I. FACE OF THE SOUL – Order and Chaos

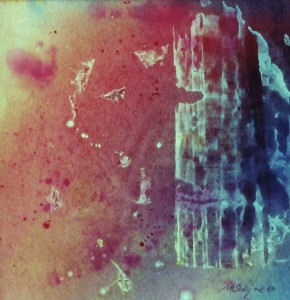

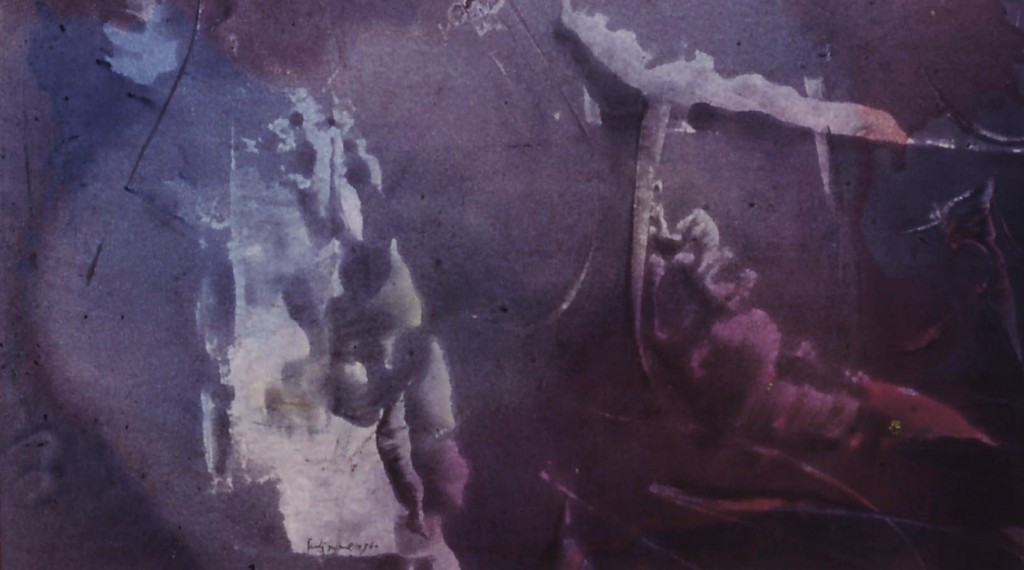

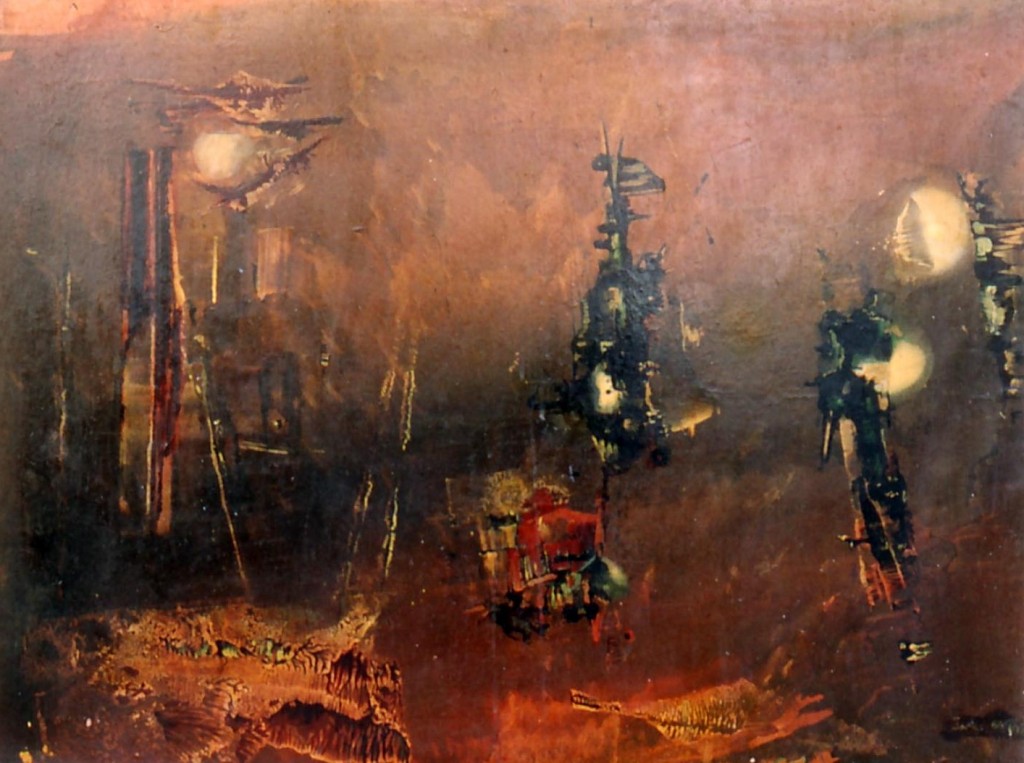

Maksim Sedej ml.: Kompozicija XIII

Anilinska barva na papirju, 59.7×88 cm, 1960

Maksim Sedej yr.: Composition XIII, 1960

The ancient Chinese believed that the soul has four faces or, to put it more precisely, four dimensions. But I will not rest my own description of the understanding of the soul entirely on Chinese wisdom. And I will not pass over the doubts that are felt by all that contemplate death and transcendence, the soul and its immortality. As an artist, I also do not feel compelled to subordinate my viewpoint to those of scholars who believe that the soul cannot be ontologically explained. Or as Heidegger might have put it: I do not feel that it is absolutely necessary to avoid subjective concepts, in particular the concept of the spirit. My understanding of the soul is a poetic one and entails the concept of spirit as the trans-temporal communication of the infinite whole.

I would like to describe certain events from my childhood, which no doubt influenced my knowledge of the world I live in. These notes are meant to be something more than mere autobiography, more than the sentimental memories of a youthful age.

I should also add that the individual events and thoughts laid out here are not linked in a strict temporal sequence. Rather they are built into the text to lend a certain logic to my reflections about truth and painting. Or perhaps they are only the subconscious associations that must rise in one way or another to the conscious mind where they become the building blocks of thought, comprehension and knowledge of the condition of the world and the universe.

It was the first year of the war. It was the time of the police-enforced curfew in the City. Houses had to be darkened. My mother carefully covered all the windows and doors of milky engraved glass with sheets and blankets. A meeting took place in our home at least once a week. These meetings usually lasted until morning when the curfew ended. We watched the events taking place in my father’s studio through a keyhole but could only see what was going on in a mirror of cheval glass that stood right in front of the door.

I mention this because many years later I read U Tai Po’s poem The Porcelain Pavilion and it awoke memories of those times. After an initial period of boring conversation which was not of much interest to us, the atmosphere in my father’s studio became more and more lively – in direct proportion perhaps to the amount of wine consumed. A friend of my father’s, another painter, usually disappeared around that time. Then suddenly a door would open and he would reappear in the room with a great roar of laughter, his naked hairy chest covered with blood. He would stand right in the middle of the speechless company and sing an aria. Then laughing their heads off, the ladies began to lick him because he was not wounded but merely smeared with apricot jam.

