impossible to hide. fy1an, trapped as he is in the norms of family and civilization, is often obsessed with the ease and freedom of animals. But there is no true freedom anywhere in nature; rules and laws are strictly defined in herds of animals, in hives and other groups and creatures that transgress these laws are eliminated. There is no less unfortunate being than an animal or a man who is ostracized from its community. Even the mighty lion is destined to a horrible death if he has been defeated by his rivals and exiled from the pride. He will either die of hunger or be mercifully exterminated by hyenas. A few of nature’s creatures may exist in total freedom but they represent humanity’s most frightening nightmares. And perhaps even these creatures are too preoccupied with killing to be truly free.

The subconscious reaches towards the origins of incarnation, towards the instinct for survival, love and primeval fear, the unity of Nature and finally towards a conscious understanding of Nature. Back to the time when man transferred his creative energy from tools and objects of survival to spiritual values, the burial of loved ones, leaving on the walls and in the depths of subterranean caves a physical trace of his spiritual presence. Today the presence of this Other stili exists in us. The presence of Otherness as well.

Purity, which was the basis on which Adam conceived his pri mary understanding of the world and of Nature, represents the artist’s connection with the very foundation of all human understanding. Rudolph Arnheim thinks that these pure ancient features are preserved in the depths of the human mind, that they are both irreplaceable and absolutely necessary.

The belief, however, that elementary cognition and images of reality are the one true essence of real art leads inevitably to primitivist aesthetics which can not contain the refinement of the human mind and its output. Because art as the expression of amature personality is never simple; it can not necessarily be reduced to the simplicity of the undeveloped mind. The apparent simplicity of the essence of a genuine masterpiece is just as deceitful as the apparent essence of a truly simple artistic product.

The cult of the subconscious in art is one of the most dangerous substitutes for real depth in genuine creation.

According to Arnheim, there is no reason to believe that the deepest wisdom exists only in the most secret parts of the subconscious. Wisdom must emerge from the harmonized efforts of all layers of the mind, from its peculiarity and its refinement. The prototype of art is not, in fact, the stony colossus at Easter Islands; it is rather the connection between what is elemental and the perfection we find on the walls of Lescaux, Altamira, on Cezanne’s canvases or in the statues of Henry Moore.

The fourth question of the soul demands the question of faith: What is faith that binds together and brings sense to all questions of the soul? The question of faith is the question of good and evil as well. Faith is divine grace; it is our salvation from nothingness. Good and evil exist in human understanding and conceptualization of Nature. Therefore in order to con sider good and evil, it is first necessary to explore the possibility that these two features be long in the dualistic structure of the Universe Le. in the very nature of the Universe. Many thinkers and scholars prefer to insist on the indifference of the universe to such trivia as the destiny of mankind or even to the (singular) death of our whole galaxy in a Black hole.