One evening the keyhole through which we observed the meeting was veiled in shadow. The door passing into the bedroom from which we were spying suddenly opened and we fell on the floor one on top of the other. A kind man picked us up, seated us on the bed and began to tell us the story of Nature. Of all the wonders of Nature that this kind man, a poet, narrated to us, there was one that remained embedded in my deepest being: the promise that after the war we would all go together into the primeval wilderness of Nature and become a part of it. Utterly naked, we would hunt like wild animals, warm ourselves around a bonfire and talk of our heroic adventures.

I never saw the poet again. Some time later my father brought home a newspaper which featured his photograph. He was bound with barbed wire and surrounded by armed men. The poet was later shot and I have not forgotten him to this very day. Even now there are some evenings when before I fall asleep, he sits on the edge of my bed and tells me once again the story of Nature. The extraordinary thing about it is that the story grows more and more magnificent and perfect with the passage of time.

A long time ago God, silently and almost imperceptibly, entered the story.

After my encounter with the poet, a certain restlessness and longing for the wilderness andprimeval nature haunted me. The City was occupied by a foreign army and enclosed with a barbed wire fence. You could only got out with a special permit. I knew this because I was once chased away when I tried to leave. I explained the whole thing to my father and is response was exactly what I expected. Father kindly thanked me for my trust and then explained his own opinions to me. He told me that the City is the scenery of the world and not the nature that the poet had revealed to me. Nature is a spiritual outing, not a physical wandering across the fields. Then he seemed to reflect for a while and finally concluded that nevertheless I was absolutely right, that he entirely agreed with me because he also understood the “call of nature” (which had supposedly called to me). But he made me promise him two things: first, that I would wait until the end of the occupation and, second, that I wouldn’t breathe a word of this to my mother. And there I was right at the beginning again. I still couldn’t shake the restlessness and longing for nature awoken both by my encounter with the poet and by the strong spring thaw. I went to my friend Miro. He was a shoemaker and he could solve any problem I came up with. If somebody expressed doubt in his abilities, he pointed to a big boot hanging from the ceiling of his workshop and said, “If it isn’t true let the boot fall on my head.” It never did.

Miro quietly listened to my “problem” about passing the checkpoint and leaving the City. “We’ll settle this at once,” he said. He tore a sheet of paper from the lined notepad in which he wrote his orders and receipts, then concentrated a little, licked his pencil and very slowly wrote something down. “Now you will have no more trouble at the checkpoint,” he said. “Just show this paper and take a jug for milk and don’t forget the money. If they ask you anything tell them that your father wrote this.” After leaving Miro, I looked incredulously at the paper but I couldn’t understand anything because he had written the message in the strange letters of a foreign language.

The melting snow along with a strong rain prevented me from setting out on the expedition the very next day. The river flowing through the City in its concrete waterbed was filled almost to the halfway mark. It rushed along its way, troubled and muddy with the special smell of snowy broth. The land around the City, at least the part I wanted to explore – the marshlands known as Barje were flooded. I set out as soon as the waters subsided and Barje dried out a little. It was a warm day. Mother gave me money and a milkjug. She was happy that I was willing to wait in the endless queue of people who waited for milk every day. But she also knew that I didn’t like milk very much and was probably up to something. It was easy at the checkpoint. A soldier took my note and returned with an interpreter who asked me what my father’s profession was. I answered that he was a painter. The interpreter returned to the army building. After a while an officer of the foreign army came out, winked at me, waved his arms like a bird indicating that I could go. He wrote something on my slip of paper and gave it to the guard who then handed it back to me.

When I finally got to the other side of the wire surrounding the City everything inside of me began to sing. I wanted to cry out with pure joy. Something inside of me burst open and my blood seemed to flow in waves. I stood in front of the endless plain beyond which the mountains rose and it looked like one great untouched Nature. Only two lone farms squatted in the field not far from the check-point. In the first, the farmer poured milk to the edge of the jug and then put a big dollop of cream on top. When I gave them the money, they added on a large piece of bread. Everything was going swimmingly – it could hardly have gone better. After that, I rushed towards the woods. The road forked immediately after the first farm; the wider path, strewn with gravel, led to other Barje villages, and the narrow one, a cart path, wound over the vast landscape right into the distant mountains. Or at least so it seemed to me as I walked along it: the line drawn by the cart path vanishing into the horizon. At the beginning of the path, individual trees grew on the side and then slowly the path became narrower and narrower until it was nearly overgrown by grass and bordering bushes and blackberries. Soon a wide ditch filled with black marsh water appeared to the right of the path. When after a few hundred more meters I paused to take a deep breath and enjoy nature, I couldn’t help feeling a little anxious. Except for the sound of crows croaking at a distant rubbish dump, I heard nothing at all. The birds weren’t singing. The putrid marsh water stank. This smell mixed with a second smell that was even less pleasant. It seemed to came from behind a thick bush and a tall solitary fruit tree overgrown with ivy. When I parted the branches of the bush, I shuddered with fear: a huge animal, perhaps an ox, was lying in a little hollow under the ruined, blackened remnants of a house. Its belly had been blown out. A thick cloud of flies hovered over another such animal and an overturned farmer’s cart. When I studied the scene, wanting to understand what I actually saw, I noticed two wicked little eyes watching me from behind the overturned cart. In the end I didn’t understand what had happened there and I fled panic-stricken back to the checkpoint.

I couldn’t begin to imagine the danger that might be following me so I kept looking back over my shoulder as I ran. Only when I was right in front of the check-point did I hear the loud cheering and exclamations of the soldiers. They roared with laughter when I fell and spilt the milk. Funny or not, this episode provided me with a free exit from the City. Each time I appeared at the checkpoint, the soldiers laughed and let me out without any questions.

The path ended at a tributary of the Reka river. In the middle of the stream, a remnant of a bridge jutted out of the water. Uprooted trees and giant branches carried along by the water were caught around the ruins. I could go no further. Some kilometers higher up the stream, a wide watery ditch filled with reeds flowed into the tributary. The water in the ditch looked shallow yet when I poked a stick into it, I couldn’t feel the bottom. No matter how long a stick I used, there seemed to be no bottom under the mud. The tributary here was like a muddy trap. When I had been poking about for a long time, the farmer in the nearby house gestured to me with great anxiety. He told me that at that hour of the day, large detachments of foreign soldiers usually come to the tributary and woe to me if they found me there in the bushes. He wasn’t interested in what I was doing there – setting fish hooks in the water or linden branches for birds in the bushes or snares for rabbits and pheasants – and it is true that I had already found quite a few of these devices during my explorations. He advised me to spend as little time there as possible. “Many a milk purchaser has been caught by quite a different trap in these parts. Mines were laid in the bushes around the burnt-out house the day before yesterday. And nobody knows what they will do next. Every day they come up with something new, something more wicked.” I should stay away from the ditch – he pointed to my tracks at its edge. “It is deadly dangerous.” He frightened me so much that I didn’t go there again until after the end of the war. And only once after the war – right after it ended. I wanted to visit the farmer but he was gone. The house was abandoned and falling to pieces. I asked at a few neighboring houses but nobody seemed to know anything about the farmer. They only looked at me strangely and that was the end of it.

Some years after the war, a lady in black stopped me and asked me if I was the young gentleman who used to go to her grandfather for milk. When I nodded she told me that he was gone and would never return. He and her grandmother had been taken away and nobody knew where. She only knew that they would never come back and even that was a secret. A few times when he had gone on errands to the City, he had wanted to pay me a visit but had felt embarrassed. He was very shy and loved nature dearly. Her brother had drowned in that ditch when he was my age. She quietly wept and I had to promise her that I would never speak of this with anybody. I did manage to indirectly tell my father about these events. Only the ones that seemed the most urgent to me. But he was extremely cautious, even more than he had been during the war. He wanted to see that slip of paper. Although I had already decoded it myself, I showed it to him and he never gave it back. He said he mislaid it. The words, written in the German Gothic alphabet, had said: “Respected commander, the young black bird likes to drink milk. So that he doesn’t fall out of the nest and dry up, let him go to some good people for a draught of fresh milk. His father.” Below that there were additional words in another sort of handwriting: “Let the young black bird go, Commander.” Father didn’t ask me who had written this and I didn’t tell him. He knew all too well that I wouldn’t tell him anything if I didn’t want to. When I told Miro the story about the farmer, he looked at me in silence for some time and then said that it was even more dangerous now than during the war. But because I had been quiet about the boot on his ceiling, he would trust me again. »They are in the woods you explore,« he told me. »Deep underground. And they are not dwarfs.«

A short time before that incident, Dusan Pirjevec visited my father. He kissed my mother and called my father “Makselj”. He brought a big bottle of wine. I was in the adjacent room, quietly doing my homework and they didn’t realize I was listening. It was then that I heard what happened in the woods after the war. It was then that I understood that they weren’t dwarfs. This knowledge somehow assuaged my guilty conscience for shooting my gym teacher with a slingshot from behind some bushes and knocking out two of his teeth. I did it because he had slapped my face when I didn’t practice hard enough for Tito’s relay race at the city stadium. The teacher suspected that his assailant was the husband of the music teacher whom he was secretly dating. But nonetheless he forbid me from appearing at the stadium. And I never appeared any other time. Something always prevented me.

I could easily reach the mountains at the edge of Barje. The railway station was packed with people and so were the trains. If by chance a railway guard asked – though it never happened I would have told him that my father was holding my ticket in the next carriage. I usually got off the train just below the hills at the third station from the city. I walked for a distance along the rails and then turned straight up into the woods.

First there was a steep grass slope in a small valley where one humble house stood. An overgrown path led from the house straight into the wood. Firewood and timber were transported along this path down to the valley. I explored these woods over a period of several years. I discovered a small hollow under a stony overhang high up in the hills. The hollow was surrounded on three sides by old trees. The stone overhang was free of foliage – only a few bushes grew at the top. A big airy hole opened above the hollow and you could see the sky through it, especially at night. The air was very clear up there and usually so sharp that stars appeared only as little clear spots of light. The Milky Way extended above the whole opening and cast a mysterious light in the sky. There was also a hole in the ground at the bottom of the stone wall. It was approximately one square meter wide and appeared to be the entrance to an underground cave where a she-bear bore her young every couple of years. There was a great ravine in the forest to the north of the hollow. I discovered it once by accident, the year it rained incessantly for ten days. The Reka and her tributaries flooded their banks. Almost all of Barje was flooded. When the sky finally cleared, I went up to the hollow. The wind blew stronger and stronger and when I reached the hollow, I heard something that sounded like a horrible explosion. A giant branch broke from an oak tree and fell vertically down into a heap of dry branches and twigs. Then the whole pile just seemed to disappear. Naturally I immediately went to explore what happened to it. A round hole, more than a meter and a half wide, gaped open in the place where before there had been the heap of dry brushwood. I could see around the edges of the hole the remains of a cement vault at least half a meter thick that must have once covered the hole. When I threw a stone down into the abyss, it ricocheted off the walls. It was obvious that the cavern curved round and was covered with rotten brushwood and branches at the bottom. I never heard the stone hit the bottom.

The brushwood was not the only thing at the bottom of the hole. I learned that not long after having discovered it. When I asked about it at a nearby farm, the landlady crossed herself and the men dispersed. They simply vanished. But the secret didn’t remain secret for long. When I returned to the valley one autumn evening not long afterwards, an old man from the farm was waiting for me in the forest. He sat on the fallen trunk of a tree with a bottle of brandy beside him. The bottle was carefully corked and the cork was covered with wax. I sat down beside him. The darkness hung very thick before he broke the silence. “I am ninety-three years old but I still thought it better to wait for the hunter to leave. You must have seen him yourself since you are at home in these woods and you have also been silent for more than an hour.” It was true; I had seen the hunter twice that day. In the morning when I arrived, I had seen the back of his coarse green woolen coat and the tuft of chamois on his hat. And when I came back, I had seen him for the second time. Even in the instant I had spotted the old man sitting on the tree trunk, I had noticed the front part of the hunter’s knee-high boots tied with white laces. This was alii could see of him from behind the mighty oak. The boots disappeared a second later. That’s why I also sat silently on the trunk and waited for the hunter to go. Then the old man told me that his son had seen a bouquet of dried thistles on the brushwood with which the big hole was newly covered. The thistles had been a special blue color. Indeed there were always flowers at the top of the hole. “I put them there myself when I am on my way home from the woods. I won’t ask why until someone begins to speak the truth about it. I’m about to depart this world so I know what respect for the dead means. My own brother and many other relatives lie in that abyss. But you must have already figured that out for yourself. Here is a bottle of brandy from before the war for your father who must be a very respectable man.” Then we slowly descended through the thick darkness to the farm. The old man died shortly thereafter and with him all his knowledge of the woods that he hadn’t passed on to me. As far as the flowers were concerned, I got some from my mother and laid them on the heap of branches to dry. The hunter warned me that I shouldn’t do that. So I kept on doing it just because of his warning. Or maybe there was another deeper reason for my actions of which I was not yet aware.

The longer I kept on going to that little valley in the hills, the more conscious I became of the fact that the City and the nature around it are one and the same thing, while the sky – meaning the stars and the galaxy – are something completely different. Nature’s call to me no longer came from the forest where hunters, foresters, lumberjacks and gatherers of mushrooms poked about. It came instead from that little piece of the sky above the clearing in which I watched eternity. It came from the opaque night between the trees that I studied while listening to the mysterious nocturnal noises that transformed the forest into something ancient and primeval. Into the Ancient Home. Years later I read Ted Hughes’ poem Crow’s Theology. This poem provides the most accurate reflection of my thoughts during that time

CROW’S THEOLOGY

Crow realized God loved him

Otherwise, he would have dropped dead. So that was proved.

Crow reclined, marveling, on his heart-beat.

And he realized that God spoke Crow Just existing was His revelation.

But what

Loved the stones and spoke stone? They seemed to exist too.