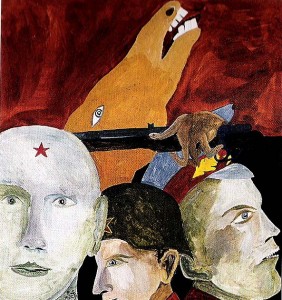

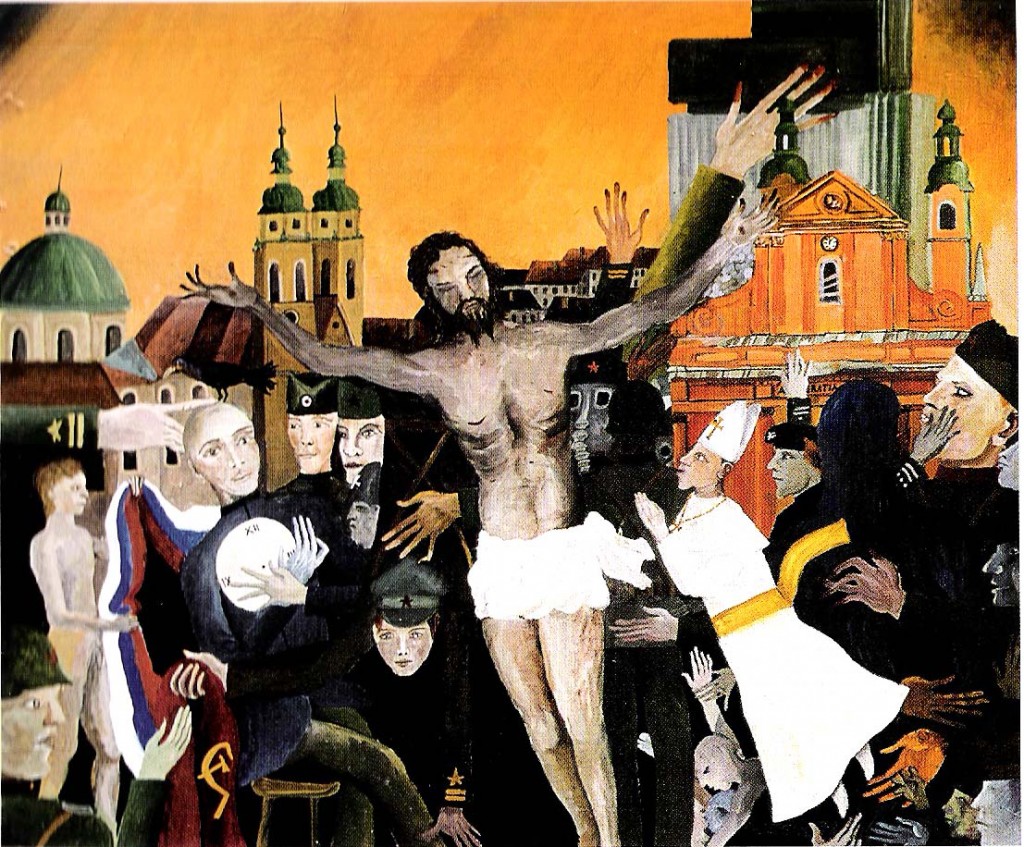

Maksim Sedej ml.: O dobrem in zlem I. variacije na sliko V. Carpaccia

Olje in rempera na lesu 100×100 cm, 1965

Yet good and evil enable us to conceptualize creation in other possible civilizations that may emerge in the endless space of the universe. They al so enable us to conceptualize creation on another level in our own conscious life. Good and evil can only exist at the highest possible level of awareness because they are basically a product of conscience. Good and evil are thus of spiritual origin. There is a great deal of evidence that these two traits or features of everyday life intermingle and transform themselves in asimilar way as subatomic particles, that is in accordance with Heisenberg’s principle of indeterminacy. In other words, their interaction does not take place simply for cosmic reasons but because of laws, customs and the spiritual dimensions that are the forces behind the civilizing process of mankind and of individual human communities. Good and evil appear differently in the various communities to which individuals belong. Individual human communities consciously or randomly plan the strategies of their survival and evolution regardless of the means and deeds by which they attain these goals. Good and evi I intermingle and exchange in direct proportion to the efficacy of the deeds that ensure the level of prosperity and vitality of individual human communities. Today’s modern scientific society already places itself “beyond good-and evil”. In other words, it establishes secular laws that make society possible regardless of the conscience of individuals. Yet the question of the conscience is the essential question of good and evil precisely because of the relationship between the individual and society. Conscience and faith are the private domain and right of each individual and so they must never be manipulated on behalf of “higher causes” or various ideologies. Soon after Taras and I experienced the storm in my little valley and the apparition of the church outlined with helium light, I made two paintings. Both were closely connected with my attitude to good and evil. The first one, Of Good and Evil, a variation on Carpaccio, was conceived as a triptych. In the middle there were two oblong paintings: at the top was a copy of Carpaccio’s Saint George and the Dragon, and at the bottom, a replica of the top painting but populated with figures that I had discovered and painted before. The side panels were compositions that logically complemented the two in the middle. The second painting was a pentaptych. *