And what spoke that strange silence After his clamor of caws faded?

And what loved the shot-pellets

That dribbled from those strung-up mummifying crows? What spoke the silence of lead?

Crow realized there were two Gods

One of them much bigger than the other Loving his enemies

And having all the weapons.

I hadn’t yet considered in those days the possibly of painting a picture of my longing, of the trace of nature’s call. When I looked beyond the fleeting nature of things and toward the infinity of the Universe, I became confused. It was the same sort of confusion I felt kneeling before the face of God in the cold marble of a church, asking him to give me some sort of sign. He didn’t give me one and I didn’t give up. In one way or another I tried to obtain through prayer and entreaty a sign of His existence. At home, my family was wisely silent about the face of God; they knew there was too much evil in the world. Both father and Miro, the shoemaker, had said so. But Miro, as always, had something brewing at the back of his mind. Father was regularly visited by the catechist, Lavric, and they talked about things in a language incomprehensible to me, a language full of symbols and associations. They didn’t speak of God. When I asked the catechist about God he seemed puzzled; he surreptitiously glanced at my father and said to me: “You have learned that in Sunday school and you know God and his Creation very well. I also see that you come to Mass frequently but you cannot rationally comprehend faith. Genuine faith, I mean, not the one which now stands in for the pagan idolatry of secular ideas in our state.” Then my father stopped any further discussion in this direction. When the catechist left he suggested that I look for the answers in books. Father always avoided such discussions but he said that from that moment on I would be free to contemplate all the books of the civilization that had been so brutally pushed on to the “rubbish dump of the history” where it still lies now, stained and bloodied and denied by its own revolutionaries. James Jeans’ 1938 book The Secrets of the Universe, which had an important place in my father’s library, kindled my interest and opened my mind to the scientific horizons of the universe and its vastness. Yet somehow, despite the magnificent images of universal vastness revealed by its scientific author, I didn’t fully experience the mystery and the mysticism in this book. It would be Dostoevsky who would open the door, albeit only slightly at first, to the spiritual infinity of the mystics. Even today, Father Zossima and the Grand Inquisitor are for me the incarnations of the great truth of this world.

Before the war my father invested all his money in books. Even during the war, when we had practically nothing, he weighed each and every coin in his mind before deciding how he would spend it. My mother used to weep on the many occasions when he brought home a pile of books from the secondhand bookshop. But I never suffered from lack or hardship though it is certainly true that sometimes we really had nothing, not even socks with holes in them.

- Maksim Sedej yr.: Composition 1960/16

Anilin colour on paper, 47,5 x 48,5 cm

I was very much occupied with reading books. First, in accordance with my father’s selection, and later, when I started going to the woods, in accordance with my own interest. I could think about books by myself. Poems were the most mysterious to me. I could stare at the starry vastness in the few lines of Preseren’s Creed for hours and hours. When I read this poem today, I still experience those wonderful moments in the mysterious wood, my nocturnal viewing of the mighty galaxy and the stars beyond which eternity was unfolding.

PRESEREN’S CREED

What is must flee.

But is flight not God,

ever leading to heaven above, what is, what was and what will be?

I learned about chaos as a cosmic dimension when I read Abbe Lemaitre’s theory of the Big Bang. What first caught my attention was the fact that matter, which originates in nothing, has a finite amount of substance. Another illuminating discovery was the theory of the “Cosmic Egg” which burst open in a magnificent explosion and so created the universe. And my third amazing discovery was that the “Cosmic Egg” was infinitely large regardless of the fact that scientists estimated its size to be similar to that of a solar system. The existence of this universal seed overwhelmed me to the point that I had to immediately make a drawing of it. In fact, although contemporary theoreticians have shrunk it down to the size of an atom (which can also be infinitely large) and nowadays even to the size of incomprehensibly tiny “strings”, the cosmic seed still forms the basis of many of my paintings The universe is expanding and original chaos right along with it. But it was clear to me even back then that chaos expanding in an isotropic universe must be subordinate to certain laws, that even at the very beginning it had been subordinate to the laws of an expanding universe, and that this chaos is the chaos of the scholar. On the other hand, the chaos of human thought about the meaning of life and man’s attitude towards creation is the chaos of the thinker. In those early days this distinction was much more intuitive, much more clear and authentic to me that it would be later when I began to bring order to my thoughts and discoveries, an order which I had discovered in the work of seekers similar to myself. It didn’t matter whether the seeker was a poet, a scientist, a philosopher or anyone who had come to the conclusion that mere survival or submergence into the vanishing polluted earthy primeval nature or even into the chaos of the metropolis doesn’t provide a satisfaction equal to the wonder of life, a wonder that mysteriously has been granted to us all. *

There is a difference between the chaos of the scholar and the chaos of the thinker. This difference is based on the relationship between the order and chaos of the universe on one hand and the freedom and unpredictability of human thoughts and deeds on the other. If we only take a glance at the vast enormity of the universe, we immediately see that everything is subordinated to certain universal laws (Inclination), even if we don’t know or understand them yet. Perhaps order isn’t really the right word and that it isn’t even obvious what this order is supposed to be. One thing is certain: whatever it is, it is not creating the universe according to plans that have been precisely determined in advance.

Moreover, this order is not something that should give us false hopes about the meaning and purpose of all that is human and cosmic: it is not some sort of universal Order. I would prefer the term: Inclination – an inclination towards something more organized, more complete, as well as an inclination toward things which are not yet comprehensible to man. Let us say towards a spiritual universe, towards love and God. Once the brain evolved in the first mammals, it was destined that these wonderful creatures – our distant ancestors – would develop regardless of the decline or evolution of the dinosaurs. Just as mammals settled in oceans where total killing machines ruled (and still rule), so too did dinosaurs rule the land eons ago. Anthropologists are well aware of the great number of humanoid beings that evolved in nature before Homo sapiens. When at a certain point there were sufficient possibilities and variations, nature made the quantum leap that essentially brought nature’s experimentation to an end. Man took matters into his own hands.

As far as the stars and the galaxies are concerned, it is not possible for us to say what chaos means. Huge gas clouds in branches of the Galaxy may belong to chaos but they also may belong to order, or to an inclination towards forming stars in accordance with certain physical laws. The size and physical characteristics of such gas clouds before they become stars are determined by a number of specific factors and cosmic forces. After the process of star formation, the remaining gases disperse and sooner or later they gather again into new clouds which eventually will comprise enough substance to create new stars. Such substance comes from supernovas which scatter a variety of different elements into the universe: the primeval substance and energy united in atom particles, atoms, diffuse gases, nuclear reactions inside stars etc. And thus galaxies and huge galactic islands began to flow into the universe on the basis of nuclear synthesis. The initial explosion, the forces of gravity and other galactic forces, the beginning of energy or matter in the universal vastness, are all supposed to cause the expansion (or curving) of the Universe. If we understand this curving correctly we understand that Heisenberg’s determinant of unpredictability is an important component in this Inclination. Sooner or later Nature sweeps up all accidents, examples and unsuccessful trials into history.

Chaos and order in the macrocosm are easier to imagine, at least for me, when seen in the context of this symmetry and Inclination (shall we say towards a mysterious order). And this relationships between chaos and order gives the artist unlimited imagination.

Where classical science ends chaos begins as the unordered part of nature, its unresolved and erroneous aspect. Chaos and order coexist in nature. Yet it may be that when considered in the universal dimension, chaos also functions as order. Chaos has its role and its limits in the structure and reality of the universe, so we must not make hypothetical generalizations or illustrate it with patterns that are “endless” or that could be repeated “infinitely”. Every theory or thought of this kind leads into a singularity that, in any case, is not possible because of the codependence, which reigns in the universe. Universal order or codependence and the equilibrium of matter prevents chaos from expanding into infinity and replacing it with Nothingness. Many dilemmas for the scholar begin with chaos. But a thinker comprehends chaos in a completely different way because he is not bound by the finality, infinity or the curving of the Universe; nor is he inhibited by the micro- or macrocosm. Chaos for the thinker is human chaos. A thinker who understands chaos on the level of man possesses a criterion that the scientist does not. Chaos for the thinker essentially represents the question of the meaning of life, a question the thinker asks or contemplates only within the framework of abstract thought. It is a principle he invents himself and one, which allows him to ask crucial questions and eventually to answer them.

Chaos for the scholar is much more abstract than that of a thinker. James Gleick says that the order inside chaos is the oldest cliche in science. The idea of hidden unity and a common uniform model in nature is attractive in and of itself but unfortunately it has always inspired poor scientists and odd persons. It would be interesting to compare such thinking to the opus of Vasilii Kandinsky who at the beginning of his abstract career painted a wonderful world of colors. Using combinations and harmony, he created new color harmonies in a way never seen before. Yet towards the end of his life he abandoned this orgy of colors and spontaneity and painted a sort of abstract order from sharp pointed abstract forms – from objects. As if the cognition of a mystic who expressed and followed the truth had been replaced by the work of an artist who, as far as truth is concerned, was placing a bet on the sign of Judas (according to Saint Paul, one of the four aspects of truth).

I believe: Despite the enthusiasm of Heisenberg and Glieck to put forward the scientific truth of the universe neither, on this Procrustian bed, was able to understand Albert Einstein who believed in both order and God because he thought trans-cosmically (as did Planck and nowadays Hawking). These scholars were aware of the spiritual dimension of the universe. They knew that the universe is not only a matter of mind and matter but also a sphere of spirituality where the two are inseparably linked to Creation. They knew that rationalism alone is not sufficient to understand the universe. We could say that such scholars carry within them not only a gift for objective scientific reality but also a trace of the poet.

James Glieck’s opinions have already been condemned by Benoit Mandelbrot who revealed order within chaos in a different way. But before we opt for one or the other of these possible interpretations, we must also reflect upon the measures and limits that define chaos.

In its beginning, in the first billion parts of its existence, the universe was like a very hot “soup” teeming with all kinds of arch-particles of matter and anti-matter along with an infinite amount of energy. What remains of this scientific soup – what James Jeans calls arch-chaos – is our Universe today. The first sound of the Big Bang confirms this finding. When Benoit Mandelbrot speaks of the English coast, he poses an insurmountable problem before James Glieck. The length of a coast cannot be measured (or even perceived) without some sort of measuring tool. That means that nobody will be able to recognize the English coast if, for instance, we were to magnify its atomic or sub-atomic particles or if we were observe it with a modern telescope from the possible planet of some nearby star. A planet that was discovered only recently. We speak of relativity where the position of the observer affects measurement and this specifically relates to what science can discover regardless of the measuring tools used by man, indeed regardless of his existence and his comprehension of the universe. Heisenberg thinks that these measures are both objective and subjective, that they depend on historical conditions in the objective world.

If I, as an artist, simplify the problem I can merely say that science is unable to distinguish its understanding and explanation of the universe from man. That is, from itself. This is the transcosmic dimension and contemporary science has yet to even come close to it, is incapable of understanding it in its entirety. Because of such viewpoints, Einstein, even though he opened the way for a different explanation and understanding of the universe, was considered conservative by some of his renowned contemporaries.

Man sees in precisely determined intervals of light waves. And in a similar way, his cognition of Creation taking places in (human) cognitive intervals.

I ask myself: Is chaos something that exists outside human measurements and is it connected to the anti-symmetry between the micro- and macrocosm? In practice this whole line of questioning represents a new science, a freshly acknowledged sort of natural phenomena which is present everywhere. James Crutchfield thinks it represents dynamics with positive but finite physical entropy. Chaos has opened hitherto undreamed-of possibilities in science.

In this context, it becomes impossible to arbitrarily explain the theory of the scholar’s chaos. My purpose was only incidentally to point out the difference between the chaos of the poet and that of the scholar. And what is order? Is universal order also a matter of subjective and objective recognition? Historical circumstances? And is it – as opposed to chaos – the symmetry between the micro- and macrocosm? Einstein and Planck saw with their spirits beyond the duality of the universe; they saw order in God and not in the succession of coincidental events which consciously or blindly direct (or fail to direct) the expanding universe. Therefore, their research and their comprehension of the universe is, at least for me, an active prayer to God.

In the depths of the Universe, the scientist will sooner or later find the remains of the primeval “soup”. The beginning of the explosion. He already hears the sound of the bang. He sees a similar “soup” in the macrocosm. Up to ninety percent of the matter that is missing is presumed to exist on this level.

The artist or the thinker is not only searching in the depths of the universe – and in their own depths (in mankind) – for their cosmic primeval origin. They also seek there the whole universe such as it is at this moment in time. Not only the physical but also the spiritual universe, the latter being something strange and marginal for the scientist. Something metaphysical. Perhaps something like love or God. The greatness of love cannot be measured or proven scientifically. Not even with fractals or quanta. Love is not a journey or a glance into the past. Love is a trace, a presence of the (Total) Other in the eternal present. The poet doesn’t need to study the universe in the past to feel or understand it. A poet feels and recognizes the universe as it is, in its deepest mysteriousness and greatness, in the interval between the past, the present and the future, in the infinite whole.

The greatness of man and his cognitive possibility – revelation – lies in the very endeavor to discover the truth among the countless convictions of scholars, thinkers, theologians, poets and others who perceive more than just themselves. But no man is able or allowed to possess the truth. The truth is the substance of all people in general and of each individual in particular. Even of those who reside within the limits of a blind, deaf and dumb truth. The truth is an enormous responsibility.

Mind is only a fragment of man’s essence, a small fragment that can never rationally understand the sacrifice. The sacrifice of one’s own life for happiness, for the life and salvation of another. Such a sacrifice can be comprehended only by the soul. Jesus Christ gave us this revelation. He showed us the truth. Maybe it is the poet who addresses Creation on our behalf. Who addresses God.

I have never tried to apply the notion of chaos to abstract art in such a way that it would be the source (origin) of this art. However in my search to understand the essence of abstract art, I immediately noticed that it shares many parallels with chaos between Heisenberg’s rule of indeterminacy (which is a law) and a finite abstract image on canvas or an image created by a computer program. Science and technology and their consequences are, despite their abstract foundation, very concrete things.