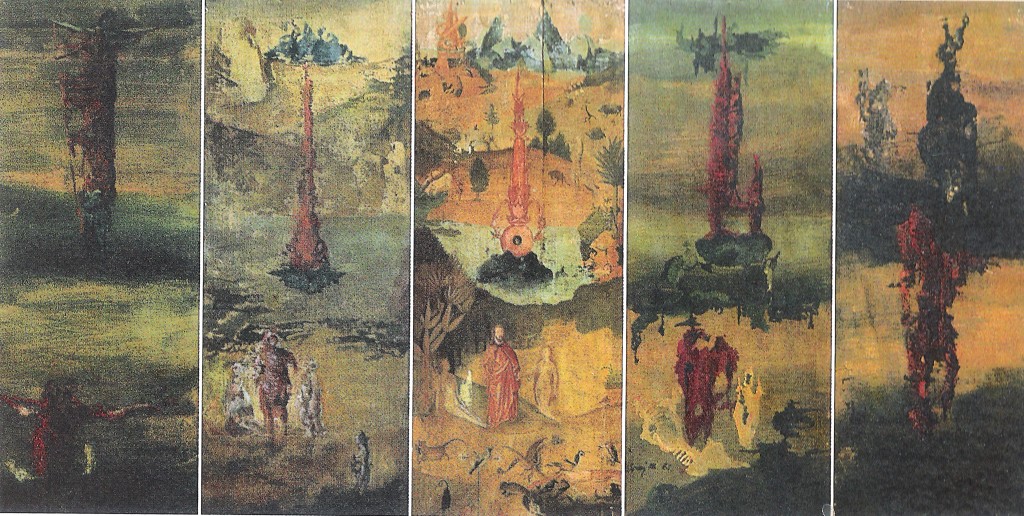

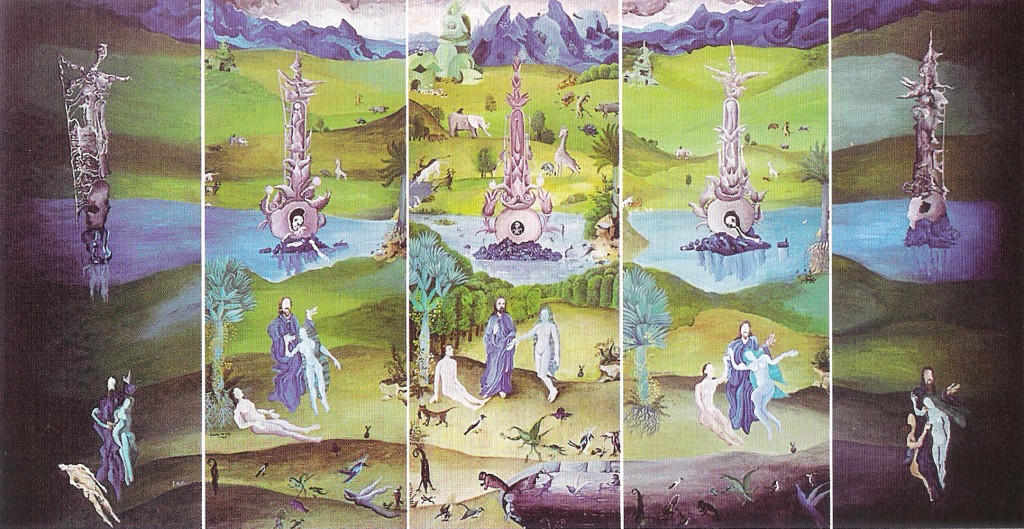

ln the center, I painted a copy of Bosch’s Creation of Eve and the side paintings represented adecomposition of the central painting. At both edges, the painting sinks into the darkness of Ancient Nothingness so lentitled the composition: The Desert Grows.

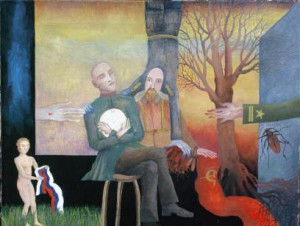

Maksim Sedej ml.: Puščava raste I. variacija na sliko Stvarjenje Eve H, Boscha

Olje in tempera na panelni plošči, 120×200 cm, 1965

Both Carpaccio’s and Bosch’s paintings are closely connected with concepts of good and evi!. In Carpaccio’s painting, Saint George defeats the dragon (evil). The painting is both utopian and symbolic because it depicts the destruction of evil. Evi I must be killed or destroyed so that mankind will be saved from evil and will be able to maintain the purity (virginity) of our relationship to Creation.

Maksim Sedej ml.: Puščava raste II. variacija na sliko H. Boscha: Stvarjenje Eve

Olje in tempera na panelni plošči, 100×200 cm, 1965

The painting depicts that instant when the spear of the knight in armor, mounted on his horse, penetrates the dragon’s gullet. In that precise instant, evil is not yet dead. (This could be compared to Freud’s analysis of the hand movement of Michelangelo’s Moses.) The spear has not yet punctured the dragon’s gullet and the dragon stili stands firm, ready to attack. Evil is not yet definitively defeated and eliminated. The townsfolk knew precisely what it meant to defeat “evil” in the City and, as we know from history, they did it frequently enough in those days. There is no anticipation in the painting of the end of the world or of the Last Judgement day. The townsfolk observe Saint George’s performance from the balconies of the palace. Some of them promenade along the coast of the Piran bay, presumably running errands of some sort. The town is surrounded by walls and fortresses and is thus protected from the evil without.

The great fortress doors leading into the town are thrown open. My father had a reproduction of this painting exhibited in his bookcase and I have always been strangely attracted to it. Contests of knights and dragons, which as a child I drew again and again, made a mighty impression on me. Father had many reproductions of Saint George, the principal one being Rafael’s depiction of the saint but I was only interested in and ultimately convinced by Carpaccio’s depiction. I discovered the mystics in it, had the same feeling looking into it as I did looking from my little valley at the distance city lights glittering in the night sky. Above, there was the galaxy covering the firmament, countless bright lights and remote stars and beyond, the infinity of the Barje mist.

I must admit that the apparition of the church confused me so much that I must have repressed it into my subconscious. It certainly did not cause me to run immediately into a church to give myself to prayer. I understood the sign in my own way and I slowly harmonized it in the mili of my subconscious mind, blended it into the way I saw and sensed the world. God was something totally incomprehensible and unimaginable for me. The Church, on the other hand, was something entirely different. It was a clear easy path to God, much clearer and easier to imagine than the God and creation of my own heart. The Church was the opposite of science; it learned and taught from the greatest poetic work created in this world: from the Holy Bible. No poetry, however, can be completely explained by reason. One can only experience it in the synthesis (the poet Dane Zajc would say: in the symmetry) of the refinement of the spirit and the refinement of the mind.

The first thing I remember being fully aware of was the fact that I lived in times which were a mixture of good and evil. Sometimes the two seemed to be inseparably connected and at other times they stood on opposite poles, in judgment and mutual recognition.

The general situation in those days was so grotesque and tragic that in my later painterly analysis of good and evil, I discovered that I must first identify and define these two human features in accordance with the environment in which I had lived. Only afterwards would I be able to establish a critical attitude towards, on the one hand, the meaning of good and evil in a totalitarian system and, on the other hand, towards the problem of conscience and the difference between spiritual good and evil. Of course, this was only one part of my experience; the other part of my thinking at that time was so intimately linked to the transcendental that it didn’t permit submergence into a rational critique of “all that exists”. I tried to unite these two attitudes in the development of my work and later to even build on them. But in that initial period, I developed the foundation for all my later cycles of paintings which, united, represent a whole. While studying in these of ten very contradictory modes, I finally did construct my attitude towards “all that exists”. I do not intend to analyze or even present in this book all the creative output that resulted from this experiment. But as far as my painting was concerned, I didn’t get much help from it only the certain knowledge that criticizing “all that exists” is a futile exercise and would lead me nowhere. At the time however, it was the only thing that could take me close to the edge, to the nothingness that is one of the many dimensions of poetics and paradoxically of “all that exists”. Thus, it was an extremely important experience in my development as an artist.

The intellectualization of painting is part of the technical and scientific breakthrough into contemporary art. This alone would not be such a bad thing if it were in equilibrium with the poetic side of creation. It may sound extremely strange but I believe that the majority of contemporary painting and other artistic production is explicitly naturalistic and is connected with daily political and cultural events and with the scientific truths that are ceaselessly being discovered in our era. That is, with history itself. Yet the poetic aspect of artistic creation surpasses the limits of this perspective and is itself an integral part of “all that exists”. Only outstanding artists succeed in creating a vision of the whole. Poetics and technological development have their common points that can be mitigated and brought into harmony. These common points comprise various nuances from the excitement about human, scientific and technical achievements to doubts about the new man in the scientific epoch, an entity which is becoming more and more redundant and may one day be replaced – at least in art and poetics – by cyber-engineers, by the virtual intelligence of contemporary computers and by the so-called culture industry. In terms of business, it is based more and more on the production of artifacts which at the same time cunningly suggests the notion that the era of artifacts in art and poetics has essentially ended with the development of cyber-technology.

There are only two things that transcend any social situation; the first is the conscience and the second is the awareness of Creation among Christians who profess faith in God and the Gospel.

ln a totalitarian system, you never know when you’lI become the prey. So you must behave with extreme caution and conform to the hunter in almost all respects. The hunter, however, is not an individual but the System that, using individuals, recreates the ancient horrific game between the beast and its prey. If you want to be free in such a System, you can only distance yourself from it.

But even this position was tolerated by the System only to a certain extent and in particular circumstances. You have to remain at the margins of society, denied the means of survival and certainly denied the possibility of advancing your artistic ideas. In such situations, good and evil become merely prag matic and it becomes impossible to define any judgement or moralizing on the basis of good and evil.

Essentially, the majority became a part of the System, perhaps hoping that step by litile step it would turn the System in a direction less radical then it had pursued in the beginning, hoping al so that a bond would slowly be re-created with tradition and that this bond would not exist in too great an oppositions to state ideology. Many entered the System consciously to protect and develop their profession or the scientific progress of their profession. The policy of small steps was iIIustrated on a practical level in China. The monstrous reaction to the litile steps intended to slowly carry China back to traditional Chinese culture and civilization was dictator Mao’s “cultural revolution”. I think concentration camps are no more humiliating than the physical erasure of a fivethousand-year-old cultural heritage, the daily abuse and even murder of the cultural and scientific elite of the Chinese nation, the killing of sparrows and the other “great leaps” the Chinese had to suffer for “the cultural revolution” promulgated on behalf of the Marxist avant-garde and the revolution. This avant-garde zeal reached its climax in Cambodia where the Marxist minority killed more than a half of its own people because they didn’t have the proper proletarian pedigrees. Such an avant-garde leaves behind horrible devastation and barbarity. Indeed, almost every kind of totalitarianism leaves a wasteland behind it. In Slovenia as well.

I added that “al most” because some totalitarianism systems were able to outdo even themselves. One need only think of Franco’s regime. But the totalitarian systems that were defeated are somehow preferable to those that simply collapsed after exhausting, robbing and annihilating the material and spiritual values of their peoples.