The indeterminacy of individual subatomic particles is not merely an abstract idea but is in fact a part of the microcosm. If we reduce a living human body to its subatomic particles, it will be very similar to the cosmic “primeval soup” that appeared following the obliteration of matter and antimatter. Particularly if it occurs at a suitable temperature. According to Niels Bohr, there are sufficient reasons to assume that a test based on the laws of quantum mechanics, would confirm the validity of these laws in a living organism as well as in dead matter. Abstract painting is based on the beauty of color and brush strokes, iridescence or computer variability and, in a precisely determined world of image and anticipation, presents a vision of tragedy, love and the apocalypse. Nowadays, however, an abstract painter doesn’t need to know or understand anything; mere trade skills will suffice. And these are determined by the specific circumstances and mentality that influenced this kind of painting since its beginnings. At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, several events thoroughly shook the world: the theory of relativity, Husserl’s phenomenology, Zarathustra’s tradition, anthropological and other scientific findings; not to mention the theory of light and the development of methods that preserved light and images on photographs and film. As a result, the well-regulated cosmic order collapsed: not only on the planet but in the universe as well. The period was also marked by world wars, revolutions, emancipation of enslaved nations and peoples as well as the emergence of unique individual personalities. Abstract painting was a radical break from everything that had preceded it in the visual arts. If Marx had been a more poetic and aesthetic soul, he would no doubt have been the inventor of abstract art. In some ways, he is its godfather.

Malevich understood this aspect of abstract painting. And for this reason he attempted to find the harmony and symmetry of the universe in crystalloid or geometrical synthesis just as Kepler created his mystery play of space many centuries before. *

Yet Malevich’s encounter with the actual world was horrible and that is how he painted it. In his paintings, the world and the country in which he lived are populated with people who have no eyes to see, no mouths to speak, no noses to even smell, no ears to hear sounds and words. These formless people, these people lacking even personalities, these non-persons, were a commonplace in Soviet life; they were killed or lost in communist camps and gulags and thus they passed into eternity. But into what eternity? What was such an eternity like? In today’s postmodern world, abstract painting is actually an escape into personal dreams and traumas. It is a deliberate and conscious alienation from the secular world and from the past – which in no way lessens the aesthetics and beauty of this sort of painting. It has been used and exploited more slowly than other aesthetically and philosophically-based styles not to mention individual poetics which tend to be more quickly exhausted through imitation, repetition and changing times. When various social systems became aware of this, they adopted and accepted abstract art and used it as a token of freedom in an otherwise totally alienated and enslaved environment. An individual who has power and sees the truth will express it in his own poetic way, whether abstract or not. The majority of artists, however, work at this in vain because they believe that abstract painting places man before a new beginning, that it represents a new birth unburdened by the past. This is what Marx thought. Whenever I try to evaluate the findings and beliefs of scholars, thinkers, artists and other individuals, I have always favored those with a special talent for comprehending the universe and mankind in their entirety, those who haven’t lost themselves in the infinite enormity of the universe and mankind.

This conclusion about artistic reflection, about the poetic and scientific achievements of mankind, provides the necessary framework for my entrance into visual arts.

My father and the writer, Vladimir Bartol, once had a rather turbulent discussion about Zarathustra. At that time, Nietzsche was still officially believed to be the philosopher of ideological evil and it was very dangerous to openly discuss him. Despite the dark wine they were drinking, their debate was interwoven with temporal and spatial associations in which we actually seemed to be members of an underground movement. For us the post-war years were like a decade-long excerpt from George Orwell’s 1984. They both concluded at the end of the discussion that they could never become a socialist type of “new man” and that, in such a system, the existence of something “beyond good and evil” was impossible. Although I had participated in the discussion, the two seemed to be bewildered and surprised when they actually looked up and took notice of me. The word “eternity” which I had mentioned along with the universe seemed to frighten them rather than to elate them. The vision of the eternity we were living was quite similar to Malevich’s last paintings. Everything in our lives was silently overwhelmed by the agitation of the dictator who, for all creatures like us, exclaimed, “Long live death!”

Although I knew that my father secretly observed my artistic output, neither of us ever spoke about it. But following that discussion my father said to me: “Paint or draw what you think and what you have known and seen in nature, in the woods and along the river and what is Above which is so unconceivable and mysterious. But you mustn’t forget where you live, how and why you live in the City.” Then he gave me a large sheet of paper that he had kept since before the war. I knew that this was a great sacrifice on his part since paper was not available after the war any more. Bartol took note of it too; he wished me every success and he promised that he would follow my work. *

Individual segments of the scene I drew on the paper had been appearing before my inner eye for a very long time. They consisted of a transparence in which the sky combined with the thickening blackness of the evening forest, with unrecognizable figures from the foreign and local armies which ruled the City, and expressed the hope that secularity wasn’t all there was. I was seriously asking myself at that time about the roots of man – where we came from and what we were. I was asking if God and eternity weren’t merely a dream in which we plunged ourselves to escape if only for a brief instant the cruelty of our reality. Our commitment to death. The fleeting wonder named life. That’s why I begged God for a sign or a trace of his existence.