The following is an artistic Gedankenexperiment: consider the possibility that in such historical circumstances, the futurists, for example, longed to trigger an equally fatal avalanche in the arts. But this was prevented by Cezanne and Picasso and by other great twentieth century artists who remained deeply connected with European and global traditions, with traces of the Other. The interdependency of great artists prevents the singularization of art. They knew that to be artistically and spiritually free, one must accept all the world’s art as one’s own, as one’s foundation, one’s basis for reflection. Only then can one give material substance to the artistic vision. To the artistic expression of one’s own vision of the Condition of the world.

The concept of building a new world and a new man was something that all totalitarian systems took literally, deadly, seriously. They were the true avant-garde – or at least they claimed to be. Or perhaps the futurists were only joking. Did they consider their movement to be something optional, something that was not, in the final analysis, so serious? But isn’t art always a deadly serious activity? A deadly serious game? What possibilities did artists have in totalitarian systems as long as these systems were ru led by Nazis or socialist realists? And, finally, we must ask ourselves what possibilities are there for artist in impoverished post-socialist states as compared to the glamour and glory of the “developed world” and its culture industry?

There is a difference between contemporary and so-called avant-garde art: it is based on the continuity of the world, of its heritage and of the presence of the Other. And Otherness. It is based on respect for everyone because they make us what we are.

The purpose of the avant-garde should be to make a distinction between artistic sameness and artistic similarity but this is, I believe, in total opposition to the wishes and goals of all revolutionaries.

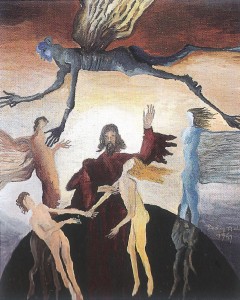

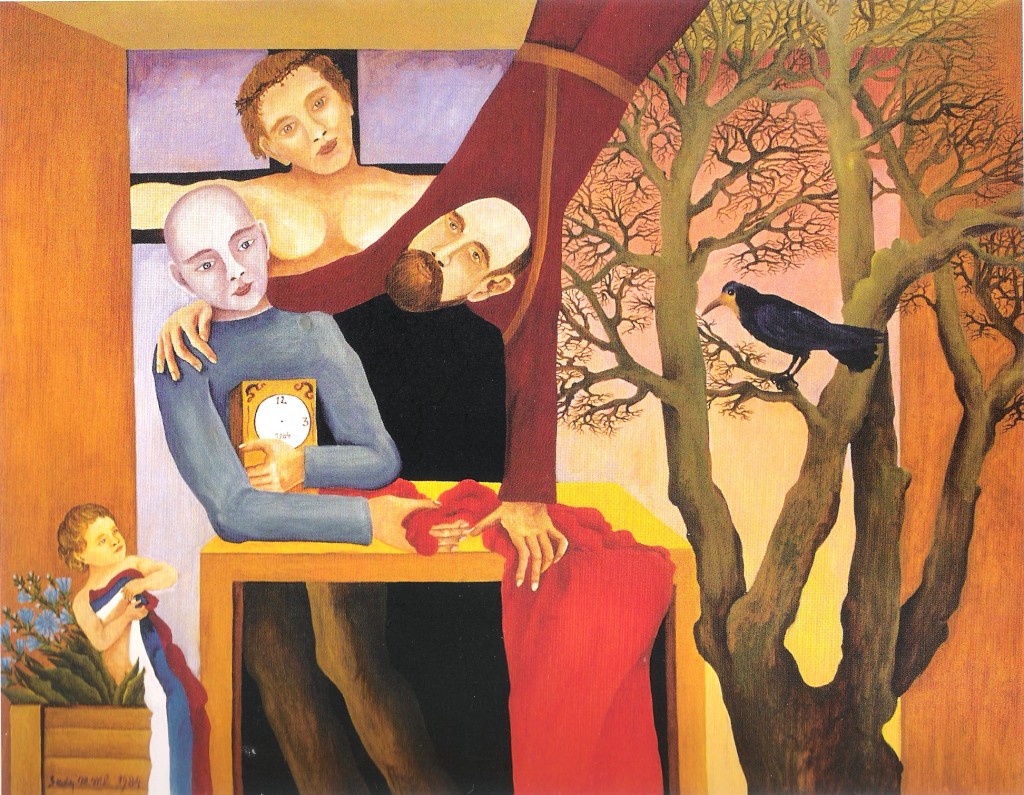

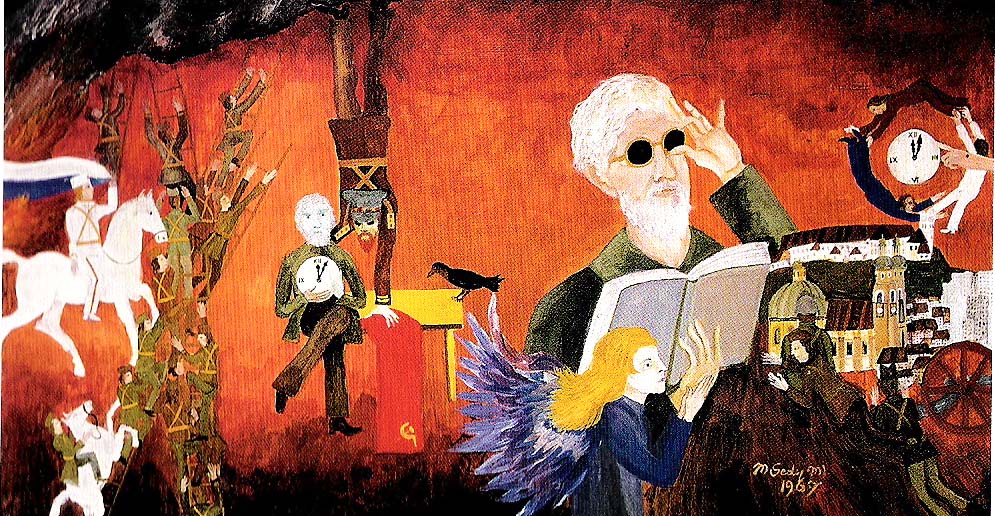

Maksim Sedey yr.: Picture 2, variation on picture Marc Chagalla: Revolution

Tempera, oil on woodpanel, 72 x 135 cm 1967

One of the paintings I created during this period was based on comparisons between Renaissance concepts of good and evil and the times in which I was living. It differed from the paintings that had emerged as an experimental pentaptych painted following the motifs in Hieronymus Bosch’s Creation of Eve.

This other painting, The Garden of Sweetness, appears on the left part of the triptych. Bosch’s vision of the world’s condition was cosmic; it was based on the dualism of the divine, which represents both the good and evil aspects of the secular and human. If you observe mankind from a suitable distance, it is no longer necessary to draw the Tempter or the devil separately. There are in these paintings many hidden symbols that allude to sensuality, inclinations toward evil and much more. Mankind is a blind force and evil rules that force. The Creation of Eve herself was supposed to be the beginning of human evil. In Bosch’s painting, Eve was not created in the heavenly Eden but in the earthly Eden. The tree of knowledge, of good and evil, is lost among other trees; beasts hunt and kill other animals in the animal world of this earthly paradise. The fauna arises from alake, evolves into higher forms and colonizes the landscape – which is the World. What an amazing representation of the theory of evolution for the Middle Ages! On a litile island in the middle of the lake is the source of wisdom.

So the evil is already at home in paradise, in the tree of knowledge. The Great Tempter is the snake that was chosen for a reason as the symbol of revelation or understanding. (A huge fiery snake, a trace of a meteorite or of the cataclysm to co me are deeply embedded in the subconscious of many nations and frequently expressed in their mythologies.) The snake and the dragon symbolize evil in many religions.

The leaves of the fig tree with which Adam and Eve cover their gen italia led many to a totally different symbolism, different from what this gesture should actually mean (our intimacy). When evi I or the devil possessed a woman, devoted sanctimonious believers recognize and destroy it. Yet I have never understood why evil is burnt if hell itself is the scene of the very greatest fire and the devil is the king of fire. In the Europe of those days, they must have burnt half of hell. Perhaps they were consciously enacting hell. Expulsion from paradise meant that Adam was no longer a part of Nature in which all things exist in harmony. Man only freed himself when he was able to distinguish good from evi!. He freed himself from blind forces, from the spontaneity of natural laws and he began to recognize more subtle invisible forces of nature. Both good and evil stem from the dual nature of man: from the man-animal who eats, multiplies and defends his offspring and the borders of his territory just as all living beings do in their struggle for life in nature. Yet at the same time, man discovered eternity, the immortal soul and the godly presence within him – and therefore al so love for nothing and grace -, knowledge which arose from his primary curiosity, his exploratory zeal. Indeed Cain and Abel so fatally marked mankind precisely because of their struggle for affection. Or perhaps Cain and Abel simply represent two ways of life: the first is a life of freedom, wandering with flocks and herds, hunting on boundless territories while the second is the tame life of agriculture and domestication, surrounded with borders and fortified homes and walls.

Fallen angels as emblems of evi I are mentioned in the Bible only in the New Testament: in Revelation (7, 8, 9, 12) and in Luke (10, 12). Evi I and its representatives were defeated and expelled from paradise and se nt to earth. (Bosch depicted them as swarms of insects.) Heaven is cleansed of them but their evil power grows here on earth and perhaps elsewhere in the universe.