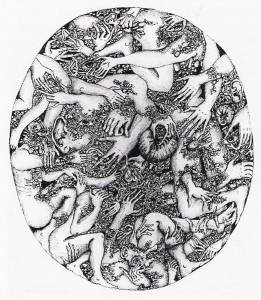

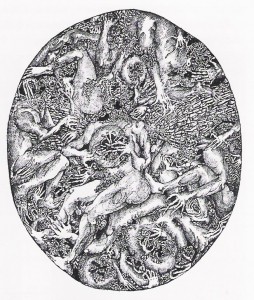

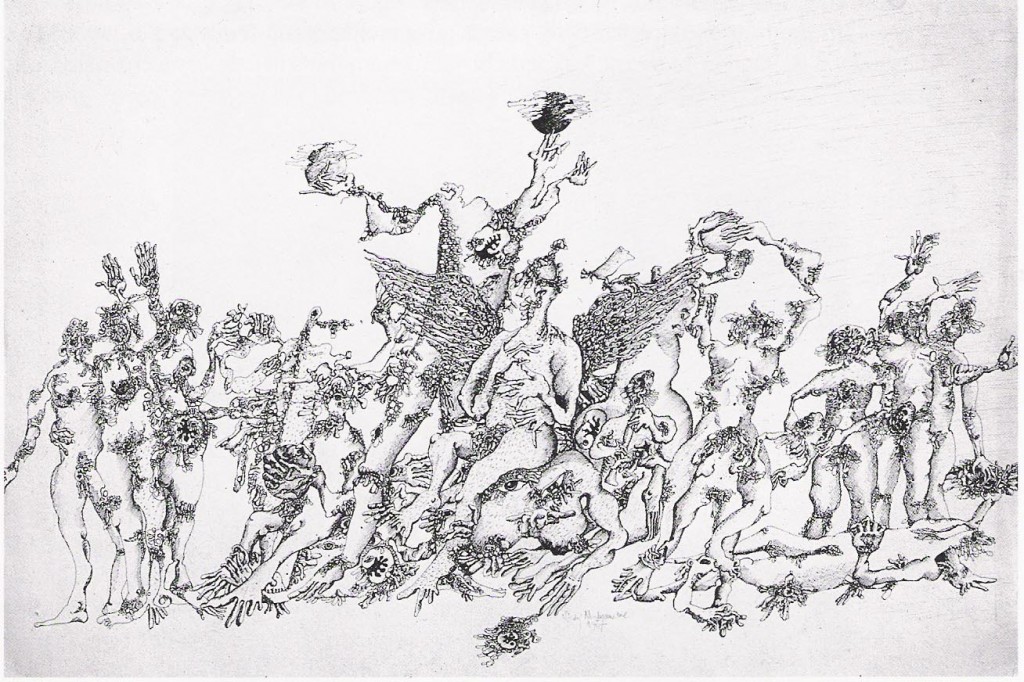

The drawing was surrealist. I drew in the middle an image like an angel with outspread wings. The figures around the angel had unusual shapes and were composed in such a way that the whole drawing gave an impression of balance. The scene to me seemed like something that existed beyond order and disorder, beyond good and evil. It was not – despite its appearance, which may have suggested otherwise – an apocalyptic vision of the end of all that existed. I felt the drawing was the first step toward the mystery and purpose of living. Today I have returned to this origin, to the fleeting inspiration of that time – though now with a more defined and recognizable attitude towards Creation – to make a cycle of paintings of the soul.

The steps I took at that time still help to illuminate the mystery, help me to see things in their deep and dark transparency. Things which back then, though already firmly anchored in my soul, were invisible to me. Today it seems as if this initial drawing actually petrified and waited for its revival. In time I will draw a whole cycle from the variations on the main drawing, the “cosmic egg” and the old trees. *

When my father saw these drawings he was visibly excited. This was quite unusual for him since he was ordinarily able to control his emotions in the most difficult situations. He showed the drawings to several painters and all offered friendly praise but two were more specific. France Mihelic said I should try to work with a sharper black-and-white contrast and Stane Kregar quickly glanced at them and said to my father: “Only when he uses colors will we be able to see if it makes sense to continue.” My father preferred Kregar’s opinion.

My father liked to use me as a model. I could stand motionless for hours and hours in any pose he chose for me. Because of this facility, he sometimes lent me to his colleagues, especially to sculptors. I very carefully observed my father’s hand: how it first mixed the colors on the palette and then with short strokes colored the silhouettes sketched in charcoal and shaded with gray. Many years later I attended an exhibition of entirely gray pictures with Zoran Didek. Each of them had a tiny color spectrum in the corner. Didek was very excited about the idea: this is it! If you want the painting colored, you already have at your disposal all the colors in the spectrum. But I remembered the miraculous way my father had constructed the relationships between the colors in his work until the painting finally became a living organism. I described that experience to Didek and said that for such a painter it might be much better if he colored the painting itself and put a gray spectrum in the corner. *

Shortly before his death, my father told me why he had painted over some of the paintings for which I had posed. He watched me as he painted. The more he worked at applying the colors, at harmonizing them, the more my regard of him glowed. When he sensed true admiration in my asking if God and eternity weren’t merely a dream in which we plunged ourselves to escape if only for a brief instant the cruelty of our reality. Our commitment to death. The fleeting wonder named life. That’s why I begged God for a sign or a trace of his existence.

The drawing was surrealist. I drew in the middle an image like an angel with outspread wings. The figures around the angel had unusual shapes and were composed in such a way that the whole drawing gave an impression of balance. The scene to me seemed like something that existed beyond order and disorder, beyond good and evil. It was not – despite its appearance, which may have suggested otherwise – an apocalyptic vision of the end of all that existed. I felt the drawing was the first step toward the mystery and purpose of living. Today I have returned to this origin, to the fleeting inspiration of that time – though now with a more defined and recognizable attitude towards Creation – to make a cycle of paintings of the soul.

The steps I took at that time still help to illuminate the mystery, help me to see things in their deep and dark transparency. Things which back then, though already firmly anchored in my soul, were invisible to me. Today it seems as if this initial drawing actually petrified and waited for its revival. In time I will draw a whole cycle from the variations on the main drawing, the “cosmic egg” and the old trees. *

When my father saw these drawings he was visibly excited. This was quite unusual for him since he was ordinarily able to control his emotions in the most difficult situations. He showed the drawings to several painters and all offered friendly praise but two were more specific. France Mihelic said I should try to work with a sharper black-and-white contrast and Stane Kregar quickly glanced at them and said to my father: “Only when he uses colors will we be able to see if it makes sense to continue.” My father preferred Kregar’s opinion.

My father liked to use me as a model. I could stand motionless for hours and hours in any pose he chose for me. Because of this facility, he sometimes lent me to his colleagues, especially to sculptors. I very carefully observed my father’s hand: how it first mixed the colors on the palette and then with short strokes colored the silhouettes sketched in charcoal and shaded with gray. Many years later I attended an exhibition of entirely gray pictures with Zoran Didek. Each of them had a tiny color spectrum in the corner. Didek was very excited about the idea: this is it! If you want the painting colored, you already have at your disposal all the colors in the spectrum. But I remembered the miraculous way my father had constructed the relationships between the colors in his work until the painting finally became a living organism. I described that experience to Didek and said that for such a painter it might be much better if he colored the painting itself and put a gray spectrum in the corner. *

Shortly before his death, my father told me why he had painted over some of the paintings for which I had posed. He watched me as he painted. The more he worked at applying the colors, at harmonizing them, the more my regard of him glowed. When he sensed true admiration in my eyes, the painting was finished. If, however, I looked indifferently at the painting and even bored, he pretended to finish it but would keep touching it up. That happened at my last sitting. My father looked at me almost desperately and then suddenly his face lit up because, beside my portrait, he had painted three masks. Thus his remarkable Boy with Masques was born. I never said one word to my father about his paintings and he never showed any interest in my opinion.

Watching my father paint, I also learned how to look at paintings and at the reproductions of sculptors. I came to understand Leonardo da Vinci’s fear of epigones. Each painter has his world, his brush strokes, and his harmony of color and composition. He knew all too well that those who lacked this would take it from others – from the very best if possible. This is a frightful notion particularly for an artist who does not produce miles and miles of paintings and so dedicates a great deal of time, energy, inspiration, vision and symmetry to each individual work, as if each one were his last. But no epigone can imitate or copy the energy brought by a genius to his own work. That’s why certain paintings possess a glow. Even works that are monochromatic can emit a power and force that overwhelms the viewer and fills him with positive energy. Rational artifacts don’t as a rule contain this kind of power. My father had not only the most famous artists in his extraordinarily rich collection of books and artistic reproductions, he also kept reproductions of unknown and forgotten painters. He respected the work of each and every one of them and used to say that you can learn a lot even from the least important painter. If nothing else, you can learn that an epigone never feels or understands the depth and vision of what he imitates. If he could he would create his own method of painting and not utilize mere craft to draw fame and money because of the apparent similarity to the work of great artists. That’s why such paintings wither after a period of time like cut flowers.