The human condition will become ever more complicated with the population explosion. What was once paradise/nature is now threatened by death and extinction. The paradise of an authentic nature on earth is disappearing and dying. Increasingly, it is being substituted by urban civilization where survival for the majority of people is no different than a daily nightmare in the jungle. Today when mankind is able to actually understand the mighty creation of nature by means of technology, it seems sad that most people no longer know what to do with it, what its purpose is.

Bosch’s dualism falls under the strong influence of the old Persian wisdom that prevailed during the Middle Ages. Eduard Meyer formulates the following dilemma as the crucial expression of Zarathustra’s dualism: “The dilemma is inevitable: either God is omnipotent and the sole creator of all things which means that he also created evil , physical as well as moral evil, along with spirituality and all human beings, in which case He is not good but as truth less as nature itself. If the greatest wisdom essentially equals the greatest good then God is not very wise, or, if he is very wise and very good and therefore omni-gracious then he is not omnipotent as these very features would limit his omnipotence. Physical as well as moral evil stems from a diametrically opposed force which has always been horribly adverse to God.”

Carpaccio’s painting directed me not to a definitive victory over evil, because this is impossible, but to the real essence of evil; it directed me to ceaselessly vanquish evil in myself and in my surroundings. The basic construction of the conscience and Identification with the good can be found in the Ten Commandments which are probably much older than Christianity itself. Christianity logically recapitulated these laws and thus committed mankind to them for ever.

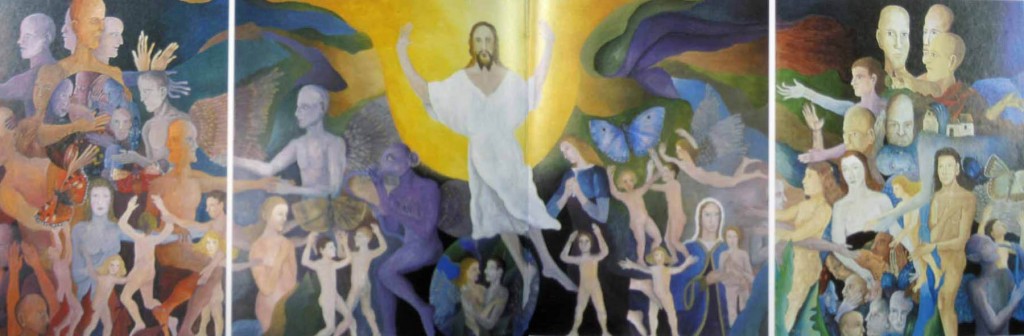

But only Christ and his sacrifice on the cross – sacrifice for universal mankind – revealed the truth and purpose that resides in fighting evil with goodness and love and forgiveness. Fighting it with faith in the Resurrection. Incarnation is only possible in a sphere where evil exists. The question of the source of evil is just as mysterious as the question of the purpose of life, of how to make life meaningful.

Evi I can not be precisely defined at all and evil is by no means merely remnants of opposition to the Ten Commandments. There is no evil in the active love of God. Similarly Christian laws are unnecessary in the active love of one’s fellow man. But unfortunately, only very few individuals are capable of such love.

The refinement of the conscience is only possible with ceaseless growth, with the struggle against e,vil, the defeat of evil. And all of this takes place primarily within the self. Only by building love and the conscience, that is by building the self, can one acquire the power and vision to recognize evil and to resist it.

The growth of mankind and the very destiny of mankind depend on the slightest precedence of good over evil. Good and evil are the two great wisdoms of the universe, the motivating power for everything known to man. Every human is caught in this dilemma, the dilemma of deciding between these two destinies.

Carpaccio’s painting is so magnificent in its artistic harmony and purity that I was much more persuaded by its mysterious beauty than by the literal message I was able to discern at first glance. When I saw the originals of both Carpaccio’s and Bosch’s paintings, I felt their enormous creative energy. It filled me and at the same time pulled me into the paintings, making me accept them in their utmost openness and purity. I have felt this energy in other masterpieces; it is an energy that radiates into the purity of the soul. Into the essence of man.

There are very few people who come into being with goodness, grace and love in their hearts. Christ, at least insofar as he was a man, was the first among them. Such people are our paragons and give us the ho pe and the strength to resist evil even in the darkest times and to try to forgive. Or at least maintain our good intentions by means of grace even when we are unable to love evil people.

I have not finished the cycle Of Good and Evi! though I have already divided it into three possibilities or, rather, three relationships, which I shall explore in this text.

Before I began to systematically deal with these various distinctions, I tried to paint all possible variations and combinations of recognizable symbols of good and evil. (In the case discussed in this chapter, it was Saint George on a horse and the dragon destroying innocence and purity represented in the image of an innocent girl.) Evil is fed by purity and innocence. Variations explored different possible relationships between good and evil , from opposition to equality to an indifferent environment and people who reconciled themselves to whatever was given to them. Evil and good in totalitarian system are almost always grotesque.

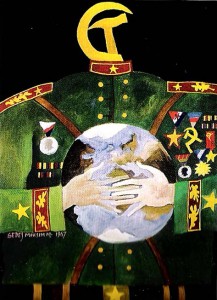

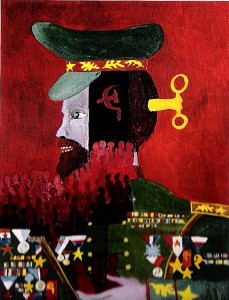

The first possibility l explored was simply to identify evil in the surroundings in which I lived; Slovenia, at the time independent republic of the Yugoslav state that itself belonged to the global empire of communism that controlled one half of the planet, a position which was silently confirmed- though not directly agreed with – by the free capital its world. But actual confirmation or agreement was, in any case, rendered irrelevant since the true symbolic signature was the possession of nuclear weapons.

This cycle of paintings revealed the grotesque interconnection between and identification of military and other repressive powers with ideology. The mass extermination of any possible future opposition, political trials, concentration camps and other horrors were closely linked with the Party’s maintenance of power. *

The first paintings in this series featured “generals” , a response to the military nature of Yugoslav and Slovenian political parties. Later on, I added to this cycle a series of paintings of generals and images of Lenin as symbols of communism whose clock – and time – had stopped. The second part of the cycle represented the blind forces of revolution as a variation on Marc Chagall’s painting The Revolution.

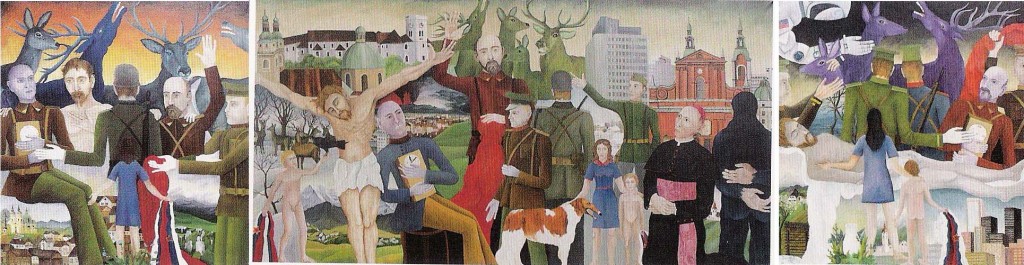

First, I softened the distinctly biased view of the world’s condition by depicting an image of Christ’s hand, pierced and bloody, calming these blind forces. A new viewpoint and approach to the whole imagery of good and evil emerged from this understanding and thus the cycle The Anticipation of National Pacification was born. I treated the relationship of good and evil in this work in terms of right and wrong ways of delivering the Slovenian nation and the consequences of the search for and materialization of ideas.

There is Christ, symbolically present, who in the chaos of prevailing values shows the hope and purpose of suffering; and what seems the most important to me, Christ’s sign shows man how to endure this chaos, to maintain a good conscience and to resist evil , thus remaining human. With the acceptance of Christ, values are finally defined as well as the limit between good and evil.

Hatred and vengefulness are the greatest evils and therefore the temptations which are the hardest to resist.

He last part of the cycle is dedicated to God’s presence in the world. The largest work in this cycle is The Slovenian Way of the Cross. I painted it for a church which has miraculously remained standing for more than seven hundred years though it is situated at the very place where the most horrible fratricide in contemporary Slovenian history occurred. Nobody wanted to listen to or understand the vision of the poet, France Prešeren, who wrote long ago, “Slovenian murdering Slovenian brother. How horribly blind is man.”

The passions of the cross, which symbolically represents the opening of the soul’s eyes, is depicted in the Church of Saint Vid. Blindness of the soul is surely the most horrible form of blindness.

I have not yet finished my cycle on the theme of good and evil. I still do not have the final answer: the synthesis and purpose of humanity and of the cosmic duality.

The pentaptych I painted according to Bosch’s vision led me in another direction. At first I painted several variations and then I discovered that I too was a part of this same humanity, this same nature permeated with evil, the mankind which – according to Bosch – can not be saved.

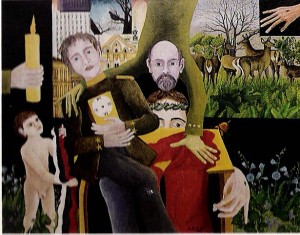

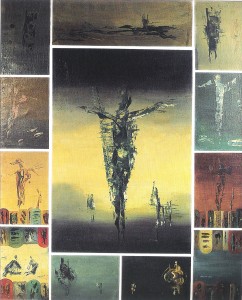

Maksim Sedej yr.: Premonition of National Reconciliation XIX, triptych

Oil on canvas, 135×570 cm, 1985

Maksim Sedej yr: Premonition of National Reconciliation XX

Oil on woodpanel, 160×122 + 160×248 + 160×122 cm, triptih 2000