And so I became acquainted with a large number of painters almost all of whom had gone on their own stations of the cross until they found an expression either in their own heart or in someone else’s. That’s why I knew it would be much more difficult to put color to an image than it had been to draw it in the first place. My world was filled with all colors though I lived in a state of black and (red and white) and gray to which I was certainly not indifferent. In 1957, I organized with Peter Bozic the first protest demonstration in the socialist-realist state. It took place in the central theatre from which Joze Javorsek’s play, The Magnifying Glass, had been banned for politicalideological reasons. *

But it was only when I met and spent time with Anka, my future wife, that I discovered the main reason for colors and their mystery. Indeed, my painting only really began after I met her. Only then did I become aware of the uniqueness and wonder of the individual personality and of love. Today I know that love is the great and divine grace that gives man power, gives him the sense of truth and the awareness that other people exist.

My drawings remained drawings whether I colored them with water colors, pastels or oils. Father was not very happy but he said nothing. Then I started to simplify individual complicated shapes until they became unrecognizable – total abstractions. Later I would harmonize these abstract shapes with colors until they were finished compositions. But at the time – despite the beauty of the colors and the harmonies (and the disharmonies) in the paintings – I seemed to be on the path toward perfectionism, repetitiveness and ultimately dependence on others, on those who see and feel more strongly and clearly into the depth of the transparent truth. Father agreed with that: he said that he was happy I saw painting as poetics and not as self-sufficiency. And what then? I’d have to decide things for myself, make my work my own and only then could he advise me on finished paintings. He sa,,! me as an epic artist and suggested that I first establish an epic vision. But he knew me and knew that I would work obsessively on anything that puzzled me, that I would persist. *

For a long time, I had been concerned about the “cavity radiation” of colors. It is the most perfect kind of emanation that exists. No color is missing and every color appears in its utmost intensity. “Total radiators” (black bodies) also approach this perfection. Indeed, Planck discovered the foundation of quantum theory and Einstein, so-called Einstein’s law, precisely on the basis of their study of the “cavity radiation” of colors.

For me, color seemed to have totally different characteristics on paintings I knew from before. I stumbled on a partial solution to my problem when I found, in the old warehouse of a printing house where I worked, a pre-war consignment of liquid aniline colors and old paper. The director of the printing house, Bruno Gee, generously gave me some of the aniline colors as well as a thick ream of paper that had been left lying there.

Aniline colors have an extraordinary ability to combine and create nuances of different tones. Because they are pigment, they glow with a greater intensity than other paints.

I had never been able, with diluted oils or water-based paints, to pour the color, to decant it into strong harmonies. Aniline colors, on the other hand, poured and mixed easily, created whole new worlds of tone I had never seen before. Only my satisfaction dictated when to halt the emerging color harmony and I stopped the moment the surface of the color shone up at me.*

I pressed a sponge or newspaper coated and permeated with other paint into the spilt aniline colors. Thus I created shapes and unusual compositions on a color base. It was impossible to repeat any of these images. Each one had a different nuance and was overlaid with figures that mingled differently with the base. There were two reasons for that: I diluted the paint with xylene which dried very quickly and, more importantly, while I was working I subconsciously switched off reason and surrendered to the colors and shapes, to the primary aesthetic sense. If I wanted to keep an especially successful composition, I produced a simple daub and burnt all the pictures with which I wasn’t satisfied. Such selection directed me toward a distinctive creative approach and enabled me to relax into my subconscious mind, letting my reason flow into total openness. I yielded to sheer feeling in these randomly nuanced color compositions. Yet the figures which I applied to the colored background were shaped in contrasting colors in a more and more controlled way. Only when I achieved a certain harmony and mastered the procedure did I begin to harmonize abstraction, to once again find the slightly surrealist shapes I had discovered at the beginning. The colored background and the different colored shapes combined and pressed against each other. And so these paintings contained a touch of the incomprehensible cosmic dimension, a touch of mystery.

Father was so enthusiastic about the iridescence that came through the paper and paints I showed him that he made a series of abstract paintings/pourings. Although we used the same colors and the same paper, my father’s compositions were totally different, had entirely different nuances. They were in some ways obscure as if he had seen his fate and his actual environment which are almost always the same thing. This voyage into the abstract served to cure my father of his own personal abstraction and directed him back to the concreteness of the life we lived in the totalitarian state. He dedicated the last period of his painting to the expression of his critical attitude to this reality. He achieved during this last period of creativity the power and truth of the family paintings of his youth. In these later paintings, he added to the love and intimacy of the earlier ones the horror and hopelessness of the lyric poet. They gave the impression of a lyric poet being crushed by the mill of revolutionary changes, by a world where repressive power, materialist doctrine, money and violence had begun to prevail over the free intellect. When he died, he joined all the disowned, the contemptuously erased artists who have allowed us or one day will allow us a sunny morning in their presence. These remnants of our dear ancestors, despite the miscomprehension and dire straits in which they lived and created, prove to us that life can only be fulfilled if you live it in accordance with your conscience and with love. Love even towards those whose selfishness and greed pollute their people and their nation until they finally disappear into the void of history. In “the badly thrown dice” of their existence.

The method with which I made my last abstract paintings was, as far as my ability allowed, so perfected that I could produce them routinely. I painted the last one in 1963. For a while, I continued to use this method with other materials like canvas and wood panels.

I found it impossible to control paints on large surfaces and on smaller surfaces, the tones never attained the glow of the spilt aniline colors on paper. I knew that my effort to paint larger surfaces would be in vain so I started to paint with oils and brushes. In that year and in the next one, I started to paint large compositions similar to altar paintings. These surrealist pictures were like a kind of altar painting with divisions surrounded by smaller pictures which in traditional Christian altars usually depict the legend or story of a saint through individual scenes. But instead of divine figures I used the abstract figures with which I had the most success in those years.

In the autumn of 1964, my friend, Taras Kermauner, and I went to my little valley in the mountains. A violent storm raged as we climbed up to the valley. It thundered and crashed late into the night. Quite wet, we set up a shelter from the rain and when the storm finally abated we crept out of the shelter. Despite the clouds, the clearing was softly lit with an unusual bluish light. A strange scene seemed to be imprinted on the clouds: the church with its belfry and nave and the linden tree behind the presbytery all lit or rather outlined by a bluish helium light. This bluish halo pouring on to the clouds and on to the phantom church was so extraordinary, so cosmic, that we could only stand before it, speechless and astonished. The scene slowly darkened and faded and the rain began to fall again. The lightening and thunder lasted until dawn. In the morning, Taras concluded that what we had witnessed was very probably the church being struck by lightning and the lightning rod being illuminated by electricity. Hence the glimmering edge of light around the church and the linden tree. Then he went on a walk on the surrounding hills to see the church from a more elevated spot. One can see nothing at all from the little valley itself – not the mountains, not the valley, not the marshlands of Barje. Not even in autumn when all the leaves have fallen from the trees.